Mohr–Coulomb theory

Mohr–Coulomb theory is a mathematical model (see yield surface) describing the response of brittle materials such as concrete, or rubble piles, to shear stress as well as normal stress.

Most of the classical engineering materials follow this rule in at least a portion of their shear failure envelope.

[1] In geotechnical engineering it is used to define shear strength of soils and rocks at different effective stresses.

Coulomb's friction hypothesis is used to determine the combination of shear and normal stress that will cause a fracture of the material.

Mohr's circle is used to determine which principal stresses will produce this combination of shear and normal stress, and the angle of the plane in which this will occur.

According to the principle of normality the stress introduced at failure will be perpendicular to the line describing the fracture condition.

It can be shown that a material failing according to Coulomb's friction hypothesis will show the displacement introduced at failure forming an angle to the line of fracture equal to the angle of friction.

This makes the strength of the material determinable by comparing the external mechanical work introduced by the displacement and the external load with the internal mechanical work introduced by the strain and stress at the line of failure.

By conservation of energy the sum of these must be zero and this will make it possible to calculate the failure load of the construction.

A common improvement of this model is to combine Coulomb's friction hypothesis with Rankine's principal stress hypothesis to describe a separation fracture.

[2] An alternative view derives the Mohr-Coulomb criterion as extension failure.

[3] The Mohr–Coulomb theory is named in honour of Charles-Augustin de Coulomb and Christian Otto Mohr.

Coulomb's contribution was a 1776 essay entitled "Essai sur une application des règles des maximis et minimis à quelques problèmes de statique relatifs à l'architecture" .

[2][4] Mohr developed a generalised form of the theory around the end of the 19th century.

[6] The Mohr–Coulomb[7] failure criterion represents the linear envelope that is obtained from a plot of the shear strength of a material versus the applied normal stress.

This form of the Mohr–Coulomb criterion is applicable to failure on a plane that is parallel to the

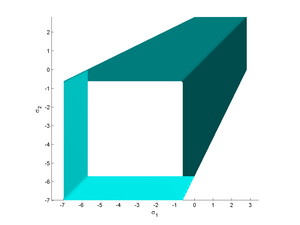

The Mohr–Coulomb criterion in three dimensions is often expressed as The Mohr–Coulomb failure surface is a cone with a hexagonal cross section in deviatoric stress space.

can be generalized to three dimensions by developing expressions for the normal stress and the resolved shear stress on a plane of arbitrary orientation with respect to the coordinate axes (basis vectors).

are three orthonormal unit basis vectors, and if the principal stresses

are The Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion can then be evaluated using the usual expression

are The Mohr–Coulomb failure (yield) surface is often expressed in Haigh–Westergaad coordinates.

as The Haigh–Westergaard invariants are related to the principal stresses by Plugging into the expression for the Mohr–Coulomb yield function gives us Using trigonometric identities for the sum and difference of cosines and rearrangement gives us the expression of the Mohr–Coulomb yield function in terms of

The Mohr–Coulomb yield surface is often used to model the plastic flow of geomaterials (and other cohesive-frictional materials).

Many such materials show dilatational behavior under triaxial states of stress which the Mohr–Coulomb model does not include.

Also, since the yield surface has corners, it may be inconvenient to use the original Mohr–Coulomb model to determine the direction of plastic flow (in the flow theory of plasticity).

A common approach is to use a non-associated plastic flow potential that is smooth.

when the plastic strain is zero (also called the initial cohesion yield stress),

is the angle made by the yield surface in the Rendulic plane at high values of

is an appropriate function that is also smooth in the deviatoric stress plane.

Cohesion (alternatively called the cohesive strength) and friction angle values for rocks and some common soils are listed in the tables below.