Monstrillidae

[2] The name of the first ever described genus Monstrilla is derived from Latin, meaning "tiny monster", because the lack of usual diagnostic features of copepods puzzled early taxonomists.

Females carry a long pair of spines to which the eggs are attached, while males have a "genital protuberance, which is provided with lappets"; in both sexes, the genitalia are very different from those of all other copepods.

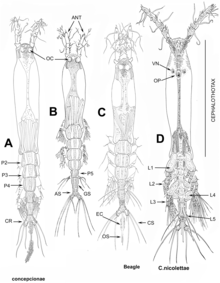

[citation needed] Larval nauplial stages do not possess any discernible antennae, antenullae or mouth parts, but paired tube-shaped nourishing appendages to absorb nutrients from their host, which are also present in later copepodite stages that resemble the adult morphology; in adults, scars of these now discarded appendages remain as small processes on the cephalothorax.

[3] Biologically and ecologically, our knowledge of the order is limited, although the life cycle differs from that of all other copepods:[9] Members of the Monstilloida are protelean parasites, meaning that their larval stages are parasitoids that kill their host to emerge as free-living subadults.

[11] In Contrast to holoplanktonic calanoid and cyclopoid copepods, Monstrilloids do not use their largest cephalic appendages, the antennulae, for locomotion, but to create a stream-line shaped corridor, rather using their four pairs of swimming legs to move in the water column.

Monstrilloida was placed as a sister taxa to the Siphonostomatoida, but a lack of mouth parts makes comparison based on homologies difficult.

Consequently, they would have evolved from an ectoparasitic ancestor associated with fish; most parasitic copepods are not free-living as adults, so Monstrilloids presumably underwent a change in life cycle strategy, host selection and body morphology.