LGM-30 Minuteman

However, the development of the United States Navy (USN) UGM-27 Polaris, which addressed the same role, allowed the Air Force to modify the Minuteman, boosting its accuracy enough to attack hardened military targets, including Soviet missile silos.

[21]: 152 To achieve the required energy, that year Hall began funding research at Boeing and Thiokol into the use of ammonium perchlorate composite propellant.

In comparison, older designs burned primarily from one end to the other, meaning that at any instant one small section of the fuselage was being subjected to extreme loads and temperatures.

This met their need for a weapon that would be safe from sneak attacks; hitting all of the silos within a limited time window before they could launch simply did not seem possible.

[21]: 153 But Hall saw solid fuels not only as a way to improve launch times or survivability, but part of a radical plan to greatly reduce the cost of ICBMs so that thousands could be built.

With older designs this had been handled by external systems, requiring miles of extra wiring and many connectors to locations where test instruments could be connected during servicing.

The Air Force and Autonetics spent millions on a program to improve transistor and component reliability 100 times, leading to the "Minuteman high-rel parts" specifications.

With Minuteman, the targeting could be easily changed by loading new trajectory information into the computer's hard drive, a task that could be completed in a few hours.

Earlier ICBMs' custom wired computers, on the other hand, could have attacked only a single target, whose precise trajectory information was hard-coded directly in the system's logic.

These used long and skinny arrow-like shapes that provided aerodynamic lift in the high atmosphere, and could be fitted to existing missiles like Minuteman.

Although Minuteman would not deploy a boost-glide warhead, the extra space proved invaluable in the future, as it allowed the missile to be extended and carry more fuel and payload.

[25]: 46 During Minuteman's early development, the Air Force maintained the policy that the manned strategic bomber was the primary weapon of nuclear war.

Their accuracy was known to be low, on the order of 4 nautical miles (7.4 km; 4.6 mi), but they carried large warheads that would be useful against Strategic Air Command's bombers, which parked in the open.

Based on the same 400 equivalent megatons calculation, they set about building a fleet of 41 submarines carrying 16 missiles each, giving the Navy a finite deterrent that was unassailable.

They were still pressing for the development of newer bombers, like the supersonic B-70, for attacks against military targets, but this role seemed increasingly unlikely in a nuclear war scenario.

[26] Minuteman's selection as the primary Air Force ICBM was initially based on the same "second strike" logic as their earlier missiles: that the weapon was primarily one designed to survive any potential Soviet attack and ensure they would be hit in return.

Additionally, the computers were upgraded with more memory, allowing them to store information for eight targets, which the missile crews could select among almost instantly, greatly increasing their flexibility.

Newer bombers with better survivability, like the B-70, cost many times more than the Minuteman, and, in spite of great efforts through the 1960s, became increasingly vulnerable to surface-to-air missiles.

[citation needed] The Air Force countered that having a variety of platforms complicated the defense; if the Soviets built an effective anti-ballistic missile system of some sort, the ICBM and SLBM fleet might be rendered useless, while the bombers would remain.

[37] It's not clear exactly why the W59 was replaced by the W56 after deployment but issues with "... one-point safety" and "performance under aged conditions" were cited in a 1987 congressional report regarding the warhead.

Beginning in 2005, Mk-21/W87 RVs from the deactivated Peacekeeper missile were replaced on the Minuteman III force under the Safety Enhanced Reentry Vehicle (SERV) program.

The Minuteman III missile entered service in 1970, with weapon systems upgrades included during the production run from 1970 to 1978 to increase accuracy and payload capacity.

However, starting in the mid-1960s, the Soviets began to gain parity with the US and potentially had the capability to target and successfully attack the Minuteman force with an increased number of ICBMs that had greater yields and accuracy than were previously available.

This theory motivated SAC to design a survivable means to launch Minuteman, even if all the ground-based command and control sites were destroyed.

[59]: 13 After thorough testing and modification of EC-135 command post aircraft, the ALCS demonstrated its capability on 17 April 1967 by launching an ERCS configured Minuteman II out of Vandenberg AFB, CA.

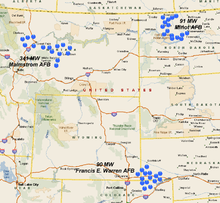

[59]: 14 With the ALCS on alert, the Soviet war planning was complicated by forcing them to target not only the 100 LCCs, but also the 1,000 silos with more than one warhead in order to guarantee destruction.

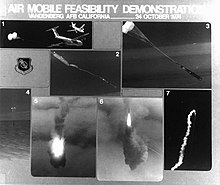

Air-Launched ICBM was a STRAT-X proposal in which SAMSO (Space & Missile Systems Organization) successfully conducted an Air Mobile Feasibility Test that airdropped a Minuteman 1b from a C-5A Galaxy aircraft from 20,000 ft (6,100 m) over the Pacific Ocean.

Operational deployment was discarded due to engineering and security difficulties, and the capability was a negotiating point in the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks.

In 1968, ERCS configurations were placed on the top of modified Minuteman II ICBMs (LGM-30Fs) under the control of the 510th Strategic Missile Squadron located at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri.

More recently, converted Minuteman missiles have been used to power the Minotaur line of rockets produced by Orbital Sciences (nowadays Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems).

1. The missile launches out of its silo by firing its 1st-stage boost motor ( A ).

2. About 60 seconds after launch, the 1st stage drops off and the 2nd-stage motor ( B ) ignites. The missile shroud ( E ) is ejected.

3. About 120 seconds after launch, the 3rd-stage motor ( C ) ignites and separates from the 2nd stage.

4. About 180 seconds after launch, 3rd-stage thrust terminates and the Post-Boost Vehicle ( D ) separates from the rocket.

5. The Post-Boost Vehicle maneuvers itself and prepares for re-entry vehicle (RV) deployment.

6. The RVs, as well as decoys and chaff, are deployed during back away.

7. The RVs and chaff re-enter the atmosphere at high speeds and are armed in flight.

8. The nuclear warheads initiate, either as air bursts or ground bursts.