Menander I

'Menander the Saviour'; Pali: Milinda), sometimes called Menander the Great,[4][5] was a Greco-Bactrian and later Indo-Greek King (reigned c. 165/155[6] –130 BC) who administered a large territory in the Northwestern regions of the Indian Subcontinent and Central Asia.

Ancient Indian writers indicate that he possibly launched expeditions southward into Rajasthan and as far east down the Ganges River Valley as Pataliputra (Patna) though he failed to retain these conquests.

[9] Buddhist tradition relates that he handed over his kingdom to his son and retired from the world, but Plutarch says that he died in camp while on a military campaign, and that his remains were divided equally between the cities to be enshrined in monuments, probably stupas, across his realm.

The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Ariana, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander—by Menander in particular (at least if he actually crossed the Hypanis towards the east and advanced as far as the Imaüs), for some were subdued by him personally and others by Demetrius, the son of Euthydemus the king of the Bactrians; and they took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis.

In short, Apollodorus says that Bactriana is the ornament of Ariana as a whole; and, more than that, they extended their empire even as far as the Seres and the Phryni.Accounts describe Indo-Greek campaigns to Mathura, Panchala, Saketa, and potentially Pataliputra.

The religious scripture Yuga Purana, which describes events in the form of a prophecy, states: After having conquered Saketa, the country of the Panchala and the Mathuras, the Yavanas (Greeks), wicked and valiant, will reach Kusumadhvaja.

In the West, Menander seems to have repelled the invasion of the dynasty of Greco-Bactrian usurper Eucratides, and pushed them back as far as the Paropamisadae, thereby consolidating the rule of the Indo-Greek kings in the northwestern part of the Indian Subcontinent.

– Then you set to work, I suppose, to have moats dug, and ramparts thrown up, and watch towers erected, and strongholds built, and stores of food collected?

The 1st-2nd century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea further testifies to the reign of Menander and the influence of the Indo-Greeks in India: To the present day ancient drachmae are current in Barygaza, coming from this country, bearing inscriptions in Greek letters, and the devices of those who reigned after Alexander, Apollodorus [sic] and Menander.According to Numismatist Joe Cribb, the accounts of Menander’s kingdom stretching as far as Sialkot, is hard to believe, as there is no numismatic evidence of him east of Taxila,[dubious – discuss] even more hard is to believe is stretching even further east as thought earlier by historians based upon Indian references, which most likely are referring to Kushans.

He was rich too, mighty in wealth and prosperity, and the number of his armed hosts knew no end.Buddhist tradition relates that, following his discussions with Nāgasena, Menander adopted the Buddhist faith: May the venerable Nâgasena accept me as a supporter of the faith, as a true convert from to-day onwards as long as life shall last!He then handed over his kingdom to his son and retired from the world: And afterwards, taking delight in the wisdom of the Elder, he handed over his kingdom to his son, and abandoning the household life for the houseless state, grew great in insight, and himself attained to Arahatship!There is however little besides this testament to indicate that Menander in fact abdicated his throne in favour of his son.

His legacy as a Buddhist arhat reached the Greco-Roman world and Plutarch writes: But when one Menander, who had reigned graciously over the Bactrians, died afterwards in the camp, the cities indeed by common consent celebrated his funerals; but coming to a contest about his relics, they were difficultly at last brought to this agreement, that his ashes being distributed, everyone should carry away an equal share, and they should all erect monuments to him.

"The above seems to corroborate the claim: It is unlikely that Menander’s support of Buddhism was a pious reconstruction of a Buddhist legend, for his deification by later traditions resonates with Macedonian religious trends that granted divine honours to monarchs and members of their family and worshipped them, like Alexander, as gods.

"[22]Minadrasa maharajasa Katiassa divasa 4 4 4 11 pra[na]-[sa]me[da]... (prati)[thavi]ta pranasame[da]... Sakamunisa On the 14th day of Kārttika, in the reign of Mahārāja Minadra, (in the year ...), (the corporeal relic) of Sakyamuni, which is endowed with life... has been established[23] From Alasanda the city of the Yonas came the Thera ("Elder") Yona Mahadhammarakkhita with thirty thousand bhikkhus.A coin of Menander I was found in the second oldest stratum (GSt 2) of the Butkara stupa suggesting a period of additional constructions during the reign of Menander.

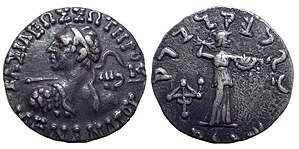

The coins feature the legend (Ancient Greek: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΥ, romanized: BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU / Kharoshthi: MAHARAJA TRATARASA MENADRASA).

Plutarch gives Menander as an example of benevolent rule, contrasting him with disliked tyrants such as Dionysius, and goes on to explain that his subject towns fought over the honour of his burial, ultimately sharing his ashes among them and placing them in "monuments" (possibly stupas), in a manner reminiscent of the funerals of the Buddha.

But if I were to go forth from home into homelessness I would not live long, so many are my enemies".Menander was the last Indo-Greek king mentioned by ancient historians, and developments after his death are therefore difficult to trace.

a) The traditional view, supported by W.W. Tarn and Bopearachchi, is that Menander was succeeded by his queen Agathoclea, who acted as regent to their infant son Strato I until he became an adult and took over the crown.

After the reign of Menander I, Strato I and several subsequent Indo-Greek rulers, such as Amyntas, Nicias, Peucolaus, Hermaeus, and Hippostratus, depicted themselves or their Greek deities forming with the right hand a symbolic gesture identical to the Buddhist vitarka mudra (thumb and index joined together, with other fingers extended), which in Buddhism signifies the transmission of the Buddha's teaching.

Altogether, the conversion of Menander to Buddhism suggested by the Milinda Panha seems to have triggered the use of Buddhist symbolism in one form or another on the coinage of close to half of the kings who succeeded him.

Consistently with this perspective, the actual depiction of the Buddha would be a later phenomenon, usually dated to the 1st century, emerging from the sponsorship of the syncretic Kushan Empire and executed by Greek, and, later, Indian and possibly Roman artists.

Another possibility is that just as the Indo-Greeks routinely represented philosophers in statues (but certainly not on coins) in Antiquity, the Indo-Greek may have initiated anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha in statuary only, possibly as soon as the 2nd-1st century BC, as advocated by Foucher and suggested by Chinese murals depicting Emperor Wu of Han worshipping Buddha statues brought from Central Asia in 120 BC (See picture).

Stylistically, Indo-Greek coins generally display a very high level of Hellenistic artistic realism, which declined drastically around 50 BC with the invasions of the Indo-Scythians, Yuezhi and Indo-Parthians.

The college was founded in part by Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, an Indian leader of the Dalit Buddhist movement and writer to the constitution of the Republic of India.

Obv: Menander throwing a spear.

Rev: Athena with thunderbolt. Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΥ (BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU), "Of King Menander, the Saviour".

Obv: Greek legend, ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΥ (BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU) lit. "Of Saviour King Menander".

Rev: Kharosthi legend: MAHARAJASA TRATARASA MENAMDRASA "Saviour King Menander". Athena advancing right, with thunderbolt and shield. Taxila mint mark.

Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΥ

(BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU)

lit. "Of Saviour King Menander". British Museum .

Obv: Conjugate busts of Strato and Agathokleia. Greek legend: BASILEOS SOTEROS STRATONOS KAI AGATOKLEIAS "Of King Strato the Saviour and Agathokleia".

Rev: Athena throwing thunderbolt. Kharoshthi legend: MAHARAJASA TRATASARA DHARMIKASA STRATASA "King Strato, Saviour and Just (="of the Dharma")".