Microglia

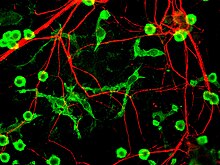

[5][6] Microglia are key cells in overall brain maintenance – they are constantly scavenging the CNS for plaques, damaged or unnecessary neurons and synapses, and infectious agents.

[7] Since these processes must be efficient to prevent potentially fatal damage, microglia are extremely sensitive to even small pathological changes in the CNS.

[9] Microglia also constantly monitor neuronal functions through direct somatic contacts via their microglial processes, and exert neuroprotective effects when needed.

[10][11] The brain and spinal cord, which make up the CNS, are not usually accessed directly by pathogenic factors in the body's circulation due to a series of endothelial cells known as the blood–brain barrier, or BBB.

He went on to characterize microglial response to brain lesions in 1927 and note the "fountains of microglia" present in the corpus callosum and other perinatal white matter areas in 1932.

Then, in 1988, Hickey and Kimura showed that perivascular microglial cells are bone-marrow derived, and express high levels of MHC class II proteins used for antigen presentation.

This confirmed Pio Del Rio-Hortega's postulate that microglial cells functioned similarly to macrophages by performing phagocytosis and antigen presentation.

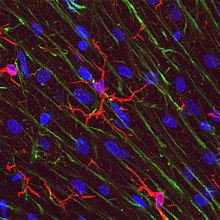

Activated non-phagocytic microglia generally appear as "bushy", "rods", or small ameboids depending on how far along the ramified to full phagocytic transformation continuum they are.

Phagocytic microglia travel to the site of the injury, engulf the offending material, and secrete pro-inflammatory factors to promote more cells to proliferate and do the same.

Amoeboid microglia are especially prevalent during the development and rewiring of the brain, when there are large amounts of extracellular debris and apoptotic cells to remove.

PVMs, unlike normal microglia, are replaced by bone marrow-derived precursor cells on a regular basis, and express MHC class II antigens regardless of their environment.

[citation needed] In addition to being very sensitive to small changes in their environment, each microglial cell also physically surveys its domain on a regular basis.

[30] A large part of microglial cell's role in the brain is maintaining homeostasis in non-infected regions and promoting inflammation in infected or damaged tissue.

[18] As mentioned above, resident non-activated microglia act as poor antigen presenting cells due to their lack of MHC class I/II proteins.

Once they have been presented with antigens, T-cells go on to fulfill a variety of roles including pro-inflammatory recruitment, formation of immunomemories, secretion of cytotoxic materials, and direct attacks on the plasma membranes of foreign cells.

Proteases secreted by microglia catabolise specific proteins causing direct cellular damage, while cytokines like IL-1 promote demyelination of neuronal axons.

Cytotoxic secretion is aimed at destroying infected neurons, virus, and bacteria, but can also cause large amounts of collateral neural damage.

These include synaptic stripping, secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines, recruitment of neurons and astrocytes to the damaged area, and formation of gitter cells.

Without microglial cells regrowth and remapping would be considerably slower in the resident areas of the CNS and almost impossible in many of the vascular systems surrounding the brain and eyes.

[7][34] Recent research verified, that microglial processes constantly monitor neuronal functions through specialized somatic junctions, and sense the "well-being" of nerve cells.

Via this intercellular communication pathway, microglia are capable of exerting robust neuroprotective effects, contributing significantly to repair after brain injury.

However, recent studies show that microglia originate in the yolk sac during a remarkably restricted embryonal period and populate the brain parenchyma guided by a precisely orchestrated molecular process.

[4] Yolk sac progenitor cells require activation colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) for migration into the brain and differentiation into microglia.

Microglia and macrophages both contribute to the immune response by acting as antigen presenting cells, as well as promoting inflammation and homeostatic mechanisms within the body by secreting cytokines and other signaling molecules.

Therefore, instead of constantly being replaced with myeloid progenitor cells, the microglia maintain their status quo while in their quiescent state, and then, when they are activated, they rapidly proliferate in order to keep their numbers up.

[39] Microglia undergo a burst of mitotic activity during injury; this proliferation is followed by apoptosis to reduce the cell numbers back to baseline.

[40] To compensate for microglial loss over time, microglia undergo mitosis and bone marrow derived progenitor cells migrate into the brain via the meninges and vasculature.

"These cells are characterized by abnormalities in their cytoplasmic structure, such as deramified, atrophic, fragmented or unusually tortuous processes, frequently bearing spheroidal or bulbous swellings.

Genes included in the sensome code for receptors and transmembrane proteins on the plasma membrane that are more highly expressed in microglia compared to neurons.

The deletion of CX3CL1, a highly expressed sensome gene, in rodent models of Rett syndrome resulted in improved health and longer lifespan.