Ancient Near Eastern cosmology

However, a number of lines of evidence, including descriptions from the cosmological texts themselves, presumptions of this cosmography in non-cosmological texts (like incantations), anthropological studies of contemporary primitive cosmologies, and cognitive expectations that humans construct mental models to explain observation, support that the ancient near eastern cosmography was not phenomenological.

[41] Mythical bonds, akin to ropes or cables, played the role of cohesively holding the entire world and all its layers of heaven and Earth together.

[43] The finite nature of the cosmos was also suggested to the ancients by the periodic and regular movements of the heavenly bodies in the visible vicinity of the Earth.

[56] The fourth model was a flat (or slightly convex) celestial plane which, depending on the text, was thought to be supported in various ways: by pillars, staves, scepters, or mountains at the extreme ends of the Earth.

[60] In the Babylonian Map, the world continent is surrounded by a bitter salt-water Ocean (called marratu, or "salt-sea")[61] akin to Oceanus described by the poetry of Homer and Hesiod in early Greek cosmology, as well as the statement in the Bilingual Creation of the World by Marduk that Marduk created the first dry land surrounded by a cosmic sea.

[66] According to iconographic and literary evidence, the cosmic mountain, known as Mashu in the Epic of Gilgamesh, was thought to be located at or extend to both the westernmost and easternmost points of the earth, where the sun could rise and set respectively.

"[38] In the Baal Cycle, two cosmic mountains exist at the horizon acting as the point through which the sun rises from and sets into the underworld (Mot).

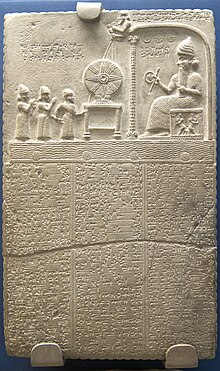

In the 2nd millennium BC, Mesopotamian scholars composed the Enūma Anu Enlil, a collection of at least seventy tablets concerned with omens.

[86] Mesopotamian cosmology would differ from the practice of astronomy in terms of terminology: for astronomers, the word "firmament" was not used but instead "sky" to describe the domain in which the heavenly affairs were visible.

A Sumerian inscription of Kudur-Mabuk, for example, reads "The reliable god, who interchanges day and night, who establishes the month, and keeps the year intact."

By the 3rd millennium BC, the planet Venus was identified as the astral form of the goddess Inanna (or Ishtar), and motifs such as the morning and evening star were applied to her.

The most obvious characteristic of the stars were their luminosity and their study for the purposes of divination, solving calendrical calculations, and predictions of the appearances of planets, led to the discovery of their periodic motion.

[107] The core Mesopotamian myth to explain the gods' origins begins with the primeval ocean, personified by Nammu, containing Father Sky and Mother Earth within her.

The conception of Nammu as mother of Sky-Earth is first attested in the Ur III period (early 2nd millennium BC), though it may go back to an earlier Akkadian era.

[120] Biblical references to stretching the heavens typically occur in conjunction with statements that God made or laid the foundations of the earth.

[129] Cosmogonic prologues preface texts falling in the genre of the Sumerian and Akkadian disputation poems,[130] as well as individual works like the Song of the hoe, Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, and Lugalbanda I.

[131] The Enuma Elish is the most famous Mesopotamian creation story and was widely known in among learned circles across Mesopotamia, influencing both art and ritual.

Marduk forms the heavenly bodies including the sun, moon, and stars to produce periodic astral activity that is the basis for the calendar, before finally setting up the cosmic capital at Babylon.

[149] In 1895, Hermann Gunkel related this narrative to the Enuma Elish via an etymological relationship between Tiamat and təhôm ("the deep" or "the abyss") and a sharing of the Chaoskampf motif.

In addition, the Genesis cosmogony differs by describing the separation of the upper and lower waters by the creation of a firmament, whereas here, they are typically assembled into clouds.

The first book of the Babyloniaca of the Babylonian priest Berossus, composed in the third century BC, offers a variant (or, perhaps, an interpretation) of the cosmogony of the Enuma Elish.

Unlike in the Enuma Elish, where sea monsters are generated for combat with other gods, in Berossus' account, they emerge by spontaneous generation and are described in a different manner to the 11 monsters of the Enuma Elish, as it expands beyond the purely mythical creatures of that account in a potential case of influence from Greek zoology.

When Belos saw the land empty and barren, he ordered one of the gods to cut off his own head and to mix the blood that flowed out with earth and to form men and wild animals that were capable of enduring the air.

One Hellenistic-era Babylonian priest, Berossus, wrote a Greek text about Mesopotamian traditions called the Babyloniaca (History of Babylon).

The creation account of Berossus is attributed to the divine messenger Oannes in the period after the global flood and is derivative of the Enuma Elish but also has significant variants to it.

[165] Many believe that a Hurro-Hittite work from the 13th century BC, the Song of Emergence (CTH 344), was directly used by Hesiod on the basis of extensive similarities between their accounts.

In light of evidence which has emerged in recent decades, the present view is that this idea entered into Zoroastrian thought through Mesopotamian channels of influence.

A genre of literature emerged among Jews and Christians dedicated to the composition of texts commenting precisely on this narrative to understand the cosmos and its origins: these works are called Hexaemeron.

Philo preferred an allegorical form of exegesis, in line with that of the School of Alexandria, and so was partial to a Hellenistic cosmology as opposed to an ancient near eastern one.

Instead, work in the field of Quranic studies has identified the primary historical context for the reception of these ideas to have been in the Christian and Jewish cosmologies of late antiquity.