Michael W. Young

[2] At Rockefeller University, his lab has made significant contributions in the field of chronobiology by identifying key genes associated with regulation of the internal clock responsible for circadian rhythms.

He was awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine along with Jeffrey C. Hall and Michael Rosbash "for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm".

[5] His father worked for Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation managing aluminum ingot sales for the south eastern United States.

The book described biological clocks as the reason why a strange plant he had seen years earlier produced flowers that closed during the day and opened at night.

[6] While working as a graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, Michael Young met his future wife Laurel Eckhardt.

[6] Michael Young continued his studies through postdoctoral training at Stanford University School of Medicine with an interest in molecular genetics and particular focus on transposable elements.

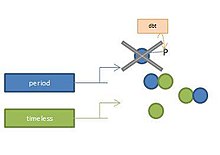

[5] At The Rockefeller University in the early 1980s, Young and his two lab members, Ted Bargiello and Rob Jackson, further investigated the circadian period gene in Drosophila.

In late 1980s, Amita Sehgal, Jeff Price, Bernice Man helped Young use forward genetics to screen for additional mutations that altered fly rhythms.

In 1994, Leslie Vosshall, a graduate student in Young's lab, discovered that if PER proteins were protected from degradation, they would accumulate without TIM, but could not move to the nuclei.

[13] Later studies by the Young, Sehgal, and Edery labs revealed that light causes the rapid degradation of TIM and resets of the phase of the circadian rhythm.