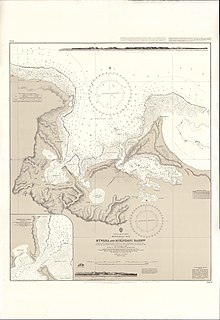

Mikindani

Mikindani was a thriving port in the 19th century, when it participated in the trades of ivory, gum copal, and slaves for the Indian Ocean plantation system.

Mikindani participated in Indian Ocean trade during the first millennium CE, used marine resources with mixed farming subsistence practises, and extensively shared coastal trends.

[4] Recent archaeological studies have substantiated the historical expectations regarding the ancient utilization of the Mikindani Bay area, indicating that human occupation extended into the Late Stone Age, specifically the final centuries before the Common Era .

Notably, the archaeological findings reveal that the inhabitants of Mikindani participated in significant cultural developments associated with Swahili civilization along the East African coast.

This regional importance, coupled with involvement in interregional trade and the relative absence of substantial stone architecture, underscores Mikindani's classification as a mid-level Swahili town during the latter part of the second millennium.

[6] The settlement of Mikindani is first mentioned in written history in the latter half of the eighteenth century in relation to French involvement in the slave trade, although several of these early records, such as one from David Livingstone in 1866, offer architectural evidence for a much longer habitation.

Due to these traits, Makonde communities were able to survive on their own in spite of Portuguese pacification efforts, slave raids, and the actions of many African war leaders.

Even though Swahili people have continuously fought, cooperated with, and been ruled by colonial forces from Europe and the Oman since the sixteenth century, they have managed to preserve their own cultural identity.

[7] Local pottery provide evidence for how the area thrived despite its residents' withdrawal from trade with the Indian Ocean; they relied on connections with interior communities.

They are distinguished by thin-walled, well-fired open bowls and necked vessels with flattened, tapered rims and significant areal stamping or shell-edge impressions on their exteriors.

That Swahili city was well known for controlling access to trade and imported products even inside its own province, and it even claimed some degree of authority over the southern Tanzanian coast.

The similarities in culture that the local ceramics revealed linked Mikindani to the places that the Makonde's oral traditions identified as their ancestral homelands.

The similarities in culture that the local ceramics revealed linked Mikindani to the places that the Makonde's oral traditions identified as their ancestral homelands.

Given the range of Makonde group movements in southern Tanzania since the middle of the eighteenth century that have been historically documented, it is important to remember that the archaeological record should not be interpreted as confirming these oral stories.

[7] However, when combined, these two datasets do indicate that Mikindani's residents, who faced dwindling opportunities in Indian Ocean trade, instead established significant cultural and economic ties with dispersed, expanding, non-Swahili communities in the interior throughout the early second millennium.

While Kilwa's fall brought about previously unattainable opportunities, it also left a void in southern Tanzania that neighbouring Swahili centres hastened to fill.

Since the middle of the eighteenth century, the Omanis have actively participated in coastal politics, first joining forces with different Swahili communities to fight the Portuguese and later pursuing their own colonial ambitions.

This tactic, which mostly left local authority institutions in place and avoided direct control in favour of a scheme of nominal sovereignty and customs taxes, was intended to sustain brisk and profitable trade throughout the Indian Ocean.

In particular, the British compelled the Zanzibari sultanate to sign anti-slavery accords and later served as the agreements' de facto enforcers, foreshadowing the Protectorate system that would take place at the end of the nineteenth century.

In doing so, they expropriated local people and reimagined the relationship between the owner and the slave, establishing a model for commercial agriculture that was later replicated all along the coast, albeit with other crops.

Its peak occurred later than most Swahili cities because of this, but it was nonetheless a port community like Bagamoyo and Kilwa Kivinje that also benefited from shifting trade patterns in the Indian Ocean.

The town's and its area's oral histories were recorded at the request of Carl Velten, the German governor of East Africa's interpreter at the time, in the late nineteenth century.

It, too, highlighted the locals' participation in the slave trade and copal exports in the Indian Ocean, as well as the Sultanate of Zanzibar's significant impact in how the town's residents "learned to do business."

In contrast to practically every other Swahili account, the Makonde were not quickly and completely replaced by Muslim immigration but rather remained a significant part of the history.

[7] Makonde and Arab relationships were said to be tense, with disputes requiring Zanzibari mediation and rumours of men from the Arabian Peninsula robbing locals of their slaves.

This more complicated situation is reminiscent of European accounts from the 1880s that claimed Makonde groups in southern Tanzania recognised the sultan of Zanzibar as the legitimate ruler, but that his rule was largely ineffective once one moved inland, as evidenced by the continued presence of the slave trade.

It has been suggested that these patterns of distribution correspond to the stonetown-controlled dispersal of imported products elsewhere on the coast and that they meet expectations from archaeological applications of Central Place Theory.

As well as the Old Boma significant buildings that have been renovated are the old market, the old bank and the reputed dwelling place of Dr David Livingstone which now houses the town's museum also run by Trade Aid.