Firedamp

Often hyphenated as fire-damp, this term for a flammable type of underground mine gas in first part derives via the Old English fyr, and from the proto-Germanic fūr for "fire" (the origin of the same word in Dutch and German, with similar original spellings in Old Saxon, Frisian, and Norse, as well as Middle Dutch and Old High German).

[4] Even after the safety lamps were brought into common use, firedamp explosions could still be caused by sparks produced when coal contaminated with pyrites was struck with metal tools.

[4] The problem of firedamp in mines had been brought to the attention of the Royal Society by 1677[5] and in 1733 James Lowther reported that as a shaft was being sunk for a new pit at Saltom near Whitehaven there had been a major release when a layer of black stone had been broken through into a coal seam.

The blower was panelled off from the shaft and piped to the surface, where more than two and a half years later it continued as fast as ever, filling a large bladder in a few seconds.

[6] The society members elected Sir James Fellow but were unable to come up with any solution nor improve on the assertion (eventually found to be incorrect) of Carlisle Spedding, the author of the paper, that "this sort of Vapour, or damp Air, will not take Fire except by Flame; Sparks do not affect it, and for that Reason it is frequent to use Flint and Steel in Places affected with this sort of Damp, which will give a glimmering Light, that is a great Help to the Workmen in difficult Cases."

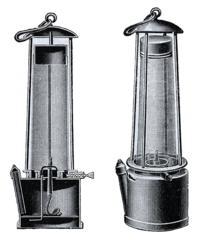

The height of the cone of burning methane in a flame safety lamp can be used to estimate the concentration of the gas in the local atmosphere.