Mohammad Mosaddegh

Mohammad Mosaddegh[a] (Persian: محمد مصدق, IPA: [mohæmˈmæd(-e) mosædˈdeɢ] ⓘ;[b] 16 June 1882 – 5 March 1967) was an Iranian politician, author, and lawyer who served as the 30th Prime Minister of Iran from 1951 to 1953, elected by the 16th Majlis.

[10] In the aftermath of the overthrow, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi returned to power, and negotiated the Consortium Agreement of 1954 with the British, which gave split ownership of Iranian oil production between Iran and western companies until 1979.

[12][13] In 2013, the US government formally acknowledged its role in the coup as being a part of its foreign policy initiatives, including paying protestors and bribing officials.

[16][17][18] When Mosaddegh's father died in 1892, his uncle was appointed the tax collector of the Khorasan province and was bestowed with the title of Mosaddegh-os-Saltaneh by Naser al-Din Shah Qajar.

This time he took the lead of Jebhe Melli (National Front of Iran, created in 1949), an organisation he had founded with nineteen others such as Hossein Fatemi, Ahmad Zirakzadeh, Ali Shayegan and Karim Sanjabi, aiming to establish democracy and end the foreign presence in Iranian politics, especially by nationalising the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company's (AIOC) operations in Iran.

In July, Mosaddegh broke off negotiations with AIOC after it threatened to "pull out its employees" and told owners of oil tanker ships that "receipts from the Iranian government would not be accepted on the world market."

[39] This Abadan Crisis reduced Iran's oil income to almost nothing, putting a severe strain on the implementation of Mosaddegh's promised domestic reforms.

[41] The opposition defeated the bill on the grounds that it would "unjustly discriminate patriots who had been voting for the last forty years", thus leaving the National Front to compete against conservatives, royalists, and tribal leaders alike in the upcoming election.

[6] According to historian Ervand Abrahamian: "Realizing that the opposition would take the vast majority of the provincial seats, Mosaddegh stopped the voting as soon as 79 deputies—just enough to form a parliamentary quorum—had been elected.

Woodhouse, chief of the British intelligence station in Tehran, Britain's covert operations network had funnelled roughly £10,000 per month to the Rashidian brothers (two of Iran's most influential royalists) in the hope of buying off, according to CIA estimates, "the armed forces, the Majlis (Iranian parliament), religious leaders, the press, street gangs, politicians and other influential figures".

Conservative, pro-Shah, and pro-British opponents refused to grant Mosaddegh special powers to deal with the economic crisis caused by the sharp drop in revenue and voiced regional grievances against the capital Tehran, while the National Front waged "a propaganda war against the landed upper class".

In response, Mosaddegh announced his resignation, appealing directly to the public for support, pronouncing that "in the present situation, the struggle started by the Iranian people cannot be brought to a victorious conclusion".

The National Front—along with various Nationalist, Islamist, and socialist parties and groups[49]—including Tudeh—responded by calling for protests, assassinations of the Shah and other royalists, strikes, and mass demonstrations in favour of Mosaddegh.

[51] Frightened by the unrest, the Shah asked for Qavam's resignation and re-appointed Mosaddegh to form a government, granting him control over the Ministry of War he had previously demanded.

[53] More popular than ever, a greatly strengthened Mosaddegh introduced a single-clause bill to parliament to grant him emergency "dictatorial decree" powers for six months to pass "any law he felt necessary for obtaining not only financial solvency, but also electoral, judicial, and educational reforms"[54] in order to implement his nine-point reform program and to bypass the stalled negotiations of the nationalisation of the oil industry.

[56] In addition to the reform program, which intended to make changes to a broad region of laws covering elections, financial institutions, employment, the judiciary, the press, education, health, and communications services,[52] Mosaddegh tried to limit the monarchy's powers.

[57] He cut the Shah's personal budget, forbade his direct communications with foreign diplomats, and transferred royal lands back to the state.

Ann Lambton indicates that Mosaddegh saw this as a means of checking the power of the Tudeh Party, who had been agitating the peasants by criticising his lack of significant land reforms.

Hossein Makki strongly opposed the dissolution of the majlis by Mossadegh and evaluated that, because of its closure, the right to dismiss the Prime minister is reserved for the Shah.

[64] Engulfed in a variety of problems following World War II, Britain was unable to resolve the issue single-handedly and looked towards the United States to settle the matter.

After mediation had failed several times to bring about a settlement, American Secretary of State Dean Acheson concluded that the British were "destructive, and determined on a rule-or-ruin policy in Iran.

[67][68][69][70] Though his suggestion was rebuffed by Eisenhower as "paternalistic", Churchill's government had already begun "Operation Boot", and simply waited for the next opportunity to press the Americans.

On 28 February 1953, rumours spread by British-backed Iranians that Mosaddegh was trying to exile the Shah from the country gave the Eisenhower administration the impetus to join the plan.

Finally, to end Mossadegh's destabilising influence that threatened the supply of oil to the West and could potentially pave the way for a communist takeover of the country, the US made an attempt to depose him.

[75] In 2000, The New York Times made partial publication of a leaked CIA document titled Clandestine Service History – Overthrow of Premier Mosaddegh of Iran – November 1952 – August 1953.

The plot, known as Operation Ajax, centered on convincing Iran's monarch to issue a decree to dismiss Mosaddegh from office, as he had attempted some months earlier.

[11] The protests turned increasingly violent, leaving almost 300 dead, at which point the pro-monarchy leadership, led by retired army General and former Minister of Interior in Mosaddegh's cabinet, Fazlollah Zahedi, interceded, joined with underground figures such as the Rashidian brothers and local strongman Shaban Jafari.

[104] Some argue that while many elements of Mosaddegh's coalition abandoned him, it was the loss of support from Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani and another cleric that was fatal to his cause,[102] reflective of the dominance of the Ulema in Iranian society and a portent of the Islamic Revolution to come.

The loss of the political clerics effectively cut Mosaddegh's connections with the lower middle classes and the Iranian masses which are crucial to any popular movement in Iran.

America's close relationship with the Shah and the subsequent hostility of the United States to the Islamic Republic and Britain's profitable interventions caused pessimism for Iranians, stirring nationalism and suspicion of foreign interference.

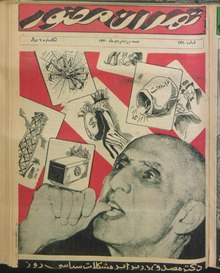

4 January 1952: "Dr. Mosaddegh facing political problems"