Military history of Cambodia

The presence of shoulder decorations and armour suggests a distinct military and/or clan culture, that has, according to some authors similarities with the Thai Iron Age sites such as Noen U-Loke and Ban Non Wat.

Some modern historians such as M. Vickery have redirected research and focus on archaeology, local genealogy and examined the suspicious size fluctuations and curious shifts of central power that characterized Chenla.

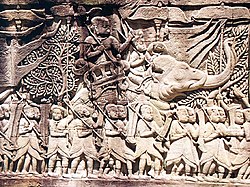

[16] Bas-relief in galleries of the Angkor complex in Siem Reap elaborately depict the empire's land and naval forces and conquests of the period (802 to 1431), as it extended its dominions to encompass most of Indochina.

[31][32] Heavy taxation, institutionalisation of land ownership, reforms, that weakened the privileged status of the Cambodian elite, as well as resentment against foreign domination, were the causes of intermittent rebellions that marked the colonial period.

Under the French pre-World War II colonial regime, the constabulary consisted of a force of about 2,500 men and a mixed Franco–Khmer headquarters element of about forty to fifty officers, technicians, and support personnel.

[35] During World War II Japan which effectively controlled South-east Asia by 1942 tolerated the Vichy administration in Hanoi as a vassal of Nazi Germany that included permission of unhindered movement of Japanese troops through Indochina.

The Khmer Issarak (nationalist insurgents with Thai backing), declared opposition to a French return to power, proclaimed a government-in-exile, and established a base in Battambang Province.

[41][42] By July 1949 Cambodian forces were granted autonomy within operational sectors beginning in the provinces of Siem Reap and Kampong Thom and in 1950 provincial governors received the assignment to oversee the pacification of their jurisdiction, supported by an independent infantry company.

By the mid-1960s, large areas within Cambodia served as supply routes and strategic staging sites for North - and South Vietnamese communists and Viet Cong forces.

[45] Unable to effectively combat Vietnamese presence in Eastern Cambodia Sihanouk, in a gesture of appeasement secretly offered the deep-water port of Sihanoukville, situated at the Gulf of Thailand as a supply terminal for the NVA.

FARK's role as a centrally lead operative force eroded further and increasingly functioned as a highly corrupt arbiter of uncontrolled weapon deals and as shipment agency.

[45][49] In 1967 FARK brutally suppressed the Samlaut Uprising of frustrated peasants in Battambang Province who, among other things, protested against government price dumping for rice, treatment by local military, land displacement and poor socio-economic conditions.

"[45] In January 1970 a group of FARK officers under general Lon Nol exploited Sihanouk's absence to carry out a coup d'État that was confirmed by the National Assembly of Cambodia two months later.

The coup passed without any violent incidents and all FARK contingents, around 35,000 to 40,000 troops, organised mainly as ground forces remained alert, manned and secured key strategic positions.

[45] From 29 April and 1 May 1970, South Vietnamese and United States ground forces entered eastern Cambodia and captured vast quantities of enemy matériel, destroyed NVA and Viet Cong infrastructure and depots.

Although martial law was declared and total mobilization introduced, reliable and transparent administration, replacement of incompetent and corrupt officers, important personnel and educational reforms based on a modern military doctrine did not take place.

The majority of the population occupied these rich, rice-growing areas as Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge control constituted the forested and mountainous lands north and east of the "Lon Nol Line."

[52] By 1972 FANK actions were mainly defensive operations for steadily shrinking government territory which by November 1972 had reached a point that required a new strategic realignment of the Lon Nol line.

[50] The 68,000 troops of Democratic Kampuchea were led by a small group of intellectuals, inspired by Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution in China who aimed to convert Cambodia into an agrarian Utopia.

The command structure in units was firmly based on an extreme form of peasant communist ideology with three-person committees where the political commissar ranked highest.

Democratic Kampuchea attempts to capture several disputed insular territories in the Gulf of Thailand (e.g. Thổ Chu and Phú Quốc[58]) ended, apart from high civilian losses, in failure.

[59] Twelve to fourteen divisions and three Khmer regiments - the future nucleus of KPRAF - launched an offensive on 25 December 1978, with a total invasion force comprising some 100,000 troops.

The Vietnamese and the People's Republic of Kampuchea government's K5 Plan[63] (also known as the Bamboo Curtain) established trenches, wired fences, and extensive minefields along the 700 km (430 mi) border with Thailand.

NADK forces consisted of former RAK troops, conscripts forcibly recruited during the 1978/79 retreat, and personnel pressed into service during in-country raids or drawn from refugees and new volunteers.

Led by senior figures such as Son Sen, Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary and Ta Mok with an unclear hierarchy and loyalty structure, the NADK units were "less experienced, less motivated, and younger" than the early to mid 1970s generation of Khmer Rouge fighters.

It was consolidated by General Dien Del (Chief of Staff) from various anticommunist groups, former Khmer Republic soldiers, refugees, and retreating military and insurgency combatants at the Thai border.

The ANS only began to develop a professional and effective military structure with the formation of the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea, which introduced international shipments of supplies and armaments (mostly Chinese equipment).

Furthermore, the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) would require an effective Khmer military force that eventually could replace NVA units in future security tasks.

The establishment of a sovereign ethnic Khmer army also addressed the problem of traditional fears and widespread hate towards the Vietnamese among the population, and was instrumental for the upkeep of public order.

Designated by Hanoi as "The Vietnamese volunteer army in Kampuchea", the PAVN force, comprising some ten to twelve divisions, was made up of conscripts who supported a "regime of military administration."