Meteor

A meteor, known colloquially as a shooting star, is a glowing streak of a small body (usually meteoroid) going through Earth's atmosphere, after being heated to incandescence by collisions with air molecules in the upper atmosphere,[2][3][4] creating a streak of light via its rapid motion and sometimes also by shedding glowing material in its wake.

Meteoroid sizes can be calculated from their mass and density which, in turn, can be estimated from the observed meteor trajectory in the upper atmosphere.

Before that, they were seen in the West as an atmospheric phenomenon, like lightning, and were not connected with strange stories of rocks falling from the sky.

In 1807, Yale University chemistry professor Benjamin Silliman investigated a meteorite that fell in Weston, Connecticut.

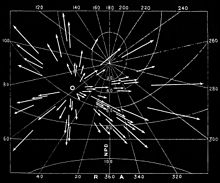

Careful observers noticed that the radiant, as the point is called, moved with the stars, staying in the constellation Leo.

After reviewing historical records, Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers predicted the storm's return in 1867, drawing other astronomers' attention to the phenomenon.

[12] With Giovanni Schiaparelli's success in connecting the Leonids (as they are called) with comet Tempel-Tuttle, the cosmic origin of meteors was firmly established.

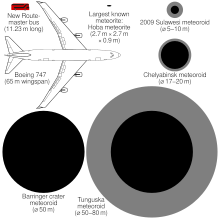

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) defines a fireball as "a meteor brighter than any of the planets" (apparent magnitude −4 or greater).

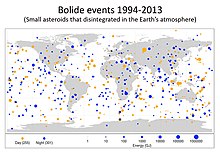

In the late twentieth century, bolide has also come to mean any object that hits Earth and explodes, with no regard to its composition (asteroid or comet).

During the entry of a meteoroid or asteroid into the upper atmosphere, an ionization trail is created, where the air molecules are ionized by the passage of the meteor.

These particles might affect climate, both by scattering electromagnetic radiation and by catalyzing chemical reactions in the upper atmosphere.

The visible light produced by a meteor may take on various hues, depending on the chemical composition of the meteoroid, and the speed of its movement through the atmosphere.

For example, scientists at NASA suggested that the turbulent ionized wake of a meteor interacts with Earth's magnetic field, generating pulses of radio waves.

[35][36][37][38] This proposed mechanism, although proven plausible by laboratory work, remains unsupported by corresponding measurements in the field.

A meteor shower is the result of an interaction between a planet, such as Earth, and streams of debris from a comet or other source.

Some researchers attribute this to an intrinsic variation in the meteoroid population along Earth's orbit, with a peak in big fireball-producing debris around spring and early summer.

Others have pointed out that during this period the ecliptic is (in the northern hemisphere) high in the sky in the late afternoon and early evening.