Teotihuacan

[14] This suggests that, in the Maya civilization of the Classic period, Teotihuacan was understood as a Place of Reeds similar to other Postclassic Central Mexican settlements that took the name of Tollan, such as Tula-Hidalgo and Cholula.

In the Mesoamerican concept of urbanism, Tollan and other language equivalents serve as a metaphor, linking the bundles of reeds and rushes that formed part of the lacustrine environment of the Valley of Mexico and the large gathering of people in a city.

[18][20] Around 300 CE, the Temple of the Feathered Serpent was desecrated and construction in the city proceeded in a more egalitarian direction, focusing on the building of comfortable, stone accommodations for the population.

[23] Factors that also led to the decline of the city included disruptions in tributary relations, increased social stratification, and power struggles between the ruling and intermediary elites.

Contemporaneous cities in the same region, including Mayan and Zapotec, as well as the earlier Olmec civilization, left ample attestations of dynastic authoritarian sovereignty in the form of royal palaces, ceremonial ball courts, and depictions of war, conquest, and humiliated captives.

The Feathered-Serpent Pyramid was burnt, all the sculptures were torn from the temple, and another platform was built to efface the facade ...[30]In 426, the Copán ruling dynasty was created with K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' as the first king.

Variants of the generic style are found in a number of Maya region sites including Tikal, Kaminaljuyu, Copan, Becan, and Oxkintok, and particularly in the Petén Basin and the central Guatemalan highlands.

[42] Some think this suggests that the burning was from an internal uprising and the invasion theory is flawed because early archeological efforts were focused exclusively on the palaces and temples, places used by the upper classes.

[49] The eruption of Popocatepetl in the middle of the first century preceded that of Xitle, and is believed to have begun the aforementioned degradation of agricultural lands and structural damage to the city.

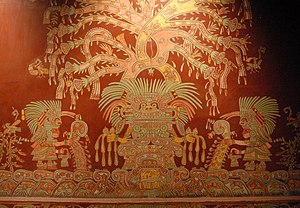

Thematic elements of these murals included processions of lavishly dressed priests, jaguar figures, the storm god deity, and an anonymous goddess whose hands offer gifts of maize, precious stones, and water.

[59] Along with archeological evidence pointing to one of the primary traded items being textiles, craftspeople capitalized on their mastery of painting, building, the performance of music and military training.

Animals that were considered sacred and represented mythical powers and the military were also buried alive or captured and held in cages such as cougars, a wolf, eagles, a falcon, an owl, and even venomous snakes.

[9] The oxygen isotope ratio testing was particularly helpful when analyzing this neighborhood because it painted a clear picture of the initial influx from Oaxaca, followed by routine journeys back to the homeland to maintain the culture and heritage of the following generations.

[9] This neighborhood, similarly to Tlailotclan, saw a huge influx of immigration, determined by the strontium isotope ratio testing of bones and teeth, with people spending a significant part of their lives before death in Teotihuacan.

Between April 26 and July 29, 1932, Swedish anthropologist/archaeologist Sigvald Linné, his wife, and a small crew excavated in the Xolalpan area, part of the municipality of San Juan Teotihuacán.

[citation needed] In late 2003 a tunnel beneath the Temple of the Feathered Serpent was accidentally discovered by Sergio Gómez Chávez and Julie Gazzola, archeologists of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH).

[94][95][96][97] First trying to examine the hole with a flashlight from above Gómez could see only darkness, so tied with a line of heavy rope around his waist he was lowered by several colleagues, and descending into the murk he realized it was a perfectly cylindrical shaft.

[94] Before the start of excavations, beginning in the early months of 2004, Victor Manuel Velasco Herrera, from UNAM Institute of Geophysics, determined with the help of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and a team of some 20 archeologists and workers the approximate length of the tunnel and the presence of internal chambers.

The archeologists explored the tunnel with a remote-controlled robot called Tlaloc II-TC, equipped with an infrared camera and a laser scanner that generates 3D visualization to perform three-dimensional register of the spaces beneath the temple.

In August 2010 Gómez Chávez, now director of Tlalocan Project: Underground Road, announced that INAH's investigation of the tunnel – closed nearly 1,800 years ago by Teotihuacan dwellers – will proceed.

The rich array of objects unearthed included: wooden masks covered with inlaid rock jade and quartz, elaborate necklaces, rings, greenstone crocodile teeth and human figurines, crystals shaped into eyes, beetle wings arranged in a box, sculptures of jaguars, and hundreds of metalized spheres.

[95][96][102] The walls and ceiling of the tunnel were found to have been carefully impregnated with mineral powder composed of magnetite, pyrite (fool's gold), and hematite to provide a glittering brightness to the complex, and to create the effect of standing under the stars as a peculiar re-creation of the underworld.

[101] At the end of the passage, Gómez Chávez's team uncovered four greenstone statues, wearing garments and beads; their open eyes would have shone with precious minerals.

Two of the figurines were still in their original positions, leaning back and appearing to contemplate up at the axis where the three planes of the universe meet – likely the founding shamans of Teotihuacan, guiding pilgrims to the sanctuary, and carrying bundles of sacred objects used to perform rituals, including pendants and pyrite mirrors, which were perceived as portals to other realms.

The size and quality of the monuments, the originality of the residential architecture, and the miraculous iconography in the colored murals of the buildings or the vases with the paintings of butterflies, eagles, coyotes with feathers and jaguars, suggest beyond any doubt a high-level civilization, whose cultural influences were spread and transplanted into all the Mesoamerican populations.

The main monuments of the city of Teotihuacan are connected to each other by a central road of 45 meters wide and a length of 2 kilometers, called "Avenue of the Dead " (Avenida de Los Muertos), because it is believed to have been paved with tombs.

Furthermore, the Sun Pyramid is aligned to Cerro Gordo to the north, which means that it was purposefully built on a spot where a structure with a rectangular ground plan could satisfy both topographic and astronomical requirements.

According to Sergio Gómez Chávez, an archeologist and researcher for Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) fragments of ancient pottery were found where trucks dumped the soil from the site.

The National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) had suspended authorization for those projects in March, yet construction work with heavy machinery and looting of artifacts had continued.

The seizure of the land came a week after the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) warned that Teotihuacán was at risk of losing its UNESCO World Heritage designation.