Mesoamerican ballgame

[citation needed] In the most common theory of the game, the players struck the ball with their hips, although some versions allowed the use of forearms, rackets, bats, or handstones.

The ball was made of solid rubber and weighed as much as 9 lbs (4 kg), and sizes differed greatly over time or according to the version played.

[4] Pre-Columbian ballcourts have been found throughout Mesoamerica, as for example at Copán, as far south as modern Nicaragua, and possibly as far north as what is now the U.S. state of Arizona.

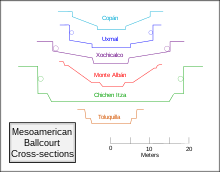

[5] These ballcourts vary considerably in size, but all have long narrow alleys with slanted side-walls or vertical walls against which the balls could bounce.

This term originates from a 1932 article by Danish archaeologist Frans Blom, who adapted it from the Yucatec Maya word pokolpok.

[11] Here, at Paso de la Amada, archaeologists have found the oldest ballcourt yet discovered, dated to approximately 1400 BC.

[14] The earliest-known rubber balls in the world come from the sacrificial bog at El Manatí, an early Olmec-associated site located in the hinterland of the Coatzacoalcos River drainage system.

[17][18] A stone "yoke" of the type frequently associated with Mesoamerican ballcourts was also reported to have been found by local villagers at the site, leaving open the distinct possibility that these rubber balls were related to the ritual ballgame, and not simply an independent form of sacrificial offering.

[19][20] Excavations at the nearby Olmec site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán have also uncovered a number of ballplayer figurines, radiocarbon-dated as far back as 1250–1150 BC.

[27][28] Some games were played on makeshift courts for simple recreation while others were formal spectacles on huge stone ballcourts leading to human sacrifice.

In the Postclassic period, the Maya began placing vertical stone rings on each side of the court, the object being to pass the ball through one, an innovation that continued into the later Toltec and Aztec cultures.

Capes and masks, for example, are shown on several Dainzú reliefs, while Teotihuacan murals show men playing stick-ball in skirts.

Loincloths are found on the earliest ballplayer figurines from Tlatilco, Tlapacoya, and the Olmec culture, are seen in the Weiditz drawing from 1528 (below), and, with hip guards, are the sole outfit of contemporary ulama players (above)—a span of nearly 3,000 years.

Gloves appear on the purported ballplayer reliefs of Dainzú, roughly 500 BC, as well as the Aztec players are drawn by Weiditz 2,000 years later (see drawing below).

While several dozen ancient balls have been recovered, they were originally laid down as offerings in a sacrificial bog or spring, and there is no evidence that any of these were used in the ballgame.

[45] All ballcourts have the same general shape, a long narrow playing alley flanked by walls with both horizontal and sloping (or, more rarely, vertical) surfaces.

[51] Ancient cities with particularly fine ballcourts in good condition include Tikal, Yaxha, Copán, Coba, Iximche, Monte Albán, Uxmal, Chichen Itza, Yagul, Xochicalco, Mixco Viejo, and Zaculeu.

Ballcourts were public spaces used for a variety of elite cultural events and ritual activities like musical performances and festivals, and, of course, the ballgame.

Pictorial depictions often show musicians playing at ballgames, and votive deposits buried at the Main Ballcourt at Tenochtitlan contained miniature whistles, ocarinas, and drums.

[54] These examples and others are cited by many researchers who have made compelling arguments that the game served as a way to defuse or resolve conflicts without genuine warfare, to settle disputes through a ballgame instead of a battle.

[58][59] Other scholars support these arguments by pointing to the warfare imagery often found at ballcourts: The association between human sacrifice and the ballgame appears rather late in the archaeological record, no earlier than the Classic era.

[65] Rather than nearly nude and sometimes battered captives, the ballcourts at El Tajín and Chichen Itza show the sacrifice of practiced ballplayers, perhaps the captain of a team.

[66][67] Decapitation is particularly associated with the ballgame—severed heads are featured in much Late Classic ballgame art and appear repeatedly in the Popol Vuh.

According to an important Nahua source, the Leyenda de los Soles,[72] the Toltec king Huemac played ball against the Tlalocs, with precious stones and quetzal feathers at stake.

The ballcourt markers along the centerline of the Classic playing field depicted ritual and mythical scenes of the ballgame, often bordered by a quatrefoil that marked a portal into another world.

[77] The Aztec version of the ballgame is called ōllamalitzli (sometimes spelled ullamaliztli)[78] and are derived from the word ōlli "rubber" and the verb ōllama or "to play ball".

The Codex Mendoza gives a figure of 16,000 lumps of raw rubber being imported to Tenochtitlan from the southern provinces every six months, although not all of it was used for making balls.

In 1528, soon after the Spanish conquest, Cortés sent a troupe of ōllamanime (ballplayers) to Spain to perform for Charles V where they were drawn by the German Christoph Weiditz.

[84][85] Batey, a ball game played on many Caribbean islands in the West Indies, has been proposed as a descendant of the Mesoamerican ballgame, perhaps through the Maya.

-shape ball court in

Cihuatán

site,

El Salvador

-shape ball court in

Cihuatán

site,

El Salvador