Mogao Caves

[13] Dunhuang was established as a frontier garrison outpost by the Han dynasty Emperor Wudi to protect against the Xiongnu in 111 BC.

It also became an important gateway to the West, a centre of commerce along the Silk Road, as well as a meeting place of various people and religions such as Buddhism.

The caves contain over 400,000 square feet of frescoes and sculptures, making them one of the largest repositories of Buddhist art in the world.

[16] The construction of the Mogao Caves is generally taken to have begun sometime in the fourth century AD, when Dunhuang was under control of the Former Liang dynasty.

According to a book written during the reign of Tang Empress Wu, Fokan Ji (佛龕記, An Account of Buddhist Shrines) by Li Junxiu (李君修), a Buddhist monk named Lè Zūn (樂尊, which may also be pronounced Yuezun) had a vision of a thousand Buddhas bathed in golden light at the site in 366 AD, inspiring him to build a cave here.

The major caves were sponsored by patrons such as important clergy, local ruling elite, foreign dignitaries, as well as Chinese emperors.

During the Ming dynasty, the Silk Road was finally officially abandoned, and Dunhuang slowly became depopulated and largely forgotten by the outside world.

[24] The biggest discovery, however, came from a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu who had appointed himself guardian of some of these temples around the turn of the century and tried to raise funds to repair the statues.

Words of Wang's discovery drew the attention of a joint British/Indian group led by the Hungarian-born British archaeologist Aurel Stein who was on an archaeological expedition in the area in 1907.

In 1956, the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, Zhou Enlai, took a personal interest in the caves and sanctioned a grant to repair and protect the site; and in 1961, the Mogao Caves were declared to be a specially protected historical monument by the State Council, and large-scale renovation work at Mogao began soon afterwards.

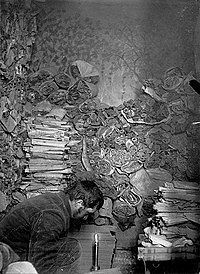

A large number of documents dating from 406 to 1002 were found in the cave, heaped up in closely packed layers of bundles of scrolls.

In addition to the 1,100 bundles of scrolls, there were also over 15,000 paper books and shorter texts, including a Hebrew penitential prayer (selichah) (see Dunhuang manuscripts).

The area left clear within the room was just sufficient for two people to stand in.The Library Cave was walled off sometime early in the 11th century.

Stein first proposed that the cave had become a waste repository for venerable, damaged and used manuscripts and hallowed paraphernalia and then sealed perhaps when the place came under threat.

This theory proposes that the monks of a nearby monastery heard about the fall of the Buddhist kingdom of Khotan to Karakhanids invaders from Kashgar in 1006 and the destruction it caused, so they sealed their library to avoid it being destroyed.

[45] Another possible theory posits that to save the manuscripts from a coming "Age of Decline", the Library Cave was sealed to prevent this from occurring.

[46] It is difficult to determine the state of the materials found since the chamber was not opened "under scientific conditions", so critical evidence to support dating the closure was lost.

[47] The manuscripts found in the Library Cave include the earliest dated printed book, the Diamond Sutra from 868, which was first translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in the fourth century.

These scrolls chronicle the development of Buddhism in China, record the political and cultural life of the time, and provide documentation of mundane secular matters that gives a rare glimpse into the lives of ordinary people of these eras.

Stein had the first pick and he was able to collect around 7,000 complete manuscripts and 6,000 fragments for which he paid £130, although these include many duplicate copies of the Diamond and Lotus Sutras.

Pelliot was interested in the more unusual and exotic of the Dunhuang manuscripts, such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated lay men's groups.

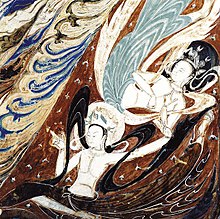

[53] Bodhisattvas started appearing during the Northern Zhou period, with Avalokitesvara (Guanyin), which was originally male but acquired female characteristics later, the most popular.

An innovation of the Sui-Tang period is the visual representation of the sutra – Mahayana Buddhist teachings transformed into large complete and detailed narrative paintings.

The iconography of Tantric Buddhism, such as the eleven-headed or thousand-armed Avalokitesvara, also started to appear in Mogao wall paintings during the Tang period.

For example, scenes depicting General Zhang Yichao, who ruled over Dunhuang in a quasi-autonomous manner during the Late Tang period, include a commemoration of his victory over the Tibetans in 848.

Many early figures in the murals in Dunhuang also used painting techniques originated from India where shading was applied to achieve a three-dimensional or chiaroscuro effect.

The Buddha is generally shown as the central statue, often attended by boddhisattvas, heavenly kings, devas, and apsaras, along with yaksas and other mythical creatures.

[58] The larger northern giant Buddha was damaged in an earthquake and had been repaired and restored multiple times, consequently its clothing, colour and gestures had been changed and only the head retains its original Early Tang appearance.

Possibly these reflect stock for cutting when sold to pilgrims, but inscriptions in some examples show these were also printed out at different times by an individual as a devotion to acquire merit.

[66] The textiles found in the Library Cave include silk banners, altar hangings, wrappings for manuscripts, and monks' apparel (kāṣāya).