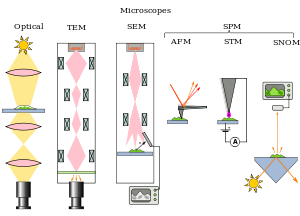

Microscope

[2][3][4] The earliest known examples of compound microscopes, which combine an objective lens near the specimen with an eyepiece to view a real image, appeared in Europe around 1620.

[16] The microscope was still largely a novelty until the 1660s and 1670s when naturalists in Italy, the Netherlands and England began using them to study biology.

[15] A significant contribution came from Antonie van Leeuwenhoek who achieved up to 300 times magnification using a simple single lens microscope.

He sandwiched a very small glass ball lens between the holes in two metal plates riveted together, and with an adjustable-by-screws needle attached to mount the specimen.

[17] Then, Van Leeuwenhoek re-discovered red blood cells (after Jan Swammerdam) and spermatozoa, and helped popularise the use of microscopes to view biological ultrastructure.

In 1965, the first commercial scanning electron microscope was developed by Professor Sir Charles Oatley and his postgraduate student Gary Stewart, and marketed by the Cambridge Instrument Company as the "Stereoscan".

From 1981 to 1983 Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer worked at IBM in Zürich, Switzerland to study the quantum tunnelling phenomenon.

Hamann, while at AT&T's Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey began publishing articles that tied theory to the experimental results obtained by the instrument.

[21] During the last decades of the 20th century, particularly in the post-genomic era, many techniques for fluorescent staining of cellular structures were developed.

It was not until 1978 when Thomas and Christoph Cremer developed the first practical confocal laser scanning microscope and the technique rapidly gained popularity through the 1980s.

Much current research (in the early 21st century) on optical microscope techniques is focused on development of superresolution analysis of fluorescently labelled samples.

Stefan Hell was awarded the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of the STED technique, along with Eric Betzig and William Moerner who adapted fluorescence microscopy for single-molecule visualization.

Technological advances in X-ray lens optics in the early 1970s made the instrument a viable imaging choice.

Magnification of the image is achieved by displaying the data from scanning a physically small sample area on a relatively large screen.

Specialized techniques (e.g., scanning confocal microscopy, Vertico SMI) may exceed this magnification but the resolution is diffraction limited.

In fluorescence microscopy many wavelengths of light ranging from the ultraviolet to the visible can be used to cause samples to fluoresce, which allows viewing by eye or with specifically sensitive cameras.Phase-contrast microscopy is an optical microscopic illumination technique in which small phase shifts in the light passing through a transparent specimen are converted into amplitude or contrast changes in the image.

In addition to, or instead of, directly viewing the object through the eyepieces, a type of sensor similar to those used in a digital camera is used to obtain an image, which is then displayed on a computer monitor.

It has been demonstrated that a light source providing pairs of entangled photons may minimize the risk of damage to the most light-sensitive samples.

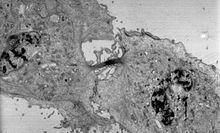

[21][22] Cross-sections of cells stained with osmium and heavy metals reveal clear organelle membranes and proteins such as ribosomes.

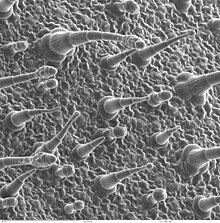

[22] In contrast, the SEM has raster coils to scan the surface of bulk objects with a fine electron beam.

[21] SEM allows fast surface imaging of samples, possibly in thin water vapor to prevent drying.

The microscope can capture either transmitted or reflected light to measure very localized optical properties of the surface, commonly of a biological specimen.

Similar to Sonar in principle, they are used for such jobs as detecting defects in the subsurfaces of materials including those found in integrated circuits.