Military history of Spain

With the fall of the Roman Empire, Spain was devastated by successive barbarian invasions, with stability only gradually appearing with the later years of the Visigothic kingdom.

The early Middle Ages for Spain saw the country forming the front line in a battle between Christian and Islamic forces in the Mediterranean; the Conquista and Reconquista took centuries to reach a military resolution.

In the post-war period, Spain has increasingly turned away from the last remaining colonial conflicts in Africa, and played a growing modern military role within the context of the NATO alliance.

In the troubled final years of the Republic, Quintus Sertorius held most of Iberia as a de facto independent sovereign against the partisans of Sulla.

The Islamic offensive ultimately paused after the losses it suffered in Frankland and in the Asturias, where battles such as those at Tours and Covadonga showed some of the potential weaknesses of the Arab methods of warfare.

Thereafter, Ferdinand III of Castile retook Córdoba in 1236, Jaén in 1246, and Seville in 1248; then he took Arcos, Medina-Sidonia, Jerez and Cádiz, effectively bringing the bulk of the reconquista to a conclusion.

Late medieval Spain was divided into the three Christian kingdoms of Navarre, Castile and Aragon, alongside the small, last remaining Islamic state of Granada.

The civil wars and conflicts of the late 14th and early 15th century would result in the unification of the Christian kingdoms; combined with advances in naval technology, this would pave the way for the rise of Spain as a dominant European power.

The efforts of Ferdinand Magellan, reaching the island of Limasawa in 1521,[10] led to the subsequent establishment of the colony of the Philippines under Miguel López de Legazpi which was to become an essential Spanish military base in the Pacific.

The challenge of the Barbary Pirates encouraged defensive and punitive expeditions across the Mediterranean, resulting in the conquest of various outposts in North Africa, including Melilla in 1497, Mazalquivir in 1505, Oran in 1509, Algiers in 1510, Tripoli in 1511 and the smaller Plazas de Soberania.

Both wars in which very small numbers of Spanish soldiers – the conquistadors – who were mostly veterans of Spain's European or North African campaigns, were backed by local allies and defeated well established empires, shared many similarities.

The highly proficient conquistadors benefited from their access to cavalry, steel swords, axes, spears, pikes, halberds, bows, crossbows, helmets and armour, not to mention small cannon, none of which were familiar to local forces.

[14] Habsburg Spain came to enjoy an axis of allied and neutral territories from Naples through Milan and northwards to the Netherlands, a route for reinforcements that came to be called the Spanish Road.

The fleet rose at one time in 1625 to 108 ships of war at sea, without counting the vessels at Flanders, and the crews are the most skillfull mariners this realm ever possessed.

This very year of 1626 we have had two royal armies in Flanders and one in the Palatinate, and yet all the power of France, England, Sweden, Venice, Savoy, Denmark, Holland, Brandenburg, Saxony, and Weimar could not save them from our victorious arms.

Spain's holdings in Italy and the Low Countries contributed large amounts of men and treasure to the empire's army: each province was allotted a number of troops it had to pay for (including the ethnic Spanish garrisons) and recruits it had to provide.

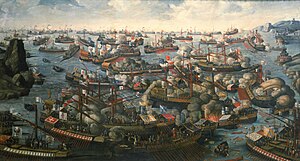

[21] In the east, Habsburg Spain fought alongside other Christian allies against the Ottoman Empire, taking part in numerous actions and campaigns in and around the Mediterranean over the period.

[22][23] The Manila galleons sailed once or twice per year across the Pacific Ocean, whilst the Spanish treasure fleets linked Mexico back to Europe.

Spain entered the conflict with a strong position, but the ongoing fighting gradually eroded her advantages; first Dutch, then Swedish innovations had made the tercio more vulnerable, having less flexibility and firepower than its more modern equivalents.

Attacks on Spanish possessions, such as the amphibious assaults launched during the War of Jenkins' Ear usually ended in failure as their overstretched forces failed to overcome well led defensive actions.

Any sizeable concentration of enemy soldiers had to be engaged, or at least contained, by a sufficiently strong force of Imperial troops; otherwise they were free to go on the rampage with impunity.

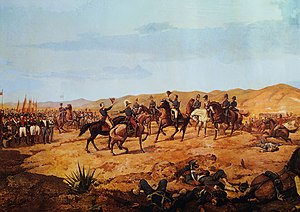

Spain's colonies in the Americas had shown an increasing independence in the years running up to the Peninsular War; British attempts to invade the Río de la Plata in 1806–07, for example, had been rebuffed by well organised local militia.

Ultimately, Royalist exhaustion and growing political maturity amongst the new states resulted in the creation of a chain of newly independent countries stretching from Argentina and Chile in the south to Mexico in the north.

Spain faced a sequence of challenges across her colonies in the second half of the century that would result in a total defeat of empire at the hands of the growing power of the United States.

Spain, although militarily occupied with the Carlist troubles at home, put increasing resources into the conflict, slowly taking the upper hand,[43] and assisted by American sales of modern weaponry.

Cuba gained its independence and Spain lost its remaining New World colony, Puerto Rico, which together with Guam and the Philippines it ceded to the United States for 20 million dollars.

Although Spain remained neutral during World War I, despite suffering considerable economic losses to German submarines,[45] she was militarily active elsewhere during the early part of the 20th century, attempting to strengthen her position in North Africa.

The ensuing Civil War devastated Spain, ending with the victory of the rebels and the founding of the Spanish State, led by caudillo Francisco Franco, the leader of the Nationalist army.

Nearly fifty thousand Spanish personnel served from June 1941 til October 1943, seeing fierce action in the Siege of Leningrad and the Battle of Krasny Bor.

[51] In the 1970s, the rise of another insurgency movement, Polisario, resulted in the Western Sahara War (1973–1991), with Spain withdrawing from its colony in 1975 and transferring its support in the continuing conflict to Morocco.