Micrometeoroid

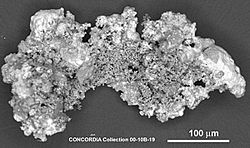

Meteorites and micrometeorites (as they are known upon arrival at the Earth's surface) can only be collected in areas where there is no terrestrial sedimentation, typically polar regions.

[4] Fred Whipple was intrigued by this and wrote a paper that demonstrated that particles of this size were too small to maintain their velocity when they encountered the upper atmosphere.

Direct measurements at the new observatory were used to locate the source of the meteors, demonstrating that the bulk of material was left over from comet tails, and that none of it could be shown to have an extra-solar origin.

In 1957, Hans Pettersson conducted one of the first direct measurements of the fall of space dust on Earth, estimating it to be 14,300,000 tons per year.

To determine whether the direct measurement was accurate, a number of additional studies followed, including the Pegasus satellite program, Lunar Orbiter 1, Luna 3, Mars 1 and Pioneer 5.

[10] Most lunar samples returned during the Apollo Program have micrometeorite impacts marks, typically called "zap pits", on their upper surfaces.

While the tiny sizes of most micrometeoroids limits the damage incurred, the high velocity impacts will constantly degrade the outer casing of spacecraft in a manner analogous to sandblasting.

[12] They also pose major engineering challenges in theoretical low-cost lift systems such as rotovators, space elevators, and orbital airships.

Originally known as a "meteor bumper" and now termed the Whipple shield, this consists of a thin foil film held a short distance away from the spacecraft's body.

[15] The shield allows a spacecraft body to be built to just the thickness needed for structural integrity, while the foil adds little additional weight.