History of Mesopotamia

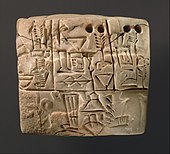

This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing in the late 4th millennium BC, an increasing amount of historical sources.

The name was presumably translated from a term already current in the area—probably in Aramaic—and apparently was understood to mean the land lying "between the (Euphrates and Tigris) rivers", now Iraq.

[2][3][4][5][6][7] The neighbouring steppes to the west of the Euphrates and the western part of the Zagros Mountains are also often included under the wider term Mesopotamia.

By combining absolute and relative dating methods, a chronological framework has been built for Mesopotamia that still incorporates many uncertainties but that also continues to be refined.

[22][nb 2] The early Neolithic human occupation of Mesopotamia is, like the previous Epipaleolithic period, confined to the foothill zones of the Taurus and Zagros Mountains and the upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys.

[23][24] The so-far earliest monumental sculptures and circular stone buildings from Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey date to the PPNA/Early PPNB and represent, according to the excavator, the communal efforts of a large community of hunter-gatherers.

[25][26] The Fertile Crescent was inhabited by several distinct, flourishing cultures between the end of the last ice age (c. 10,000 BC) and the beginning of history.

One of the oldest known Neolithic sites in Mesopotamia is Jarmo, settled around 7000 BC and broadly contemporary with Jericho (in the Levant) and Çatalhöyük (in Anatolia).

Pottery was decorated with abstract geometric patterns and ornaments, especially in the Halaf culture, also known for its clay fertility figurines, painted with lines.

The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid in Southern Mesopotamia, where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

The homogeneity of the Jemdet Nasr period across a large area of southern Mesopotamia indicates intensive contacts and trade between settlements.

This is strengthened by the find of a sealing at Jemdet Nasr that lists a number of cities that can be identified, including Ur, Uruk and Larsa.

[43] The Sumerians were firmly established in Mesopotamia by the middle of the 4th millennium BC, in the archaeological Uruk period, although scholars dispute when they arrived.

Their mythology includes many references to the area of Mesopotamia but little clue regarding their place of origin, perhaps indicating that they had been there for a long time.

In the past, the Sumerian King List was considered to be an important historical source, but recent scholarship has dismissed the utility of this text up to the point that it should not be used at all for the reconstruction of Early Dynastic political history.

Some time later, Lugal-Anne-Mundu of Adab created the first, if short-lived, empire to extend west of Mesopotamia, at least according to historical accounts dated centuries later.

The Akkadians further developed the Sumerian irrigation system with the incorporation of large weirs and diversion dams into the design to facilitate the reservoirs and canals required to transport water vast distances.

An Assyrian king named Ilushuma (1945–1906 BC) became a dominant figure in Mesopotamia, raiding the southern city states and founding colonies in Asia Minor.

After the death of Hammurabi, the first Babylonian dynasty lasted for another century and a half, but his empire quickly unravelled, and Babylon once more became a small state.

Shamshi-Adad I created a regional empire in Assyria, maintaining and expanding the established colonies in Asia Minor and Syria.

The nation remained relatively strong and stable, peace was made with the Kassite rulers of Babylonia, and Assyria was free from Hittite, Hurrian, Gutian, Elamite and Mitanni threat.

This was ended by Eriba-Adad I (1392 BC - 1366), and his successor Ashur-uballit I completely overthrew the Mitanni Empire and founded a powerful Assyrian Empire that came to dominate Mesopotamia and much of the ancient Near East (including Babylonia, Asia Minor, Iran, the Levant and parts of the Caucasus and Arabia), with Assyrian armies campaigning from the Mediterranean Sea to the Caspian, and from the Caucasus to Arabia.

During this period Assyria became a major power, overthrowing the Mitanni Empire, annexing swathes of Hittite, Hurrian and Amorite land, sacking and dominating Babylon, Canaan/Phoenicia and becoming a rival to Egypt.

Assyria participated in these wars toward the end of the period, overthrowing the Mitanni Empire and besting the Hittites and Phrygians, but the Kassites in Babylon did not.

By 1450 BC they established a medium-sized empire under a Mitanni ruling class, and temporarily made tributary vassals out of kings in the west, making them a major threat for the Pharaoh in Egypt until their overthrow by Assyria.

By 1300 BC the Hurrians had been reduced to their homelands in Asia Minor after their power was broken by the Assyrians and Hittites, and held the status of vassals to the "Hatti", the Hittites, a western Indo-European people (belonging to the linguistic "centum" group) who dominated most of Asia Minor (modern Turkey) at this time from their capital of Hattusa.

Records from the 12th and 11th centuries BC are sparse in Babylonia, which had been overrun with new Semitic settlers, namely the Arameans, Chaldeans and Sutu.

At its height Assyria conquered the 25th Dynasty Egypt (and expelled its Nubian/Kushite dynasty) as well as Babylonia, Chaldea, Elam, Media, Persia, Urartu, Phoenicia, Aramea/Syria, Phrygia, the Neo-Hittites, Hurrians, northern Arabia, Gutium, Israel, Judah, Moab, Edom, Corduene, Cilicia, Mannea and parts of Ancient Greece (such as Cyprus), and defeated and/or exacted tribute from Scythia, Cimmeria, Lydia, Nubia, Ethiopia and others.

After the death of Ashurbanipal in 627 BC, the Assyrian empire descended into a series of bitter civil wars, allowing its former vassals to free themselves.

The city of Assur was still occupied until the 14th century, and Assyrians possibly still formed the majority in northern Mesopotamia until the Middle Ages.