Minor v. Happersett

The Supreme Court readily accepted that Minor was a citizen of the United States, but it held that the constitutionally protected privileges of citizenship did not include the right to vote.

[3] Minor v. Happersett continued to be cited in support of restrictive election laws of other types until the 1960s, when the Supreme Court started interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause to prohibit discrimination among citizenry in voting rights.

[11] The Supreme Court observed that the sole point at issue was whether the Constitution entitled women to vote despite state laws limiting this right to men only.

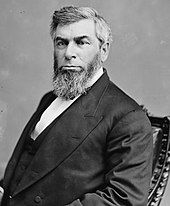

[13] The opinion (written by Chief Justice Morrison Waite) first asked whether Minor was a citizen of the United States, and answered that she was, citing both the Fourteenth Amendment and earlier common law.

For example, at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, none of the original Thirteen Colonies gave all citizens the right to vote, all attaching restrictions based on factors such as sex, race, age, and ownership of land.

"[17] The Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1920, prohibited sex-based denial or abridgment of any United States citizen's right to vote—thus effectively overruling the key holding in Minor v. Happersett.

[4] In his dissenting opinion in Reynolds v. Sims (1964) involving reapportionment in the Alabama state legislature, Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan II included Minor in a list of past decisions about voting and apportionment which were no longer being followed.