Military history of France

Under Louis XIV France achieved military supremacy over its rivals, but escalating conflicts against increasingly powerful enemy coalitions checked French ambitions and left the kingdom bankrupt at the opening of the 18th century.

[2] In the last few centuries, French strategic thinking has sometimes been driven by the need to attain or preserve the so-called "natural frontiers," which are the Pyrenees to the southwest, the Alps to the southeast, and the Rhine River to the east.

Warfare with other European powers was not always determined by these considerations, and often rulers of France extended their continental authority far beyond these barriers, most notably under Charlemagne, Louis XIV, and Napoleon.

[6] Starting in the early 16th century, much of France's military efforts were dedicated to securing its overseas possessions and putting down dissent among both French colonists and native populations.

Unencumbered by continental wars or intricate alliances, France now deploys its military forces as part of international peacekeeping operations, security enforcers in former colonies, or maintains them combat ready and mobilized to respond to threats from rogue states.

[16] Cavalry dominated the battlefields, and while the high costs associated with equipping horses and horse-riders helped limit their numbers, Carolingian armies maintained an average size of 20,000 during peacetime by recruiting infantry from imperial territories near theaters of operation, swelling to more with the levies called upon when at war.

[18] A smaller and more mobile elite cavalry force quickly grew to be the most important component of armies within French territories and most of the rest of Europe,[19] with the shock charge they provided becoming the standard tactic on the battlefield when it was invented in the 11th century.

[20] At the same time, the development of agricultural techniques allowed the nations of Western Europe to radically increase food production, facilitating the growth of a particularly large aristocracy under Capetian France.

Some scholars believe that one of the driving forces behind the Crusades was an attempt by such landless knights to find land overseas, without causing the type of internecine warfare that would largely damage France's increasing military strength.

New weapons, including artillery, and tactics seemingly made the knight more of a sitting target than an effective battle force, but the often-praised longbowmen had little to do with the English success.

Popular conceptions of the third and final phase of the Hundred Years War are often dominated by the exploits of Joan of Arc, but French resurgence was rooted in multiple factors.

A major step was taken by King Charles VII, who created the Compagnies d'ordonnance—cavalry units with 20 companies of 600 men each[32]—and launched the first standing army for a dynastic state in the Western world.

As nobles managed to raise their own private armies, these conflicts between Huguenots and Catholics all but demolished centralization and monarchical authority, precluding France from remaining a powerful force in European affairs.

The French strategic situation, however, changed decisively with the Glorious Revolution in England, which replaced a pro-French king with an enemy of Louis, the Dutch William of Orange.

Wars in this era consisted mostly of sieges and movements that were rarely decisive, prompting the French military engineer Vauban to design an intricate network of fortifications for the defense of France.

In the mid-17th century, royal power reasserted itself and the army became a tool through which the King could wield authority, replacing older systems of mercenary units and the private forces of recalcitrant nobles.

18th-century armies—with their rigid protocols, static operational strategy, unenthusiastic soldiers, and aristocratic officer classes—underwent massive remodeling as the French monarchy and nobility gave way to liberal assemblies obsessed with external threats.

The changes also placed a faith on the ordinary soldier that would be completely unacceptable in earlier times; French troops were expected to harass the enemy and remain loyal enough to not desert, a benefit other Ancien Régime armies did not have.

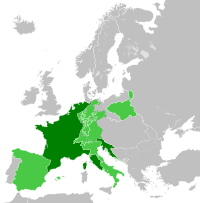

By 1797 the French had defeated the First Coalition, occupied the Low Countries, the west bank of the Rhine, and Northern Italy, objectives which had defied the Valois and Bourbon dynasties for centuries.

Clausewitz correctly analyzed the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras to give posterity a thorough and complete theory of war that emphasized struggles between nations occurring everywhere, from the battlefield to the legislative assemblies, and to the very way that people think.

The French army did use a convoy system, but it was stocked with very few days worth of food; Napoleon's troops were expected to march quickly, effect a decision on the battlefield, then disperse to feed.

Not used to such catastrophic defeats in the rigid power system of 18th-century Europe, many nations found existence under the French yoke difficult, sparking revolts, wars, and general instability that plagued the continent until 1815, when the forces of reaction finally triumphed at the Battle of Waterloo.

Following defeat in the Seven Years' War, France lost its possessions in North America and India, but it did manage to keep the wealthy Caribbean islands of Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Martinique.

[59] France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War led to the loss of Alsace-Lorraine and the creation of a united German Empire, both results representing major failures in long-term French foreign policy and sparking a vengeful, nationalist revanchism meant to earn back former territories.

Prior to the Battle of France, there were sentiments among many Allied soldiers, French and British, of pointless repetition; they viewed the war with dread since they had already beaten the Germans once, and images of that first major conflict were still poignant in military circles.

Nonetheless, several colonies in the Pacific, Caribbean, Indian Oceans and South America remain French territory to this day and France kept a form of indirect political influence in Africa colloquially known as the Françafrique.

This process has not been immune to budget cuts—in October 2013 France announced the closure of her last infantry regiment in Germany, thus marking the end of a major presence across the Rhine although both countries will maintain around 500 troops on each other's territory.

This has occurred both at government level and in industrial programmes like the SEPECAT Jaguar whilst corporate mergers have seen Thales and MBDA emerge as major defence companies spanning both countries.

At the Battle of Bir Hakeim in 1942, the Free French 13th Legion Demi-Brigade doggedly defended its positions against a combined Italian-German offensive and seriously delayed Rommel's attacks towards Tobruk.

At the climactic Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, French forces, many of them legionnaires, were completely surrounded by a large Vietnamese army and were defeated after two months of tenacious fighting.