Kharosthi

[8][9] Scholars are not in agreement as to whether the Kharosthi script evolved gradually, or was the deliberate work of a single inventor.

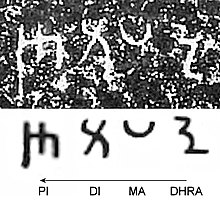

An analysis of the script forms shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications.

Kharosthi seems to be derived from a form of Aramaic used in administrative work during the reign of Darius the Great, rather than the monumental cuneiform used for public inscriptions.

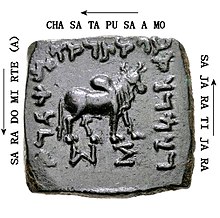

[6] The Kharosthi script was deciphered separately almost concomitantly by James Prinsep (in 1835, published in the Journal of the Asiatic society of Bengal, India)[11] and by Carl Ludwig Grotefend (in 1836, published in Blätter für Münzkunde, Germany),[12] with Grotefend "evidently not aware" of Prinsep's article, followed by Christian Lassen (1838).

[13] They all used the bilingual coins of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (obverse in Greek, reverse in Pali, using the Kharosthi script).

[6] The study of the Kharosthi script was recently invigorated by the discovery of the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, a set of birch bark manuscripts written in Kharosthi, discovered near the Afghan city of Hadda just west of the Khyber Pass in Pakistan.

This alphabet was used in Gandharan Buddhism as a mnemonic for the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, a series of verses on the nature of phenomena.

Each syllable includes the short /a/ sound by default[citation needed], with other vowels being indicated by diacritic marks.

A further diacritic, the double ring below ⟨𐨍⟩ appears with vowels -a and -u in some Central Asian documents, but its precise phonetic function is unknown.