Golden ratio

The golden ratio has been used to analyze the proportions of natural objects and artificial systems such as financial markets, in some cases based on dubious fits to data.

Some 20th-century artists and architects, including Le Corbusier and Salvador Dalí, have proportioned their works to approximate the golden ratio, believing it to be aesthetically pleasing.

According to Mario Livio, Some of the greatest mathematical minds of all ages, from Pythagoras and Euclid in ancient Greece, through the medieval Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa and the Renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler, to present-day scientific figures such as Oxford physicist Roger Penrose, have spent endless hours over this simple ratio and its properties.

Biologists, artists, musicians, historians, architects, psychologists, and even mystics have pondered and debated the basis of its ubiquity and appeal.

[13] According to one story, 5th-century BC mathematician Hippasus discovered that the golden ratio was neither a whole number nor a fraction (it is irrational), surprising Pythagoreans.

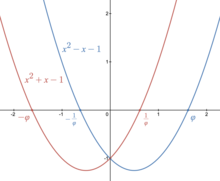

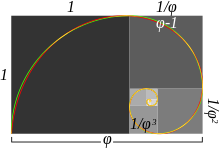

German mathematician Simon Jacob (d. 1564) noted that consecutive Fibonacci numbers converge to the golden ratio;[25] this was rediscovered by Johannes Kepler in 1608.

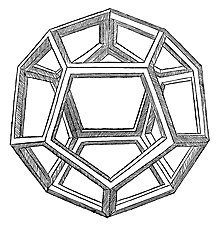

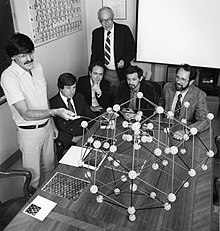

[36] This gained in interest after Dan Shechtman's Nobel-winning 1982 discovery of quasicrystals with icosahedral symmetry, which were soon afterwards explained through analogies to the Penrose tiling.

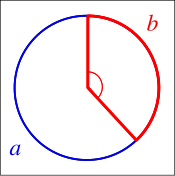

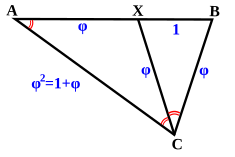

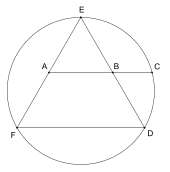

The golden ratio properties of a regular pentagon can be confirmed by applying Ptolemy's theorem to the quadrilateral formed by removing one of its vertices.

[65] This is considerably faster than known algorithms for π and e. An easily programmed alternative using only integer arithmetic is to calculate two large consecutive Fibonacci numbers and divide them.

[69] The Swiss architect Le Corbusier, famous for his contributions to the modern international style, centered his design philosophy on systems of harmony and proportion.

Le Corbusier's faith in the mathematical order of the universe was closely bound to the golden ratio and the Fibonacci series, which he described as "rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another.

He saw this system as a continuation of the long tradition of Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci's "Vitruvian Man", the work of Leon Battista Alberti, and others who used the proportions of the human body to improve the appearance and function of architecture.

In addition to the golden ratio, Le Corbusier based the system on human measurements, Fibonacci numbers, and the double unit.

[73] Leonardo da Vinci's illustrations of polyhedra in Pacioli's Divina proportione have led some to speculate that he incorporated the golden ratio in his paintings.

[74][78] A statistical study on 565 works of art of different great painters, performed in 1999, found that these artists had not used the golden ratio in the size of their canvases.

[82]According to some sources, the golden ratio is used in everyday design, for example in the proportions of playing cards, postcards, posters, light switch plates, and widescreen televisions.

[84] Ernő Lendvai analyzes Béla Bartók's works as being based on two opposing systems, that of the golden ratio and the acoustic scale,[85] though other music scholars reject that analysis.

The golden ratio is also apparent in the organization of the sections in the music of Debussy's Reflets dans l'eau (Reflections in water), from Images (1st series, 1905), in which "the sequence of keys is marked out by the intervals 34, 21, 13 and 8, and the main climax sits at the phi position".

[87] The musicologist Roy Howat has observed that the formal boundaries of Debussy's La Mer correspond exactly to the golden section.

For example, Keith Devlin says, "Certainly, the oft repeated assertion that the Parthenon in Athens is based on the golden ratio is not supported by actual measurements.

[114] Active from 1911 to around 1914, they adopted the name both to highlight that Cubism represented the continuation of a grand tradition, rather than being an isolated movement, and in homage to the mathematical harmony associated with Georges Seurat.

)[116] The Cubists observed in its harmonies, geometric structuring of motion and form, "the primacy of idea over nature", "an absolute scientific clarity of conception".

[117] However, despite this general interest in mathematical harmony, whether the paintings featured in the celebrated 1912 Salon de la Section d'Or exhibition used the golden ratio in any compositions is more difficult to determine.

[119] On the other hand, an analysis suggests that Juan Gris made use of the golden ratio in composing works that were likely, but not definitively, shown at the exhibition.

[119][120] Art historian Daniel Robbins has argued that in addition to referencing the mathematical term, the exhibition's name also refers to the earlier Bandeaux d'Or group, with which Albert Gleizes and other former members of the Abbaye de Créteil had been involved.

[121] Piet Mondrian has been said to have used the golden section extensively in his geometrical paintings,[122] though other experts (including critic Yve-Alain Bois) have discredited these claims.

The Golden Ratio is a standard feature of many modern designs, from postcards and credit cards to posters and light-switch plates.

The Golden Ratio also crops up in some very unlikely places: widescreen televisions, postcards, credit cards and photographs all commonly conform to its proportions.

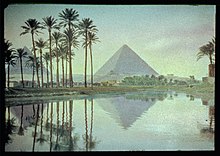

there is no direct evidence in any ancient Egyptian written mathematical source of any arithmetic calculation or geometrical construction which could be classified as the Golden Section ... convergence to

itself as a number, do not fit with the extant Middle Kingdom mathematical sources; see also extensive discussion of multiple alternative theories for the shape of the pyramid and other Egyptian architecture, pp.

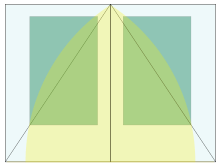

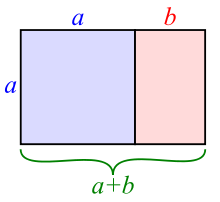

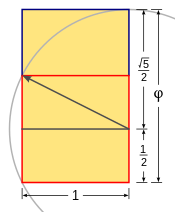

| Draw a square. |

| Draw a line from the midpoint of one side of the square to an opposite corner. |

| Use that line as the radius to draw an arc that defines the height of the rectangle. |

| Complete the golden rectangle. |

|

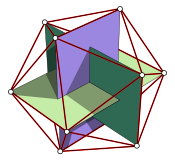

Cartesian coordinates

of the

dodecahedron

:

|

||

| (±1, ±1, ±1) | ||

| (0, ± φ , ± 1 / φ ) | ||

| (± 1 / φ , 0, ± φ ) | ||

| (± φ , ± 1 / φ , 0) | ||

| A nested cube inside the dodecahedron is represented with dotted lines. | ||