History of logarithms

The history of logarithms is the story of a correspondence (in modern terms, a group isomorphism) between multiplication on the positive real numbers and addition on the real number line that was formalized in seventeenth century Europe and was widely used to simplify calculation until the advent of the digital computer.

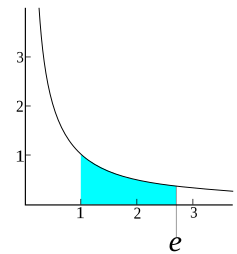

A breakthrough generating the natural logarithm was the result of a search for an expression of area against a rectangular hyperbola, and required the assimilation of a new function into standard mathematics.

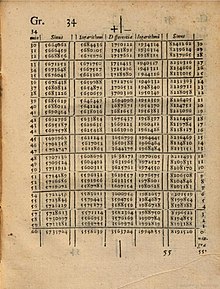

These tables greatly simplified calculations in spherical trigonometry, which are central to astronomy and celestial navigation and which typically include products of sines, cosines and other functions.

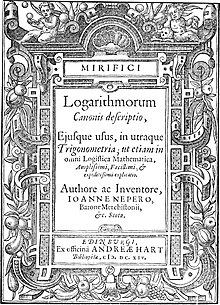

[2] John Napier wrote a separate volume describing how he constructed his tables, but held off publication to see how his first book would be received.

His son, Robert, published his father's book, Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Constructio (Construction of the Wonderful Canon of Logarithms), with additions by Henry Briggs, in 1619 in Latin[3] and then in 1620 in English.

Johannes Kepler praised it; Edward Wright, an authority on navigation, translated Napier's Descriptio into English the next year.

During these conferences the alteration proposed by Briggs was agreed upon, and on his return from his second visit to Edinburgh, in 1617, he published the first chiliad of his logarithms.

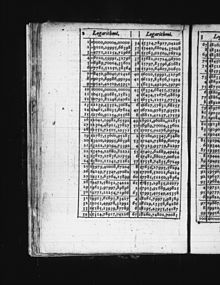

In 1624, Briggs published his Arithmetica Logarithmica, in folio, a work containing the logarithms of thirty thousand natural numbers to fourteen decimal places (1-20,000 and 90,001 to 100,000).

In 1649, Alphonse Antonio de Sarasa, a former student of Grégoire de Saint-Vincent,[8] related logarithms to the quadrature of the hyperbola, by pointing out that the area A(t) under the hyperbola from x = 1 to x = t satisfies[9] At first the reaction to Saint-Vincent's hyperbolic logarithm was a continuation of studies of quadrature as in Christiaan Huygens (1651)[10] and James Gregory (1667).

[11] Subsequently, an industry of making logarithms arose as "logaritmotechnia", the title of works by Nicholas Mercator (1668),[12] Euclid Speidell (1688),[13] and John Craig (1710).

As noted by Howard Eves, "One of the anomalies in the history of mathematics is the fact that logarithms were discovered before exponents were in use.

Indeed, Wittich, who was in Kassel from 1584 to 1586, brought with him knowledge of prosthaphaeresis, a method by which multiplications and divisions can be replaced by additions and subtractions of trigonometrical values.

The method of logarithms was first publicly propounded by John Napier in 1614, in a book titled Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio.

[26] [27] [28] Johannes Kepler, who used logarithm tables extensively to compile his Ephemeris and therefore dedicated it to Napier,[29] remarked: ... the accent in calculation led Justus Byrgius [Joost Bürgi] on the way to these very logarithms many years before Napier's system appeared; but ... instead of rearing up his child for the public benefit he deserted it in the birth.Napier imagined a point P travelling across a line segment P0 to Q.

In modern notation, the relation to natural logarithms is: [33] where the very close approximation corresponds to the observation that The invention was quickly and widely met with acclaim.

The works of Bonaventura Cavalieri (in Italy), Edmund Wingate (in France), Xue Fengzuo (in China), and Johannes Kepler's Chilias logarithmorum (in Germany) helped spread the concept further.

In 1624, Briggs' Arithmetica Logarithmica appeared in folio as a work containing the logarithms of 30,000 natural numbers to fourteen decimal places (1-20,000 and 90,001 to 100,000).

"[40] An edition of Vlacq's work, containing many corrections, was issued at Leipzig in 1794 under the title Thesaurus Logarithmorum Completus by Jurij Vega.

It was begun in 1792, and "the whole of the calculations, which to secure greater accuracy were performed in duplicate, and the two manuscripts subsequently collated with care, were completed in the short space of two years.

Edmund Gunter of Oxford developed a calculating device with a single logarithmic scale; with additional measuring tools it could be used to multiply and divide.

Also like Newton, he became involved in a vitriolic controversy over priority, with his one-time student Richard Delamain and the prior claims of Wingate.

In 1845, Paul Cameron of Glasgow introduced a Nautical Slide-Rule capable of answering navigation questions, including right ascension and declination of the sun and principal stars.

[51][52] Writing in 1914 on the 300th anniversary of Napier's tables, E. W. Hobson described logarithms as "providing a great labour-saving instrument for the use of all those who have occasion to carry out extensive numerical calculations" and comparing it in importance to the "Indian invention" of our decimal number system.[1]: p.

16 Edward Wright, an authority on celestial navigation, translated Napier's Latin Descriptio into English in 1615, shortly after its publication.

It opened the way for the abolition, once and for all, of the infinitely laborious, nay, nightmarish, processes of long division and multiplication, of finding the power and the root of numbers.”[53] The logarithm function remains a staple of mathematical analysis, but printed tables of logarithms gradually diminished in importance in the twentieth century as mechanical calculators and, later, electronic pocket calculators and computers took over computations that required high accuracy.