Gilgamesh

The standard Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh was composed by a scribe named Sîn-lēqi-unninni, probably during the Middle Babylonian Period (c. 1600 – c. 1155 BC), based on much older source material.

After Enkidu dies of a disease sent as punishment from the gods, Gilgamesh becomes afraid of his own death and visits the sage Utnapishtim, the survivor of the Great Flood, hoping to find immortality.

[citation needed] The story of Gilgamesh's birth is described in an anecdote in On the Nature of Animals by the Greek writer Aelian (2nd century AD).

[17][18] Stephanie Dalley, a scholar of the ancient Near East, states that "precise dates cannot be given for the lifetime of Gilgamesh, but they are generally agreed to lie between 2800 and 2500 BC".

[18] An inscription, possibly belonging to a contemporary official under Gilgamesh, was discovered in the archaic texts at Ur;[21] his name reads: "Gilgameš is the one whom Utu has selected".

[22] Lines eleven through fifteen of the inscription read: For a second time, the Tummal fell into ruin, Gilgamesh built the Numunburra of the House of Enlil.

[22] Fragments of an epic text found in Mê-Turan (modern Tell Haddad) relate that upon his death Gilgamesh was buried under the river bed,[22] and the workmen of Uruk temporarily diverted the flow of the Euphrates for this purpose.

[22] Over the centuries, there may have been a gradual accretion of stories about Gilgamesh, some possibly derived from the real lives of other historical figures, such as Gudea, the Second Dynasty ruler of Lagash (2144–2124 BC).

[17] The most complete surviving version of the Epic of Gilgamesh is recorded on a set of twelve clay tablets dating to the seventh century BC, found in the Library of Ashurbanipal in the Assyrian capital of Nineveh,[17][22][50] with many pieces missing or damaged.

[17][22][50] Some scholars and translators choose to supplement the missing parts with material from the earlier Sumerian poems or from other versions of the epic found at other sites throughout the Near East.

[47][61] The journey to Utnapishtim involves a series of episodic challenges, which probably originated as major independent adventures,[61] but, in the epic, they are reduced to what Joseph Eddy Fontenrose calls "fairly harmless incidents".

[47][32][62] In it, Gilgamesh sees a vision of Enkidu's ghost, who promises to recover the lost items[47][37] and describes to his friend the abysmal condition of the Underworld.

[68][65][69][70] According to classics scholar Barry B. Powell, early Greeks were probably exposed to and influenced by Mesopotamian oral traditions through their extensive connections to the civilizations of the ancient Near East.

[71] In this scene, Aphrodite, the Greek analogue of Ishtar, is wounded by the hero Diomedes and flees to Mount Olympus, where she cries to her mother Dione and is mildly rebuked by her father Zeus.

[65] Both heroes visit the Underworld[72] and both find themselves unhappy while living in an otherworldly paradise in the company of a seductive sorceress: Siduri (for Gilgamesh) and Calypso (for Odysseus).

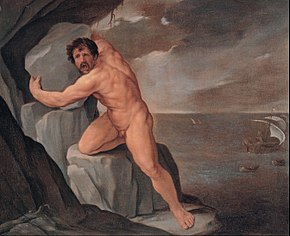

[74] The story of Gilgamesh's birth is not recorded in any extant Sumerian or Akkadian text,[64] but a version of it is described in De Natura Animalium (On the Nature of Animals) 12.21, a commonplace book written in Greek around 200 AD by the Hellenized Roman orator Aelian.

[22][50][28]: 95 Layard was seeking evidence to confirm the historicity of the events described in the Hebrew Bible, i.e. the Christian Old Testament,[22] which was believed to contain the oldest texts in the world.

[22] The first translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh was produced in the early 1870s by George Smith, a scholar at the British Museum,[79][81][82] who published the Flood story from Tablet XI in 1880 under the title The Chaldean Account of Genesis.

[85] Most attention towards the Epic of Gilgamesh in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came from German-speaking countries,[86] where controversy raged over the relationship between Babel und Bibel ("Babylon and Bible").

[87] In January 1902, the German Assyriologist Friedrich Delitzsch gave a lecture at the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin before the Kaiser and his wife, in which he argued that the Flood story in the Book of Genesis was directly copied from the Epic of Gilgamesh.

[90] Significantly influenced by Edward FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and Edwin Arnold's The Light of Asia,[90] Hamilton's characters dress more like nineteenth-century Turks than ancient Babylonians.

[91] Hamilton also changed the tone of the epic from the "grim realism" and "ironic tragedy" of the original to a "cheery optimism" filled with "the sweet strains of love and harmony".

[96] The Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, drawing on the theories of James George Frazer and Paul Ehrenreich, interpreted Gilgamesh and Eabani (the earlier misreading for Enkidu) as representing "man" and "crude sensuality" respectively.

[82] In his 1947 existentialist novel Die Stadt hinter dem Strom, the German novelist Hermann Kasack adapted elements of the epic into a metaphor for the aftermath of the destruction of World War II in Germany,[82] portraying the bombed-out city of Hamburg as resembling the frightening Underworld seen by Enkidu in his dream.

[82] In the United States, Charles Olson praised the epic in his poems and essays[82] and Gregory Corso believed that it contained ancient virtues capable of curing what he viewed as modern moral degeneracy.

[82] The 1966 postfigurative novel Gilgamesch by Guido Bachmann became a classic of German "queer literature"[82] and set a decades-long international literary trend of portraying Gilgamesh and Enkidu as homosexual lovers.

[82] As the Green Movement expanded in Europe, Gilgamesh's story began to be seen through an environmentalist lens,[82] with Enkidu's death symbolizing man's separation from nature.

[106][82] The Great American Novel (1973) by Philip Roth features a character named "Gil Gamesh",[106] who is the star pitcher of a fictional 1930s baseball team called the "Patriot League".

[107] Saddam's first novel Zabibah and the King (2000) is an allegory for the Gulf War set in ancient Assyria that blends elements of the Epic of Gilgamesh and the One Thousand and One Nights.

[108] Like Gilgamesh, the king at the beginning of the novel is a brutal tyrant who misuses his power and oppresses his people,[109] but, through the aid of a commoner woman named Zabibah, he grows into a more just ruler.