Miracle of Chile

"[1] The junta to which Friedman refers was a military government that came to power in a 1973 coup d'état, which came to an end in 1990 after a democratic 1988 plebiscite removed Augusto Pinochet from the presidency.

[3] Hernán Büchi, Minister of Finance under Pinochet between 1985 and 1989, wrote a book detailing the implementation process of the economic reforms during his tenure.

Continuing the coalition's free-trade strategy, in August 2006, President Bachelet promulgated a free trade agreement with the People's Republic of China (signed under the previous administration of Ricardo Lagos), the first Chinese free-trade agreement with a Latin American nation; similar deals with Japan and India were promulgated in August 2007.

This repression included assassinations organized under Operation Condor, mass systematized torture, exile, and the international hunting of dissidents.

[5] Rather than a triumph of the free market, the OECD economist Javier Santiso described this reorientation as "combining neo-liberal sutures and interventionist cures".

A week later Ambassador Edward Korry reported telling outgoing Chilean president Eduardo Frei Montalva, through his Defense Minister, that "not a nut or bolt would be allowed to reach Chile under Allende."

[12] According to the 1975 report of a United States Senate Intelligence Committee investigation, the Chilean economic plan was prepared in collaboration with the CIA.

The result, however, was that a serious balance-of-trade problem arose,[14] leading Milton Friedman to criticize De Castro and the fixed exchange rate in his Memoirs ("Chapter 24: Chile", 1998).

Büchi wrote about his experience during this period in his book La transformación económica de Chile: el modelo del progreso.

In 1990, the newly elected Patricio Aylwin government undertook a program of "growth with equity", emphasizing both continued economic liberalization and poverty reduction.

Continuing its export-oriented development strategy, Chile completed landmark free trade agreements in 2002 with the European Union and South Korea.

Chile, as a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) organization, is seeking to boost commercial ties to Asian markets.

In 2008, Chile hopes to conclude an FTA with Australia, and finalize an expanded agreement (covering trade in services and investment) with China.

The P4 (Chile, Singapore, New Zealand, and Brunei) also plan to expand ties through adding a finance and investment chapter to the existing P4 agreement.

[19] Amartya Sen, in his book Hunger and Public Action, examines the performance of Chile in various economic and social indicators.

He finds, from a survey of the literature on the field: The so-called "monetarist experiment" which lasted until 1982 in its pure form, has been the object of much controversy, but few have claimed it to be a success...The most conspicuous feature of the post 1973 period is that of considerable instability...no firm and consistent upward trend (to say the least).Wages decreased by 8%.[20][when?]

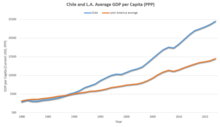

[20] Nobel laureate and economist Gary Becker states that "Chile's annual growth in per capita real income from 1985 to 1996 averaged a remarkable 5 percent, far above the rest of Latin America.

Chile had a very long tradition of public action for the improvement of childcare, which were largely maintained after the Pinochet coup: ... there is little disagreement as to what caused the observed improvement in the area of child health and nutrition...It would be hard to attribute the impressively steady decline in infant mortality ... (despite several major economic recessions) ... to anything else than the maintenance of extensive public support measuresNevertheless, according to libertarian writer Axel Kaiser:[23] In short, thanks to the free‐market reforms introduced by the Chicago Boys and maintained by the democratic regimes that came later, Chile became the most prosperous country in Latin America, which mostly benefitted the poorest members of the population.Performance on economic indicators in comparison to those of other Chilean presidencies:[27] Milton Friedman gave some lectures advocating free market economic policies at the Universidad Católica de Chile.

In 1975, two years after the coup, he met with Pinochet for 45 minutes, where the general "indicated very little indeed about his own or the government's feeling" and the president asked Friedman to write him a letter laying out what he thought Chile's economic policies should be, which he also did.

In October 1975 the New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis declared that "the Chilean junta's economic policy is based on the ideas of Milton Friedman…and his Chicago School".

"[30] Friedman said the "Chilean economy did very well, but more important, in the end the central government, the military junta, was replaced by a democratic society.