Khmer Empire

[6] Researchers have determined that a period of strong monsoon rains was followed by a severe drought in the region, which caused damage to the empire's hydraulic infrastructure.

Historians generally agree that this period of Cambodian history began in 802, when Jayavarman II conducted a grandiose consecration ritual on the sacred Mount Mahendraparvata, now known as Phnom Kulen.

[10]: 97–101 This classical theory was criticized by modern scholars such as Claude Jacques[16] and Michael Vickery, who noted that the Khmer used the term chvea to describe the Chams, their neighbors to the east.

Indravarman I (reigned 877–889) managed to expand the kingdom without wars and initiated extensive building projects, which were enabled by the wealth gained through trade and agriculture.

Finally, in 1177 the capital was raided and looted in a naval battle on the Tonlé Sap lake by a Cham fleet under Jaya Indravarman IV, and Khmer king Tribhuvanadityavarman was killed.

He consequently ascended to the throne and continued to wage war against Champa for another 22 years, until the Khmer defeated the Chams in 1203 and conquered large parts of their territory.

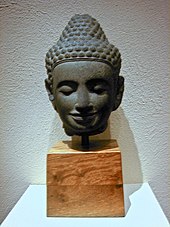

In the center, the king (himself a follower of Mahayana Buddhism) had constructed as the state temple the Bayon,[11]: 378–382 with towers bearing faces of the boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara, each several meters high, carved out of stone.

Further important temples built under Jayavarman VII were Ta Prohm for his mother, Preah Khan for his father,[11]: 388–389 Banteay Kdei, and Neak Pean, as well as the reservoir of Srah Srang.

[35] Jayavarman VIII avoided war with general Sogetu (sometimes known as Sagatu or Sodu), the governor of Guangzhou, China, by paying annual tribute to the Mongols, starting in 1285.

Historians have proposed different causes for the decline: the religious conversion from Vishnuite-Shivaite Hinduism to Theravada Buddhism that affected social and political systems, incessant internal power struggles among Khmer princes, vassal revolt, foreign invasion, plague, and ecological breakdown.

The final fall of Angkor would then be due to the transfer of economic – and therewith political – significance, as Phnom Penh became an important trade center on the Mekong.

Under the rule of Khmer king Barom Reachea I (reigned 1566–1576), who temporarily succeeded in driving back Ayutthaya, the royal court was briefly returned to Angkor.

The farmers, who formed the majority of the kingdom's population, planted rice near the banks of the lake or river, in the irrigated plains surrounding their villages, or in the hills when the lowlands were flooded.

Located by the massive Tonlé Sap lake, and also near numerous rivers and ponds, many Khmer people relied on fresh water fisheries for their living.

The marketplace of Angkor contained no permanent buildings; it was an open square where the traders sat on the ground on woven straw mats and sold their wares.

So when a Chinese man goes to this country, the first thing he must do is take in a woman, partly with a view of profiting from her trading abilities.The women age very quickly, no doubt because they marry and give birth when they are too young.

[47] The king and his officials were in charge of irrigation management and water distribution, which consisted of an intricate series of hydraulics infrastructure, such as canals, moats, and massive reservoirs called barays.

Society was arranged in a hierarchy reflecting the Hindu caste system,[citation needed] where the commoners – rice farmers and fishermen – formed the large majority of the population.

The state religion was Hinduism but influenced by the cult of Devaraja, elevating the Khmer kings as possessing the divine quality of living gods on earth, attributed to the incarnation of Vishnu or Shiva.

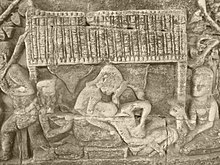

Zhou Daguan's description of a royal procession of Indravarman III is as follows:[49] When the king goes out, troops are at the head of [his] escort; then come flags, banners and music.

The elephant's tusks are encased in gold.Zhou Daguan's description of the Khmer king's wardrobe:[46] Only the ruler can dress in cloth with an all-over floral design...Around his neck he wears about three pounds of big pearls.

At his wrists, ankles and fingers he has gold bracelets and rings all set with cat's eyes...When he goes out, he holds a golden sword [of state] in his hand.Khmer kings were often involved in series of wars and conquests.

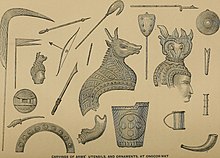

[50] The Khmer had double bow crossbows mounted on elephants, which Michel JacqHergoualc'h suggests were elements of Cham mercenaries in Jayavarman VII's army.

[51] In terms of fortifications, Zhou described Angkor Thom's walls as being 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) long in circumference with five gateways, each with two gates, surrounded by a large moat spanned by bridges.

Open corridors and long colonnades, arranged in harmonious patterns, stretch away on all sides.Kambuja produced numerous temples and majestic monuments to celebrate the divine authority of Khmer kings.

The relations with the Yuan dynasty was of great historical significance, since it produced The Customs of Cambodia (真臘風土記), an important insight into the Khmer Empire's daily life, culture and society.

Unlike earlier Tai polities that had a relatively flat hierarchy, Ayutthaya adopted Angkor's more complex social stratification, the deification of kings (Devaraja) as well as Khmer honorifics and elaborate Brahmanic rituals.

Specialist staff in early Ayutthaya, like scribes, court Brahmans, jurists, chamberlains, accountants, physicians and astrologers, usually came from the Khmer-speaking elites of city-states in the eastern Chaophraya Basin that had been under the influence of the Khmer Empire.

A Javanese source, the Nagarakretagama canto 15, composed in 1365 in the Majapahit Empire, claimed Java had established diplomatic relations with Kambuja (Cambodia) together with Syangkayodhyapura (Ayutthaya), Dharmmanagari (Negara Sri Dharmaraja), Rajapura (Ratchaburi) and Singhanagari (Songkla), Marutma (Martaban or Mottama, Southern Myanmar), Champa, and Yawana (Annam).

[66] This record describes the political situations in Mainland Southeast Asia in the mid-14th century; although the Cambodian polity still survived, the rise of Siamese Ayutthaya had taken its toll.