Mexican peso crisis

The Mexican treasury began issuing short-term debt instruments denominated in domestic currency with a guaranteed repayment in U.S. dollars, attracting foreign investors.

Mexico enjoyed investor confidence and new access to international capital following its signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

However, a violent uprising in the state of Chiapas, as well as the assassination of the presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio, resulted in political instability, causing investors to place an increased risk premium on Mexican assets.

Under election pressures, Mexico purchased its own treasury securities to maintain its money supply and avert rising interest rates, drawing down the bank's dollar reserves.

To discourage the resulting capital flight, the bank raised interest rates, but higher costs of borrowing merely hurt economic growth.

With 1994 being the final year of his administration's sexenio (the country's six-year executive term limit), then-President Carlos Salinas de Gortari endorsed Luis Donaldo Colosio as the Institutional Revolutionary Party's (PRI) presidential candidate for Mexico's 1994 general election.

Investors further questioned Mexico's political uncertainties and stability when PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio was assassinated while campaigning in Tijuana in March 1994, and began setting higher risk premiums on Mexican financial assets.

To discourage such capital flight, particularly from debt instruments, the Mexican central bank raised interest rates, but higher borrowing costs ultimately hindered economic growth prospects.

[2]: 10 Mutual funds, which had invested in over $45 billion worth of Mexican assets in the several years leading up to the crisis, began liquidating their positions in Mexico and other developing countries.

Motivated to deter a potential surge in illegal immigration and to mitigate the spread of investors' lack of confidence in Mexico to other developing countries, the United States coordinated a $50 billion bailout package in January 1995, to be administered by the IMF with support from the G7 and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

The package established loan guarantees for Mexican public debt aimed at alleviating its growing risk premia and boosting investor confidence in its economy.

Some congressional representatives agreed with American economist and former chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, L. William Seidman, that Mexico should just negotiate with creditors without involving the United States, especially in the interest of deterring moral hazard.

On the other hand, supporters of U.S. involvement such as Fed Chair Alan Greenspan argued that the fallout from a Mexican sovereign default would be so devastating that it would far exceed the risks of moral hazard.

[2]: 10–11 Then-U.S. Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin's appropriation of funds from the Exchange Stabilization Fund in support of the Mexican bailout was scrutinized by the United States House Committee on Financial Services, which expressed concern about a potential conflict of interest because Rubin had formerly served as co-chair of the board of directors of Goldman Sachs, which had a substantial share in distributing Mexican stocks and bonds.

Mexico's financial sector bore the brunt of the crisis as banks collapsed, revealing low-quality assets and fraudulent lending practices.

Thousands of mortgages went into default as Mexican citizens struggled to keep pace with rising interest rates, resulting in widespread repossession of houses.

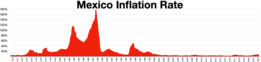

[14][15] In addition to declining GDP growth, Mexico experienced severe inflation and extreme poverty skyrocketed as real wages plummeted and unemployment nearly doubled.

Consumer price inflation and a tightening credit market during the crisis proved challenging for urban workers, while rural households shifted to subsistence agriculture.

[16]: 21–22 Critical scholars contend that the 1994 Mexican peso crisis exposed the problems of Mexico’s neoliberal turn to the Washington consensus approach to development.

Notably, the crisis revealed the problems of a privatized banking sector within a liberalized yet internationally subordinate economy that is dependent on foreign flows of finance capital.