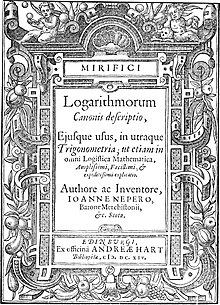

Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio

While others had approached the idea of logarithms, notably Jost Bürgi, it was Napier who first published the concept, along with easily used precomputed tables, in his Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio.

[1][2][3] Prior to the introduction of logarithms, high accuracy numerical calculations involving multiplication, division and root extraction were laborious and error prone.

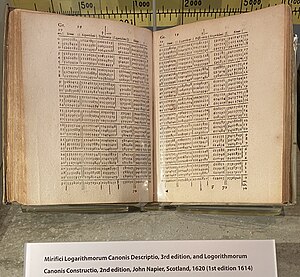

As Napier put it: “…nothing is more tedious, fellow mathematicians, in the practice of the mathematical arts, than the great delays suffered in the tedium of lengthy multiplications and divisions, the finding of ratios, and in the extraction of square and cube roots… [with] the many slippery errors that can arise…I have found an amazing way of shortening the proceedings [in which]… all the numbers associated with the multiplications, and divisions of numbers, and with the long arduous tasks of extracting square and cube roots are themselves rejected from the work, and in their place other numbers are substituted, which perform the tasks of these rejected by means of addition, subtraction, and division by two or three only.”[2]: Preface The book contains fifty-seven pages of explanatory matter and ninety pages of tables of trigonometric functions and their Napierian logarithms.[1]: p.

18 These tables greatly simplified calculations in spherical trigonometry, which are central to astronomy and celestial navigation and which typically include products of sines, cosines and other functions.

16 He wrote a separate volume describing how he constructed his tables, but held off publication to see how his first book would be received.

His son, Robert, published his father's book, Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Constructio, with additions by Henry Briggs in 1619.

[5] [6] The Constructio details how Napier created and used three tables of geometric progressions to facilitate the computation of logarithms of the sine function.

Including a fractional part with a decimal number had been proposed by Simon Stevin but his notation was awkward.

The idea of using a period to separate the integer part of a decimal number from the fractional part was first proposed by Napier himself in his Constructio book, Section 5, “In numbers distinguished thus by a period in their midst, whatever is written after the period is a fraction, the denominator of which is unity with as many cyphers after it as there are figures after the period.“ He used the concept to facilitate more accurate computation of the tables, but not in the printed tables themselves..[1]: p. 22 Thus an angle's sine value published in his table is a whole number representing the length of the side opposite that angle in a right triangle with hypotenuse of 10,000,000 units.

Chapter 1 contains a series of definitions and propositions that explains Napier's conception of logarithms.

The second chapter describes the properties of logarithms and give some formulas (in text form) for working with ratios.

It ends with a note stating he is delaying publication of his work on constructing logarithms until he sees how his invention is received.

The fourth chapter explains how to use the tables and gives worked examples for sines tangents and secants.

32 Napier was reluctant to publish the theory and details of how he created his table of logarithms pending feedback from the mathematics community on his ideas, and he died shortly after publication of the Discriptio.

The volume has a preface by Robert and several appendices, including a section on John Napier's methods for more easily solving spherical triangles, and a section by Henry Biggs on “another and better kind of logarithms,” namely base 10 or common logarithms.

[6] Napier's describes logarithms via a correspondence between two points moving under different speed profiles.

The first point, P, moves along a finite line segment P0 to Q, with an initial speed that decreases proportional to P's distance to Q.

[6]: Sec.16 Similarly, multipliers of the form 1 − 1/(2*10m) (i.e. 0.99...95) only require one shift, one division by two and one subtraction per stage for full precision, which he calls "tolerably easy.

Using his two line model, Napier finds lower and upper bounds for the logarithm of 0.9999999.

His upper bound assumes P started out at its final speed of 0.9999999 in which case L will have moved the distance of (1-0.9999999)/0.9999999.

7 Napier then explains how to use the tables to calculate a bounding interval for logarithms in that range.

Napier then gives instructions for reproducing his published tables, with their seven columns and coverage of each minute of arc.

36 Napier ends by pointing out that two of his methods for extending his table produce results with small differences.

Kepler dedicated his 1620 Ephereris to Napier, with a letter congratulating him on his invention and its benefits to astronomy.

"[6]: p.158 Three hundred years later, in 1914, E. W. Hobson called logarithms "one of the very greatest scientific discoveries that the world has seen.

[9] The logarithm function became a staple of mathematical analysis, but printed tables of logarithms gradually diminished in importance in the twentieth century as multiplying mechanical calculators and, later, electronic computers took over high accuracy computation needs.