Celtic Tiger

The "Celtic Tiger" (Irish: An Tíogar Ceilteach) is a term referring to the economy of Ireland from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s, a period of rapid real economic growth fuelled by foreign direct investment.

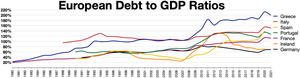

[2] The economy underwent a dramatic reversal from 2008,[3] affected by the Great Recession and ensuing European debt crisis, with GDP contracting by 14%[4] and unemployment levels rising to 14% by 2011.

[8] The term refers to Ireland's similarity to the East Asian Tigers: Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan during their periods of rapid growth between the early 1960s and late 1990s.

An Tíogar Ceilteach, the Irish language version of the term, appears in the Foras na Gaeilge terminology database[9] and has been used in government and administrative contexts since at least 2005.

to state-driven economic development; social partnership among employers, government and trade unions; increased participation by women in the labour force; decades of investment in domestic higher education; targeting of foreign direct investment; a low corporation tax rate; an English-speaking workforce; and membership of the European Union, which provided transfer payments and export access to the Single Market.

Some critics, such as David McWilliams, who had been warning about impending collapse for some time, concluded: "The case is clear: an economically challenged government, perniciously influenced by the interests of the housing lobby, blew it.

[15] In early January 2009, The Irish Times, in an editorial, declared: "We have gone from the Celtic Tiger to an era of financial fear with the suddenness of a Titanic-style shipwreck, thrown from comfort, even luxury, into a cold sea of uncertainty.

"[16][17] In February 2010, a report by Davy Research concluded that Ireland had "largely wasted” its years of high income during the boom, with private enterprise investing its wealth "in the wrong places".

In addition European Union membership was helpful, giving the country lucrative access to markets that it had previously reached only through the United Kingdom, and pumping huge subsidies and investment capital into the Irish economy.

People and businesses expected a stable economy, boosting their confidence to spend and invest due to anticipated stability in output.

[26] These transfer payments from members of the European Union, such as Germany and France, were as high as 4% of Ireland's gross national product (GNP).

The Irish economy's increased productive capacity is sometimes attributed to these investments, which made Ireland more attractive to high-tech businesses,[27] though the libertarian Cato Institute has suggested that the EU transfer payments were economically inefficient and may have actually slowed growth.

Inflation brushed 5% per annum towards the end of the "Tiger" period, pushing Irish prices up to those of Nordic Europe, even though wage rates are roughly the same as in the UK.

[41] An academic said in 2008 that the jumbo breakfast roll became "perhaps the ultimate symbol of our contemporary Celtic Tigerland", product of Irish conglomerate IAWS and eaten by busy workers buying food in filling station convenience stores.

[43] This significantly changed Irish demographics and resulted in expanding multiculturalism[citation needed], particularly in the Dublin, Cork, Limerick, and Galway areas.

[citation needed] Many people in Ireland believe that the growing consumerism during the boom years eroded the country's culture, with the adoption of American capitalist ideals.

[citation needed] Foot and mouth disease and the 11 September 2001 attacks damaged Ireland's tourism and agricultural sectors [dubious – discuss], deterring U.S. and British tourists.

Several companies moved operations to Eastern Europe and the People's Republic of China because of a rise in Irish wage costs, insurance premiums, and a general reduction in Ireland's economic competitiveness.

The EU scarcely grew throughout the whole of 2002, and many members' governments (notably in Germany and France) lost control of public finances, causing large deficits that broke the terms of the EMU Stability and Growth Pact.

[47] In January 2009, UCD economist Morgan Kelly predicted that house prices would fall by 80% from peak to trough in real terms.

[77] The New York Times in 2005 described Ireland as the "Wild West of European finance", a perception that helped prompt the creation of the Irish Financial Services Regulatory Authority.

[84] Outlining possible prospects for the economy for 2008, the ESRI said output of goods and services might fall that year—which would have been the Irish definition of a mild recession.

The recession was confirmed by figures from the Central Statistics Office showing the bursting of the property bubble and a collapse in consumer spending that terminated the boom that was the Celtic Tiger.

[88][89] The figures show the gross domestic product (GDP), which measures the value of all the goods and services produced in the State, fell 0.8% in the second three months of 2008 compared with the same quarter of 2007.

[90] In a November 2008 interview in Hot Press, in a grim assessment of where Ireland stood, then Taoiseach Brian Cowen said many people still did not realise how badly shaken the public finances were.

[91] By 30 January 2009, Ireland's government debt had become the riskiest in the euro zone, surpassing Greece's sovereign bonds, according to credit-default swap prices.

[93] Former Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald blamed Ireland's dire economic state in 2009 on a series of "calamitous" government policy errors.

[94] However, he wrote nothing of the impact of the European Central Bank's low interest rates which funded the property bubble and further exacerbated the overheating economy[95] Nobel laureate Paul Krugman[96] had a bleak prediction,[97][98] “As far as responding to the recession goes, Ireland appears to be really, truly without options, other than to hope for an export-led recovery, if and when the rest of the world bounces back.” The International Monetary Fund in mid-April 2009 forecast a very poor outlook for Ireland.

[99][100] On 19 November 2010, the Irish government began talks on a multibillion-dollar economic assistance package with experts from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Union.

The economic boom led to lower levels of emigration and higher immigration than had historically been the case, while the government of the time acknowledged the continuing strain on some public services and that the "provision of social housing, childcare and the integration of newcomers" remained political priorities.