Michelson interferometer

The Michelson interferometer (among other interferometer configurations) is employed in many scientific experiments and became well known for its use by Michelson and Edward Morley in the famous Michelson–Morley experiment (1887)[1] in a configuration which would have detected the Earth's motion through the supposed luminiferous aether that most physicists at the time believed was the medium in which light waves propagated.

The null result of that experiment essentially disproved the existence of such an aether, leading eventually to the special theory of relativity and the revolution in physics at the beginning of the twentieth century.

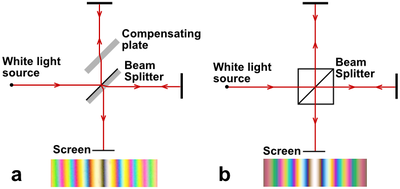

If there is a slight angle between the two returning beams, for instance, then an imaging detector will record a sinusoidal fringe pattern as shown in Fig.

3a, the optical elements are oriented so that S'1 and S'2 are in line with the observer, and the resulting interference pattern consists of circles centered on the normal to M1 and M'2 (fringes of equal inclination).

Even a narrowband (or "quasi-monochromatic") spectral source requires careful attention to issues of chromatic dispersion when used to illuminate an interferometer.

Early experimentalists attempting to detect the Earth's velocity relative to the supposed luminiferous aether, such as Michelson and Morley (1887)[1] and Miller (1933),[5] used quasi-monochromatic light only for initial alignment and coarse path equalization of the interferometer.

(A practical Fourier transform spectrometer would substitute corner cube reflectors for the flat mirrors of the conventional Michelson interferometer, but for simplicity, the illustration does not show this.)

When using a noisy detector, such as at infrared wavelengths, this offers an increase in signal-to-noise ratio while using only a single detector element; (2) the interferometer does not require a limited aperture as do grating or prism spectrometers, which require the incoming light to pass through a narrow slit in order to achieve high spectral resolution.

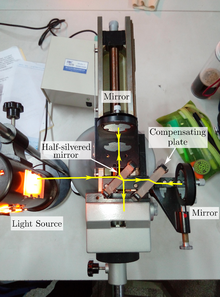

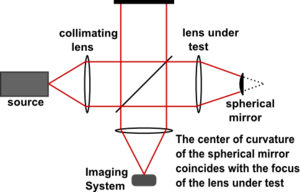

Michelson (1918) criticized the Twyman–Green configuration as being unsuitable for the testing of large optical components, since the available light sources had limited coherence length.

A point source of monochromatic light is expanded by a diverging lens (not shown), then is collimated into a parallel beam.

A similar scheme has been used by Tajammal M in his PhD thesis (Manchester University UK, 1995) to balance two arms of an LDA system.

This involves detecting tiny strains in space itself, affecting two long arms of the interferometer unequally, due to a strong passing gravitational wave.

With the addition of the Virgo interferometer in Europe, it became possible to calculate the direction from which the gravitational waves originate, using the tiny arrival-time differences between the three detectors.

7 illustrates use of a Michelson interferometer as a tunable narrow band filter to create dopplergrams of the Sun's surface.

Michelson interferometers have the largest field of view for a specified wavelength, and are relatively simple in operation, since tuning is via mechanical rotation of waveplates rather than via high voltage control of piezoelectric crystals or lithium niobate optical modulators as used in a Fabry–Pérot system.

Compared with Lyot filters, which use birefringent elements, Michelson interferometers have a relatively low temperature sensitivity.

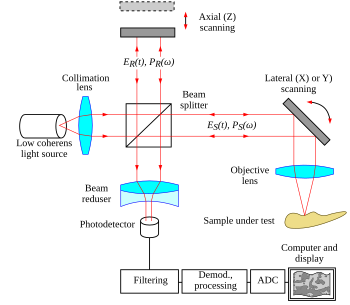

[17] Another application of the Michelson interferometer is in optical coherence tomography (OCT), a medical imaging technique using low-coherence interferometry to provide tomographic visualization of internal tissue microstructures.

[23] The Michelson Interferometer has played an important role in studies of the upper atmosphere, revealing temperatures and winds, employing both space-borne, and ground-based instruments, by measuring the Doppler widths and shifts in the spectra of airglow and aurora.

For example, the Wind Imaging Interferometer, WINDII,[24] on the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite, UARS, (launched on September 12, 1991) measured the global wind and temperature patterns from 80 to 300 km by using the visible airglow emission from these altitudes as a target and employing optical Doppler interferometry to measure the small wavelength shifts of the narrow atomic and molecular airglow emission lines induced by the bulk velocity of the atmosphere carrying the emitting species.

This led to the first polarizing wide-field Michelson interferometer described by Title and Ramsey [26] which was used for solar observations; and led to the development of a refined instrument applied to measurements of oscillations in the Sun's atmosphere, employing a network of observatories around the Earth known as the Global Oscillations Network Group (GONG).

[27] The Polarizing Atmospheric Michelson Interferometer, PAMI, developed by Bird et al.,[28] and discussed in Spectral Imaging of the Atmosphere,[29] combines the polarization tuning technique of Title and Ramsey [26] with the Shepherd et al. [30] technique of deriving winds and temperatures from emission rate measurements at sequential path differences, but the scanning system used by PAMI is much simpler than the moving mirror systems in that it has no internal moving parts, instead scanning with a polarizer external to the interferometer.

The PAMI was demonstrated in an observation campaign [31] where its performance was compared to a Fabry–Pérot spectrometer, and employed to measure E-region winds.

HMI takes high-resolution measurements of the longitudinal and vector magnetic field over the entire visible disk thus extending the capabilities of its predecessor, the SOHO's MDI instrument (See Fig. 9).

[32] HMI produces data to determine the interior sources and mechanisms of solar variability and how the physical processes inside the Sun are related to surface magnetic field and activity.

It also produces data to enable estimates of the coronal magnetic field for studies of variability in the extended solar atmosphere.

HMI observations will help establish the relationships between the internal dynamics and magnetic activity in order to understand solar variability and its effects.

[33] In one example of the use of the MDI, Stanford scientists reported the detection of several sunspot regions in the deep interior of the Sun, 1–2 days before they appeared on the solar disc.

[34] The detection of sunspots in the solar interior may thus provide valuable warnings about upcoming surface magnetic activity which could be used to improve and extend the predictions of space weather forecasts.

is second-order correlation function, the interference curve in phase-conjugating interferometer [36] has much longer period defined by frequency shift

The nontrivial features of phase fluctuations in optical phase-conjugating mirror had been studied via Michelson interferometer with two independent PC-mirrors .