Regencies on behalf of Isabella II

Upon the death of Ferdinand VII, his wife Maria Christina immediately assumed the regency on behalf of their daughter, and promised the liberals a policy different from that of the deceased king.

A large part of Spanish society hoped for political reforms once Isabella II came of age that would reflect the liberal models that had developed in some nations of Europe.

On the continent, with the dissolution of the Holy Alliance in 1830, France had overthrown absolutism with the fall of Charles X and established a constitutional monarchy in the person of Louis-Philippe d'Orleans, under whose rule the Industrial Revolution was launched and the bourgeoisie took the reins of the national economy.

Absolutism was relegated to Prussia, Russia and Austria, although in the former the impulses of unification with the German Customs Union, nourished by the liberals, who will not cease to obtain partial successes in the commercial field, will open the borders and will procure advances in the new pre-industrial society.

A bloody civil war began, characterized by its remote geographical locations, as it took place in the Basque Country and Navarre and in some small pockets in Catalonia, Aragon and Valencia.

Spanish troops invaded Portugal in an attempt to eliminate their support to Carlism but with the mediation of England, Carlos was exiled to Great Britain, from where he would escape in 1834 to appear between Navarre and the Basque Country and lead the Carlist War.

In 1832 Francisco Cea Bermúdez had been appointed President of the Council of Ministers, linked to the most right wing of the moderates, who initiated minor administrative reforms but lacked the capacity and interest to facilitate the incorporation of many former enlightened and liberal members into the new model of economic and political development.

Among the reforms of the cabinet of Cea Bermúdez, a new division of Spain into provinces, promoted by the Secretary of State for Public Works, Javier de Burgos, stood out, aimed at improving the administration, which, with some adjustments, is still in place today.

The lack of harmony between economic and political liberalism and the Government led the Regent to dismiss Cea Bermúdez and to the appointment of Martínez de la Rosa as the new president, in January 1834.

At the same time, the climate of confrontation intensified due to the intrigues of the Regent against the liberals and a cholera epidemic that devastated Spain from south to north, generating the hoax that the Church had poisoned the wells and canals that supplied Madrid with drinking water.

Given the anarchy of the country, the Queen Regent was forced to appoint a progressive government, led by Juan Álvarez Mendizábal, who quickly initiated a series of reforms that would lead Spain to become a more modern state.

According to Mendizábal, to make Spain a liberal country, economically and politically speaking, the following steps had to be taken: the elimination of the seigniorial regime, the dissociation of the lands (ending the majorat), and the ecclesiastical and civil confiscation.

Mendizábal argues that it solves the problem of the Treasury by saving public debt; it justifies a socioeconomic reform based on the free market, promoting individual interest; and it says that this sale of goods would create a broad group of support for the Isabellin cause.

The Regent, however, offered the Head of Government to José María Queipo de Llano, who, three months after accepting, presented his resignation because of the violent clashes that took place in Barcelona and an uprising that formed revolutionary juntas similar to those of the War of Independence period.

The revolutionaries presented the Regent with a list of conditions in which they demanded an enlargement of the Militia, freedom of the press, a revision of the electoral regulations that would allow more heads of families to vote, and the convocation of the Cortes Generales.

Aware of the situation, the new president reached an agreement with the liberals: the revolutionary juntas were to be dissolved and integrated into the administrative organization of the State, within the provincial deputation, in exchange for the political and economic reforms that he undertook to carry out.

Although the military troops were increased to 75,000 new men and a greater contribution of 20 million pesetas was destined to the Carlist War, the reorganization did not please the Regent, who because of it lost authority in the armed forces.

After initial successes, Zumalacárregui lost the Battle of Mendaza on December 12, 1834, and retreated until a new incursion in the spring of 1835 that forced the Regent's followers to position themselves beyond the Ebro River.

Whether it was due to the Carlist offensive or to the very weakness of the political parties or to both phenomena, Calatrava's succession brought three men from the most moderate wing of liberalism to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers in less than a year.

The first was Eusebio Bardají Azara, who acceded after the resignation of Espartero, who preferred to continue the military campaign, and obtained even more prestige when he came down from Navarre with his men to defend the capital from the Carlist troops of General Juan Antonio de Zaratiegui, whom he defeated.

The new president established reforms in local administration that allowed a certain level of state interventionism, and at the same time tried to reconcile the most negative aspects of the confiscation of Mendizábal with the Holy See, especially suspicious of the Spanish Crown since the death of Fernando VII.

In the letter sent to the regent it was said: "There is Madam, who believes that Your Majesty cannot continue governing the nation, whose confidence they say you have lost, for other causes that should be known to you through the publicity given to them", in reference to the secret marriage of Mariia Christina with Agustín Fernando Muñoz y Sánchez contracted three months after the death of her husband, King Ferdinand VII.

With the arrival of General Espartero to power after the "revolution of 1840", the government of Spain is occupied for the first time by a military man, a situation that would become frequent throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

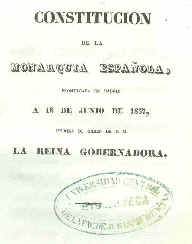

It is a progressive period, since the Constitution of 1837 is still in force, in which there is a great dominance of the head of state, in the hands of General Espartero, born in the province of Ciudad Real in the late eighteenth century from a rather humble family (his father was a craftsman and he was the youngest of eight siblings).

In the 60's of the XIX century he is retired from politics, and after the dethronement of Isabella II at the end of the decade a sector of the liberals offers him to be king of Spain, a position he does not accept.

This meant a direct confrontation with the Church, a diplomatic rupture between Rome and Spain (the Pope was Gregory XVI) and the isolation of Espartero in Europe with respect to the more conservative powers, since he was only supported by England.

In 1843 the regency of Espartero finally came to an end, since after the motion of censure Joaquín María López came to power, who tried to carry out a constitutional reform that would give rise to a parliamentary monarchy.

In view of their impossibility of gaining power by means of suffrage, they opted for the expeditious way of the military takeovers, for which they counted on the help of the previous regent, Maria Christina, exiled in Paris.

Joaquín María López was reinstated by the Cortes in the position of Head of Government on July 23 and to put an end to the Senate where the "esparterists" had the majority, he dissolved it and called elections to renew it completely —which violated article 19 of the Constitution of 1837 that only allowed to do it with a third of it—.

It was then when the "Olózaga incident" took place, which shook political life, since the president of the government was accused by the moderates of having forced the queen to sign the decrees of dissolution and convocation of the Cortes.