Mobility transition

It also includes social change, a redistribution of public spaces,[3] and different ways of financing and spending money in urban planning.

The main motivation for mobility transition is the reduction of the harm and damage that traffic causes to people (mostly but not solely due to collisions) and the environment (which also often directly or indirectly affects people) in order to make (urban) society more livable, as well as solving various interconnected logistical, social, economic and energy issues and inefficiencies.

To achieve the goal set in the Paris Agreement, that is, to restrict global warming to clearly below 2 °C, the burning of fossil fuels is to be discontinued around 2040.

[4] Because the CO2 emissions of traffic practically need to be reduced to zero,[5] the measures taken so far in the transport sector are not sufficient in order to achieve the climate change mitigation goals that have been set.

[6] A mobility transition also serves health purposes in the metropolitan regions and large cities and is intended in particular to counteract the massive air pollution.

[9] A 2017 study by the same lead author concluded that air pollution from road traffic in Germany causes 11,000 deaths every year that could potentially be avoided.

[11] Further motives for the mobility transition are the desire for less noise, streets with quality of life and lower accident risks (see also Vision Zero).

According to estimates by the European Environment Agency, 113 million people in Europe are affected by road noise at unhealthy levels.

[12] With increasing traffic and commuter numbers, many citizens also wished for more attractive places to spend time in public spaces.

In the Netherlands, Provo Luud Schimmelpennink's 1965 White Bicycle Plan was an early attempt to stop the rising death toll due to car-related traffic accidents, and to stimulate cycling as a safer and healthier alternative for short-distance travel in the city of Amsterdam.

[23] In Autokind vs Mankind (1971) and On the Nature of Cities (1979), American author Kenneth R. Schneider vehemently criticised the excesses of automobile dependence and called for a struggle to halt and partially reverse negative developments in transportation, although he was largely ignored at the time.

[37][38] Transport scientist Heiner Monheim [de] regards the transition as a "turning away from car subsidies through billions [of euros] in road network expansion".

[39] The Umweltbundesamt announced that in 2018, the sum of all environmentally harmful subsidies in Germany was 65.4 billion euros, almost half of them in the areas of traffic and transport.

In a 2017 position paper, German think tank Agora Verkehrswende described how a climate-neutral conversion of transport would be possible by 2050 without sacrificing mobility.

[45][31] Amongst other things, there were also studies on this in November 2019 by the Verkehrsclub Deutschland [de] (VCD, "Traffic Club Germany") and the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

Numerous regulatory control measures are possible, for example congestion charges, aviation taxation and subsidies (such as a jet fuel tax and a departure tax), a reform of company car taxation, parking space management (for example through pay and display), or an extension of emissions trading to road traffic.

Although the government was free to choose which measures it would take to achieve this reduction, the plaintiff and other environmentalists had been suggesting throughout the legal process to lower the speed limit as one of several effective options to do so.

[57][58][59] As one of several methods to mitigate the environmental impact of aviation, a shift to other modes of transport or a switch from short-haul air traffic to high-speed trains has been proposed.

Cryptic route networks, opaque fare systems, ticket machines that cannot be operated, draft bus stops, and a lack of announcements about transfer and connection options were criticised.

[63] In 2012, several local public transport companies reportedly had been making efforts to improve the usability of ticket machines in Bavaria and Saxony.

The historic city centre of Aix-en-Provence, France is very narrow and closed to cars, taxis and normal bus traffic.

Furthermore, cable cars cause practically no noise pollution on the route, since the individual gondolas do not have their own drive, but are moved by a central motor housed in the station.

As of November 2021, there are projects to build more cable cars to supplement local public transit in Berlin, Bonn, Düsseldorf, Cologne, Munich, Stuttgart and Wuppertal.

[81] In China in particular, the switch from internal combustion engines to electromobility is being promoted for health reasons (to avoid smog) in order to counteract the massive air pollution in the cities.

In the 21st century, several governments, organisations and companies have imposed restrictions and even prohibitions on short-haul flights, stimulating or pressuring travellers to opt for more environmentally friendly means of transportation, especially trains.

As of 2019, the aviation group Airbus was testing this idea on four of its own freighters with the aim of saving up to 8,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions.

The number and carrying capacity of the German inland waterway vessels has remained constant in the early 21st century and was around 2.61 million tonnes in 2015.

At the same time, trolleytrucks would be a cost-effective way to make freight transport climate-friendly, as the electrification of motorways, at a cost of 3 million euros/km, does not represent too much of a financial outlay.

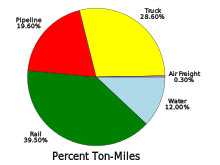

[133] Another option to reduce CO2 emissions and environmental problems is to shift truck traffic to freight rail and inland waterway transport.

The German Environment Agency gives the climate impact of transport by truck in the reference year 2020 as 126 grams of CO2 equivalents per tonne-kilometre on average (g/tkm).