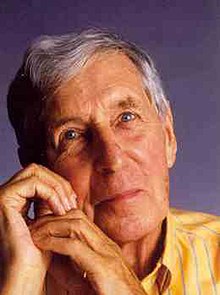

Michael Tippett

[13] Despite his parents' wish that he follow an orthodox path by proceeding to Cambridge University, Tippett had firmly decided on a career as a composer, a prospect that alarmed them and was discouraged by his headmaster and by Sargent.

[17] Life in London widened his musical awareness, especially the Proms at the Queen's Hall, opera at Covent Garden (where he saw Dame Nellie Melba's farewell performance in La bohème) and the Diaghilev Ballet.

[23][24] In February 1930 Tippett provided the incidental music for a performance by his theatrical group of James Elroy Flecker's Don Juan, and in October he directed them in his own adaptation of Stanford's opera The Travelling Companion.

This second RCM period, during which he learned to write fugues in the style of Bach and received additional tuition in orchestration from Gordon Jacob,[23] was central to Tippett's eventual discovery of what he termed his "individual voice".

Having briefly considered the theme of the Dublin Easter Rising of 1916, he based his work on a more immediate event: the murder in Paris of a German diplomat by a 17-year-old Jewish refugee, Herschel Grynszpan.

[46] Tippett called the oratorio A Child of Our Time, taking the title from Ein Kind unserer Zeit, a contemporary protest novel by the Austro-Hungarian writer Ödön von Horváth.

He revived the Morley College Choir and orchestra, and arranged innovative concert programmes that typically mixed early music (Orlando Gibbons, Monteverdi, Dowland), with contemporary works by Stravinsky, Hindemith and Bartók.

Tippett rejected such work as an unacceptable compromise with his principles and in June 1943, after several further hearings and statements on his behalf from distinguished musical figures, he was sentenced to three months' imprisonment in HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs.

His farewell took the form of three concerts he conducted at the new Royal Festival Hall, in which the programmes included A Child of Our Time, the British première of Carl Orff's Carmina Burana, and Thomas Tallis's rarely performed 40-part motet Spem in alium.

[56][73] Tippett's libretto was variously described as "one of the worst in the 350-year history of opera"[72] and "a complex network of verbal symbolism", and the music as "intoxicating beauty" with "passages of superbly conceived orchestral writing".

The Fantasia eventually became one of Tippett's most popular works, though The Times's critic lamented the "excessive complexity of the contrapuntal writing ... there was so much going on that the perplexed ear knew not where to turn or fasten itself".

[80] As with The Midsummer Marriage, Tippett's preoccupation with the opera meant that his compositional output was limited for several years to a few minor works, including a Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis written in 1961 for the 450th anniversary of the foundation of St John's College, Cambridge.

[85] This reception, combined with the fresh acclaim for The Midsummer Marriage following a well-received BBC broadcast in 1963, did much to rescue Tippett's reputation and establish him as a leading figure among British composers.

His eyesight was deteriorating as a result of macular dystrophy, and he relied increasingly on his musical amanuensis Michael Tillett,[101] and on Meirion Bowen, who became Tippett's assistant and closest companion in the remaining years of the composer's life.

[36] Sceptical critics such as the musicologist Derrick Puffett have argued that Tippett's craft as a composer was insufficient for him to deal adequately with the task that he had set himself of "transmut[ing] his personal and private agonies into ... something universal and impersonal".

[135][136] Tippett recognised the importance to his compositional development of several 19th- and 20th-century composers: Berlioz for his clear melodic lines,[134] Debussy for his inventive sound, Bartók for his colourful dissonance, Hindemith for his skills at counterpoint, and Sibelius for his originality in musical forms.

The composer David Matthews writes of passages in Tippett's music which "evoke the 'sweet especial rural scene' as vividly as Elgar or Vaughan Williams ... perhaps redolent of the Suffolk landscape with its gently undulating horizons, wide skies and soft lights".

The mid-1970s produced a further stylistic change, less marked and sudden than that of the early 1960s, after which what Clarke calls the "extremes" of the experimental phase were gradually replaced by a return to the lyricism characteristic of the first period, a trend that was particularly manifested in the final works.

1 (1938) full of the young composer's inventiveness,[98] while Matthews writes of the Concerto for Double String Orchestra (1939): "[I]t is the rhythmic freedom of the music, its joyful liberation from orthodox notions of stress and phrase length, that contributes so much to its vitality".

Tippett had obtained recordings of American singing groups, especially the Hall Johnson Choir,[151] which provided him with a model for determining the relationships between solo voices and chorus in the spirituals.

[151] The composer's instructions in the score specify that "the spirituals should not be thought of as congregational hymns, but as integral parts of the Oratorio; nor should they be sentimentalised but sung with a strong underlying beat and slightly 'swung'".

[121] In his analysis of King Priam, Bowen argues that the change in Tippett's musical style arose initially from the nature of the opera, a tragedy radically different in tone from the warm optimism of The Midsummer Marriage.

[159] Clarke sees the change as something more fundamental, the increases in dissonance and atonality in Priam being representative of a trend that continued and reached a climax of astringency a few years later in Tippett's third opera, The Knot Garden.

2 (1962), Milner thought the new style worked better in the theatre than in the concert or recital hall, although he found the music in the Concerto for Orchestra (1963) had matured into a form that fully justified the earlier experiments.

[163] In The Knot Garden Mellers discerns Tippett's "wonderfully acute" ear only intermittently, otherwise: "thirty years on, the piece still sounds and looks knotty indeed, exhausting alike to participants and audience".

Tippett's intention, explained by the music critic Calum MacDonald, was to explore the contemporary relevance of the grand, universal sentiments in Schiller's Ode to Joy, as set by Beethoven.

The symphony, written in the manner of the tone poem or symphonic fantasia exemplified by Sibelius,[167] represents what Tippett describes as a birth-to-death cycle, beginning and ending with the sounds of breathing.

With the forthcoming centenary celebrations in mind, Lebrecht wrote: "I cannot begin to assess the damage to British music that will ensue from the coming year's purblind promotion of a composer who failed so insistently to observe the rules of his craft".

[117] Geraint Lewis acknowledges that "no consensus yet exists in respect of the works composed from the 1960s onwards", while forecasting that Tippett will in due course be recognised as one of the most original and powerful musical voices of twentieth-century Britain".

[191] In Lambeth, home of Morley College, is Heron Academy (previously named The Michael Tippett School), an educational facility for young people aged 11–19 with complex learning disabilities.