Ocean acidification

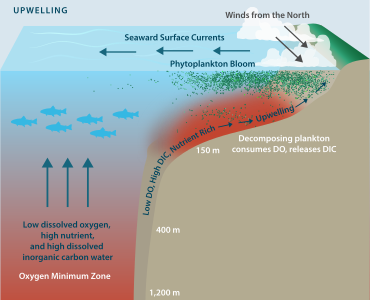

These include ocean currents and upwelling zones, proximity to large continental rivers, sea ice coverage, and atmospheric exchange with nitrogen and sulfur from fossil fuel burning and agriculture.

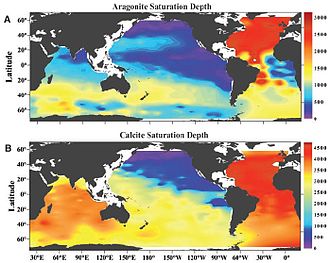

[42] Already now large quantities of water undersaturated in aragonite are upwelling close to the Pacific continental shelf area of North America, from Vancouver to Northern California.

[73] Three of the big five mass extinction events in the geologic past were associated with a rapid increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide, probably due to volcanism and/or thermal dissociation of marine gas hydrates.

[75] Decreased CaCO3 saturation due to seawater uptake of volcanogenic CO2 has been suggested as a possible kill mechanism during the marine mass extinction at the end of the Triassic.

However, stronger proxy methods to test for saturation state are needed to assess how much this pH change may have affected calcifying organisms.

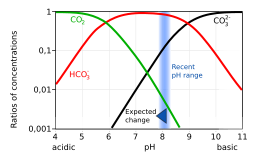

[18][21]: 413 Increasing ocean acidification makes it more difficult for shell-accreting organisms to access carbonate ions, essential for the production of their hard exoskeletal shell.

[92] For example, the oyster Magallana gigas is recognized to experience metabolic changes alongside altered calcification rates due to energetic tradeoffs resulting from pH imbalances.

[94] In particular, studies show that corals,[95][96] coccolithophores,[90][28][97] coralline algae,[98] foraminifera,[99] shellfish and pteropods[100] experience reduced calcification or enhanced dissolution when exposed to elevated CO2.

[107] A study in 2008 examined a sediment core from the North Atlantic and found that the species composition of coccolithophorids remained unchanged over the past 224 years (1780 to 2004).

If the saturation state of aragonite in the external seawater is lower than the ambient level, the corals have to work harder to maintain the right balance in the internal compartment.

[111] An in situ experiment, conducted on a 400 m2 patch of the Great Barrier Reef, to decrease seawater CO2 level (raise pH) to near the preindustrial value showed a 7% increase in net calcification.

[124] Increasing acidity has been observed to reduce metabolic rates in jumbo squid[125] and depress the immune responses of blue mussels.

[142][143] These meta-analyses have been further tested by mesocosm studies that simulated the interaction of these stressors and found a catastrophic effect on the marine food web: thermal stress more than negates any primary producer to herbivore increase in productivity from elevated CO2.

[144][145] The increase of ocean acidity decelerates the rate of calcification in salt water, leading to smaller and slower growing coral reefs which supports approximately 25% of marine life.

[87] Some 1 billion people are completely or partially dependent on the fishing, tourism, and coastal management services provided by coral reefs.

For example, decrease in the growth of marine calcifiers such as the American lobster, ocean quahog, and scallops means there is less shellfish meat available for sale and consumption.

[154] Reducing carbon dioxide emissions (i.e. climate change mitigation measures) is the only solution that addresses the root cause of ocean acidification.

Cost and energy consumed by ocean alkalinity enhancement (mining, pulverizing, transport) is high compared to other CDR techniques.

[159] International efforts, such as the Wider Caribbean's Cartagena Convention (entered into force in 1986),[160] may enhance the support provided by regional governments to highly vulnerable areas in response to ocean acidification.

The Indicators include key information for the most relevant domains of climate change: temperature and energy, atmospheric composition, ocean and water as well as the cryosphere.

[172][173] In 2015, USEPA denied a citizens petition that asked EPA to regulate CO2 under the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 in order to mitigate ocean acidification.

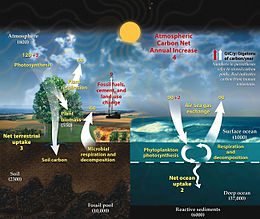

The concept of "too much of a good thing" has been late in developing and was triggered only by some key events, and the oceanic sink for heat and CO2 is still critical as the primary buffer against climate change.

[178] In the early 1970s questions over the long-term impact of the accumulation of fossil fuel CO2 in the sea were already arising around the world and causing strong debate.

By the mid-1990s, the likely impact of CO2 levels rising so high with the inevitable changes in pH and carbonate ion became a concern of scientists studying the fate of coral reefs.

[178] By the end of the 20th century the trade-offs between the beneficial role of the ocean in absorbing some 90 % of all heat created, and the accumulation of some 50 % of all fossil fuel CO2 emitted, and the impacts on marine life were becoming more clear.

[178] In 2009, members of the InterAcademy Panel called on world leaders to "Recognize that reducing the build up of CO2 in the atmosphere is the only practicable solution to mitigating ocean acidification".

[179] The statement also stressed the importance to "Reinvigorate action to reduce stressors, such as overfishing and pollution, on marine ecosystems to increase resilience to ocean acidification".

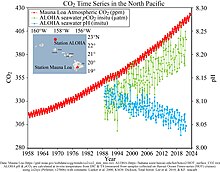

[50] According to a statement in July 2012 by Jane Lubchenco, head of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration "surface waters are changing much more rapidly than initial calculations have suggested.

[95] In a synthesis report published in Science in 2015, 22 leading marine scientists stated that CO2 from burning fossil fuels is changing the oceans' chemistry more rapidly than at any time since the Great Dying (Earth's most severe known extinction event).

[159] Their report emphasized that the 2 °C maximum temperature increase agreed upon by governments reflects too small a cut in emissions to prevent "dramatic impacts" on the world's oceans.

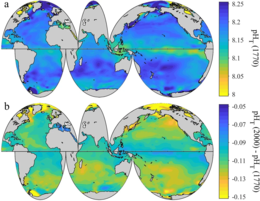

2 levels between the 1700s and the 1990s, from the Global Ocean Data Analysis Project (GLODAP) and the World Ocean Atlas

2 concentration sensor (SAMI-CO 2 ), attached to a Coral Reef Early Warning System station, utilized in conducting ocean acidification studies near coral reef areas (by NOAA ( AOML ))

2 buoy used for measuring CO

2 concentration and ocean acidification studies ( NOAA (by PMEL ))