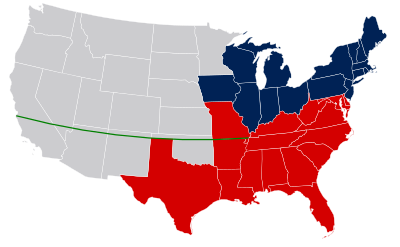

Missouri Compromise

[2] Earlier, in February 1819, Representative James Tallmadge Jr., a Democratic-Republican (Jeffersonian Republican) from New York, had submitted two amendments to Missouri's request for statehood that included restrictions on slavery.

Northern critics including Federalists and Democratic-Republicans objected to the expansion of slavery into the Louisiana purchase territory on the Constitutional inequalities of the three-fifths rule, which conferred Southern representation in the federal government derived from a state's slave population.

Jeffersonian Republicans in the North ardently maintained that a strict interpretation of the Constitution required that Congress act to limit the spread of slavery on egalitarian grounds.

"[3] "The Constitution [said northern Jeffersonians], strictly interpreted, gave the sons of the founding generation the legal tools to hasten [the] removal [of slavery], including the refusal to admit additional slave states.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act effectively repealed the bill in 1854, and the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), both of which increased tensions over slavery and contributed to the American Civil War.

The compromise both delayed the Civil War and sowed its seeds; at that time, Thomas Jefferson predicted the line as drawn would someday tear the Union apart.

[10][11] The economic nationalism of the Era of Good Feelings authorized the Tariff of 1816 and incorporated the Second Bank of the United States, which portended an abandonment of the Jeffersonian political formula for strict construction of the Constitution, a limited central government, and commitments to the primacy of Southern agrarian interests.

In addition, in appointing the officials from the Indiana Territory to Upper Louisiana (as Missouri was known until 1812), Congress heightened concerns that it intended to extend some sort of prohibition on slavery's growth across the river.

Nonetheless, over the next fifteen years, some restrictionists – including Amos Stoddard – claimed that this omission was deliberate, intended to allow the United States government to prohibit slavery in Missouri if circumstances proved more favorable in the future.

[25] In the course of the proceedings, however, Representative James Tallmadge Jr. of New York "tossed a bombshell into the Era of Good Feelings" with the following amendments:[26] Provided, that the further introduction of slavery or involuntary servitude be prohibited, except for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been fully convicted; and that all children born within the said State after the admission thereof into the Union, shall be free at the age of twenty-five years.

[32] In a speech before the House during the debate on the Tallmadge Amendment, Taylor was highly critical of southern lawmakers, who frequently voiced their dismay that slavery was entrenched and necessary to their existence, and he warned that Missouri's fate would "decide the destiny of millions" in future states in the American West.

Dr. Brian Purnell, a professor of Africana Studies and US history at Bowdoin College, writes in Portland Magazine, "Martin Kinsley, Joshua Cushman, Ezekiel Whitman, Enoch Lincoln, and James Parker—wanted to prohibit slavery's spread into new territories.

[42] In a pragmatic commitment to form the Union, the federal apparatus would forego any authority to interfere directly with the institution of slavery if it existed under local control by the states.

They expressed their dissatisfaction in partisan terms, rather than in moral condemnation of slavery, and the pro-De Witt Clinton-Federalist faction carried on the tradition by posing as anti-restrictionists to advance their fortunes in New York politics.

[51][52] Senator Rufus King of New York, a Clinton associate, was the last Federalist icon still active on the national stage, a fact that was irksome to southern Republicans.

In the 15th Congress debates in 1819, he revived his critique as a complaint that New England and the Mid-Atlantic States suffered unduly from the federal ratio and declared himself 'degraded' (politically inferior) to the slaveholders.

[56][57] As determined as southern Republicans were to secure Missouri statehood with slavery, the federal clause ratio failed to provide the margin of victory in the 15th Congress.

[clarification needed] Blocked by northern Republicans, largely on egalitarian grounds, with sectional support from Federalists, the statehood bill died in the Senate, where the federal ratio had no relevance.

[60] The South, voting as a bloc on measures that challenged slaveholding interests and augmented by defections from free states with southern sympathies, was able to tally majorities.

[61][62] Missouri statehood, with the Tallmadge Amendment approved, would have set a trajectory towards a free state west of the Mississippi and a decline in southern political authority.

[65] Jeffersonian Republicans justified Tallmadge's restrictions on the grounds that Congress possessed the authority to impose territorial statutes that would remain in force after statehood was established.

[69] When slaveholders embraced Jeffersonian constitutional strictures on a limited central government, they were reminded that Jefferson, as president in 1803, had deviated from those precepts by wielding federal executive power to double the size of the United States, including the lands under consideration for Missouri statehood.

[82][83] Southern Jeffersonian Republican leadership, including President Monroe and ex-President Thomas Jefferson, considered it as an article of faith that Federalists, given the chance, would destabilize the Union as to restore monarchical rule in North America and "consolidate" political control over the people by expanding the functions of the federal government.

[89][failed verification] The admission of another slave state would increase southern power when northern politicians had already begun to regret the Constitution's Three-Fifths Compromise.

The additional political representation allotted to the South as a result of the Three-Fifths Compromise gave southerners more seats in the House of Representatives than they would have had if the number was based on the free population alone.

[90] A bill to enable the people of the Missouri Territory to draft a constitution and form a government preliminary to admission into the Union came before the House of Representatives in Committee of the Whole, on February 13, 1819.

[91][92] During the following session (1819–1820), the House passed a similar bill with an amendment, introduced on January 26, 1820, by John W. Taylor of New York, allowing Missouri into the union as a slave state.

The influence of Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, known as "The Great Compromiser", an act of admission was finally passed if the exclusionary clause of the Missouri constitution should "never be construed to authorize the passage of any law" impairing the privileges and immunities of any U.S. citizen.

In an April 22 letter to John Holmes, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the division of the country created by the Compromise Line would eventually lead to the destruction of the Union:[98] ...but this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror.

The repeal of the Compromise caused outrage in the North and sparked the return to politics of Abraham Lincoln,[104] who criticized slavery and excoriated Douglas's act in his "Peoria Speech" (October 16, 1854).