Mixtec culture

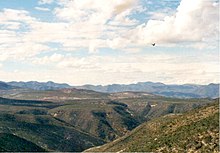

The historical territory of this people is the area known as La Mixteca (Ñuu Dzahui, in ancient Mixtec), a mountainous region located between the current Mexican states of Puebla, Oaxaca, and Guerrero.

There he founded the kingdom of Tututepec (Yucudzáa) and later undertook a military campaign to unify numerous states under his power, including important sites as Tilantongo (Ñuu Tnoo Huahi Andehui).

From here, the border, again in a straight line, runs to San Francisco Telixtlahuaca and Huitzio (Oaxaca); it moves through the rugged ravines of La Culebra and Las Lomas de Alas, and skims the towns of Huitepec, Totomachapa and Teojomulco.

It heads towards the Chinche and La Rana hills, passes them, goes through Mixtepec; turns west towards Manialtepec, collides with that town, resumes its march and ends in the Pacific.

Like most Mesoamerican societies, the Mixtecs did not form a political unit in pre-Hispanic times, but were organized into small states composed of several populations linked by hierarchical relationships.

The settlement pattern of the Mixtecs in those years consisted of small communities dedicated to incipient agriculture, although there is evidence of their incorporation into the international exchange network of Mesoamerica.

[8] On the other hand, in the Olmec nuclear area, Red-on-Bayo ceramic objects have been found that were undoubtedly produced in the region of Tayata, according to the studies that have been carried out on the chemical composition of those archaeological materials.

Towards the end of the Middle Preclassic — a period in which Mesoamerica saw the flourishing of the Olmec style, which was widely spread in the area — some towns began to appear in Highland Mixteca that were home to thousands of people in their heyday.

The political structure at the end of the Late Cruz phase in Highland Mixteca was made up of a series of states that dominated small territories where numerous hierarchically organized populations existed.

The hierarchy of the populations has been observed in the amount of architectural monuments that each locality housed, which has allowed inferring the type of relationships that existed between the center of regional relevance and the second line towns.

Throughout Mesoamerica, cities of considerable dimensions and populations appear, with a clear specialization in the use of space and a social differentiation that is reflected in the diverse characteristics of the remains of the constructions.

[14] However, unlike the Zapotec society, with a single capital in Monte Albán, the Mixtecs were organized in small city-states that rarely exceeded twelve thousand inhabitants.

The relay of Highland Mixteca states seems to have involved a series of events that destabilized the region politically, so that one of the main characteristics of the cities in Ñuiñe is their location in strategic points that facilitated their defense.

[29] In light of these data and the analysis of archaeological artifacts found in the region, it is probable that the linguistic identity of the inhabitants of the lower Verde River valley during the Preclassic and Classic periods was Zapotecan, displaced from central Oaxaca.

Although the relationship between the lower Verde River valley and Highland Mixteca is not completely ruled out due to geographical proximity, the presence of the Mixtecs in the Coastal region is the product of a late colonization.

Ocho Venado was born of the second marriage of Cinco Lagarto-Dzahui Ndicahndíí, priest of the Temple of Heaven that was located in Tilantongo (in Mixtec, Ñuu Tnoo Huahi Andehui).

[35] La Mixteca is strategically located between the central part of Mexico and the Mesoamerican southeast, so that in the time of expansionism of the Triple Alliance formed by Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan —confederation called Excan Tlatoloyan — quickly awakened the interests of the Mexica and their allies in the Texcoco Lake basin.

This means that it was a bilateral system that allowed, among other things, for individuals to have inheritance rights to the property and titles of both their progenitors, as well as the participation of women in high spheres of power, as shown by the 951 noblewomen recorded in the pre-Columbian Mixtec codex.

The goods available to the Mixtecs in those centuries seem to have been limited, and there is no evidence to clearly distinguish the living areas of the elite from the rest of the population, although it is possible to admit the existence of a gradation in the levels of welfare among the inhabitants of the same locality.

The consolidation of state organizations in La Mixteca implied a process of greater differentiation that tended to be legitimized through the use of ideology and alliances at the elite level with the purpose of reproducing the inequalities between the strata of society.

[37] Colonial Spanish chronicles speak of numerous strata of Mixtec society, however, all of them can be reduced to the following major groups:[38] In general, there was not much chance of moving up the social ladder.

The nobles of different Mixtec villages practiced endogamy, which also generated a complicated network of alliances at the elite level that served as a means of reproducing social inequality as well as maintaining order in the region.

These included cotton — which was adapted to the semi-tropical climates of Lowland Mixteca, the Cañada de Cuicatlán, and the Oaxacan coast — and cocoa, which was grown in areas with higher humidity.

It has been proven that during the Middle Preclassic (12th-5th centuries BC), the Red pottery on Bayo de Tayata (Highland Mixteca) was a product of trade with the Olmecs of the Gulf Coast of Mexico.

According to the information that has been obtained from the pictographic documents produced by this people, from colonial historical sources and from the analysis of archaeological evidence, it can be said that it shares with other Mesoamerican religions some very characteristic features, among them, the belief in a primordial dual principle that gave origin to the world as it is known.

He shares many attributes with the Tlaloc of central Mesoamerica, venerated by the Teotihuacan, Toltec, and Mexica and who appears on numerous effigy vessels found especially in Highland Mixteca.

In some effigies obtained in Cerro de las Minas, the Mixtec god of fire appears holding in his hands sahumadores or special vessels to light tobacco.

Stelae have been found in several localities, for example in Yucuita and Yucuñudahui, which show the same Teotihuacan and Zapotec cultural influence that reached the ceramics during the Preclassic and Classic periods.

The Mixtecs produced small sumptuary objects of bone, wood, rock crystal, and semi-precious stones such as jade and turquoise, of such exquisiteness that Alfonso Caso compared them to the "best Chinese carvings".

The clothing of the Postclassic rulers incorporated numerous gold elements, which were combined with a wide variety of objects made of jade, turquoise, feathers, and fine textiles.