Nahuatl

English has also absorbed words of Nahuatl origin, including avocado, chayote, chili, chipotle, chocolate, atlatl, coyote, peyote, axolotl and tomato.

Canger & Dakin (1985) demonstrated a basic split between Eastern and Western branches of Nahuan, considered to reflect the oldest division of the proto-Nahuan speech community.

Canger (1988) tentatively included dialects of La Huasteca in the Central group, while Lastra de Suárez (1986) places them in the Eastern Periphery, which was followed by Kaufman (2001).

[33] Linguists commonly identify localized dialects of Nahuatl by adding as a qualifier the name of the village or area where that variety is spoken.

The language is now called mexicano by many of its native speakers, a term dating to the early colonial period and usually pronounced the Spanish way, with [h] or [x] rather than [ʃ].

[41] Evidence from archaeology and ethnohistory supports the thesis of a southward diffusion across the North American continent, specifically that speakers of early Nahuan languages migrated from Aridoamerica into central Mexico in several waves.

But recently, the traditional assessment has been challenged by Jane H. Hill, who proposes instead that the Uto-Aztecan language family originated in central Mexico and spread northwards at a very early date.

[45][46][47] Before reaching the Mexican Plateau, pre-Nahuan groups probably spent a period of time in contact with the Uto-Aztecan Cora and Huichol of northwestern Mexico.

[49] It was presumed by scholars during the 19th and early 20th centuries that Teotihuacan had been founded by Nahuatl-speakers of, but later linguistic and archaeological research tended to disconfirm this view.

[50] In the late 20th century, epigraphical evidence has suggested the possibility that other Mesoamerican languages were borrowing vocabulary from Proto-Nahuan much earlier than previously thought.

A language which was the ancestor of Pochutec split from Proto-Nahuan (or Proto-Aztecan) possibly as early as AD 400, arriving in Mesoamerica a few centuries earlier than the bulk of Nahuan speakers.

The critically endangered Pipil language of El Salvador is the only living descendant of the variety of Nahuatl once spoken south of present-day Mexico.

By the 11th century, Nahuatl speakers were dominant in the Valley of Mexico and far beyond, with settlements including Azcapotzalco, Colhuacan and Cholula rising to prominence.

The Mexica were among the latest groups to arrive in the Valley of Mexico; they settled on an island in the Lake Texcoco, subjugated the surrounding tribes, and ultimately an empire named Tenochtitlan.

Mexica political and linguistic influence ultimately extended into Central America, and Nahuatl became a lingua franca among merchants and elites in Mesoamerica, such as with the Maya Kʼicheʼ people.

Nahuatl was documented extensively during the colonial period in Tlaxcala, Cuernavaca, Culhuacan, Coyoacan, Toluca and other locations in the Valley of Mexico and beyond.

The types of documentation include censuses, especially one early set from the Cuernavaca region,[58][59] town council records from Tlaxcala,[60] as well as the testimony of Nahua individuals.

[62] For example, some fourteen years after the northeastern city of Saltillo was founded in 1577, a Tlaxcaltec community was resettled in a separate nearby village, San Esteban de Nueva Tlaxcala, to cultivate the land and aid colonization efforts that had stalled in the face of local hostility to the Spanish settlement.

Given the process of marginalization combined with the trend of migration to urban areas and to the United States, some linguists are warning of impending language death.

[70] Today, a spectrum of Nahuan languages are spoken in scattered areas stretching from the northern state of Durango to Tabasco in the southeast.

The dialect spoken in Tetelcingo (nhg) developed the vowel length into a difference in quality:[92] Most varieties have relatively simple patterns of allophony.

[119] Michel Launey argues that Classical Nahuatl had a verb-initial basic word order with extensive freedom for variation, which was then used to encode pragmatic functions such as focus and topicality.

[90][124][127] In the following example, from Michoacán Nahuatl, the postposition -ka meaning 'with' appears used as a preposition, with no preceding object: ti-yayou-goti-k-wikayou-it-carrykawithtelyouti-ya ti-k-wika ka telyou-go you-it-carry with you"are you going to carry it with you?"

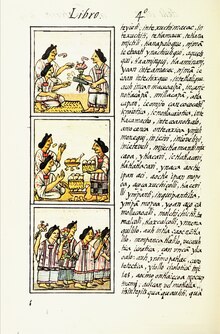

The elaborate codices were essentially pictographic aids for memorizing texts, which include genealogies, astronomical information, and tribute lists.

Annals and chronicles recount history, normally written from the perspective of a particular altepetl (local polity) and often combining mythical accounts with real events.

These works are sometimes evidently based on pre-Columbian pictorial year counts that existed, such as the Cuauhtitlan annals and the Anales de Tlatelolco.

[154] One of the most important works of prose written in Nahuatl is the twelve-volume compilation generally known as the Florentine Codex, authored in the mid-16th century by the Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún and a number of Nahua speakers.

[155] With this work Sahagún bestowed an enormous ethnographic description of the Nahua, written in side-by-side translations of Nahuatl and Spanish and illustrated throughout by color plates drawn by indigenous painters.

Its volumes cover a diverse range of topics: Aztec history, material culture, social organization, religious and ceremonial life, rhetorical style and metaphors.

[153] Aztec poetry makes rich use of metaphoric imagery and themes and are lamentation of the brevity of human existence, the celebration of valiant warriors who die in battle, and the appreciation of the beauty of life.