Michael Maestlin

Michael Maestlin (also Mästlin, Möstlin, or Moestlin; 30 September 1550 – 26 October 1631)[1] was a German astronomer and mathematician, best known as the mentor of Johannes Kepler.

[2] Maestlin was born on 30 September 1550 in Göppingen, a small town in southern Germany located about 50 kilometers east of Tübingen.

[4] He explains that one of his ancestors received the nickname after an old blind woman touched him and exclaimed, "Wie bist du doch so mast und feist!

In a letter to Johannes Kepler written that same year, Maestlin shared how deeply troubled he was by the death of his month-old son, August.

[7] Maestlin studied theology at the Tübinger Stift, an elite educational institution founded in 1536 by Duke Ulrich von Württemberg.

[3] After obtaining his master's degree, Maestlin remained at the university as both a theology student and a tutor in the seminary church in Württemberg.

[9] It is believed Apian taught topics such as Frisius's Arithmetic, Euclid's Elements, Proclus's Sphera, Peurbach's Theoricae Novae Planetarus, and the use of geodetic instruments.

[3] Apian’s teachings appear to have influenced Maestlin’s work, particularly his paper on sundials, which includes structured elements of celestial globes and maps.

[citation needed] In 1576, Maestlin was appointed as a deacon at the Lutheran church in Backnang, a town about 30 kilometers northwest of Göppingen.

[3] In 1587, Maestlin published a manuscript titled Tabula Motus Horarii, which provides the daily motion of the Sun in hours and minutes, along with its positions in two-minute intervals.

[12] Although Maestlin primarily taught the traditional geocentric Ptolemaic model of the Solar System, he was one of the earliest proponents of the heliocentric Copernican view and introduced it to his advanced students.

[12] Maestlin frequently corresponded with Kepler and played a significant role in influencing his adoption of the Copernican system.

[15] Maestlin was one of the few astronomers of the 16th century to fully embrace the Copernican hypothesis, which proposed that the Earth was a planet that moved around the Sun.

He argued that unless people concede that comets can exist in the stellar orb, which has an immense altitude and an unknown extent, the distance between the Sun and the Earth, as described by Copernicus, remains incomparable.

[3] Epitome Astonomiae went through six editions and used works such as Ptolemy's famous geocentric model to create detailed descriptions of astronomy.

In a letter to Kepler, Maestlin mentioned that he was unable to observe the satellites of Saturn or the phases of Venus; however, he was able to see the moons of Jupiter.

[18] Maestlin's treatise attracted the attention of Tycho Brahe, who reproduced it in its entirety, along with his own criticisms, in one of the best-known publications on the subject, his posthumously printed Astronomiae instauratae progymnasmata.

[10] When the comet appeared, Maestlin, along with the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, was one of the first to actively calculate its path in a more complex manner than simply tracking its movement across the sky.

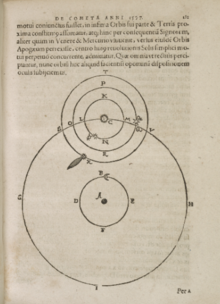

[20] Maestlin also supervised and made significant contributions to the tables and diagrams in Kepler's Mysterium Cosmographicum, published in 1596.

[21] The appendix was titled "On the Dimensions of the Heavenly Circles and Spheres, According to the Prutenic Tables After the Theory of Nicolaus Copernicus" and was intended to address "the needs of a hypothetical educated reader" while answering some of the questions Kepler had raised in the book.

Maestlin provided the geometry to help visualize Kepler's theory of the Sun's force and its effects on the other planets, which was included in Mysterium Cosmographicum.

[23] However, these diagrams caused a misunderstanding that lasted for centuries, as Maestlin did not clarify whether the planets were meant to move along the lines of the circles representing his planetary system or within the spaces he had drawn.

Instead, he began working on a treatise titled Consideratio Astronomica inusitatae Novae et prodigiosae Stellae, superiori 1604 anno, sub initium Octobris, iuxta Eclipticam in signo Sagittarii vesperi exortae, et adhuc nunc eodem loco lumine corusco lucentis (Astronomical Consideration of the Extraordinary and Prodigious New Star that Appeared Near the Ecliptic in the Sign of Sagittarius One Evening in Early October in the Preceding Year 1604, and Continues to Shine in the Same Place with a Tremulous Light).

Kepler argued that failing to comment on this event would make Maestlin guilty of the "crime of deserting astronomy.

This work, written entirely in Latin, was titled Consideratio Astronomica inusitatae Novae et prodigiosae Stellae, superiori 1604 anno, sub initium Octobris, iuxta Eclipticam in signo Sagittarii vesperi exortae, et adhuc nunc eodem loco lumine corusco lucentis (Astronomical consideration of the extraordinary and prodigious new star that appeared near the ecliptic in the sign of Sagittarius one evening in early October in the preceding year 1604, and continues to shine in the same place with a tremulous light).

It is estimated that Maestlin wrote the treatise in April 1605, as he describes the months of February or March when the supernova showed signs of decreasing intensity and brightness.

[2] During the time of Maestlin and Kepler, questioning God's responsibility for creating the world and all the creatures in it could be seen as dangerous, as one might be accused of blasphemy.

As a follower of the Lutheran Church, he believed that studying the natural world and uncovering the laws that govern it would bring humanity closer to God.

[27] In Jules Verne's Cinq semaines en ballon (Five Weeks in a Balloon), the character of Joe, the manservant, is described as having, "in common with Maestlin, Kepler's professor, the rare ability to distinguish the satellites of Jupiter with the naked eye, and to count fourteen of the stars in the Pleiades cluster, the remotest of which being only of the ninth magnitude."

From this, Gerhard Betsch produced a collective volume summarizing their findings, which included a breakdown of Maestlin's works and an overview of his nachlass.