Montenotte campaign

Montenotte Superiore is located at the junction of Strada Provinciale 12 and 41 in the Liguria region of northwest Italy, 15 kilometres (9 mi) northeast of Carcare municipality.

Leaving a division to observe the stunned Austrians, Bonaparte's army chased the Piedmontese west after a second clash at Ceva.

In two and a half weeks, Bonaparte had overcome one of France's enemies, leaving the crippled Habsburg army as his remaining opponent in northern Italy.

The morale of the army was not of the highest order; the units were strung out in numerous small detachments[...], their communications exposed [...] For their meager rations they were dependent on the whim of fraudulent army contractors, who were amassing private fortunes at the expense of the soldiers [...] officers and men alike [...] quitted their units every day in search of food [...] their pay, already months in arrears [...] relied on the [...] practically bankrupt French Government.

Crossing a divide near the hamlet of Montezemolo, the highway descends into the Tanaro River valley at the small fortress of Ceva.

[7] The battle site at Montenotte Superiore is located on a side road 15 kilometres (9 mi) northeast of Carcare.

After smashing the French right, Sebottendorf would join Eugène-Guillaume Argenteau's 9,000-man Right Wing in crushing Bonaparte's main body near Savona.

Though the Habsburg field army numbered 32,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 148 cannon,[10] four battalions guarded Lombardy, others were marching to the front from their winter quarters in the Po River valley, and thousands were sick.

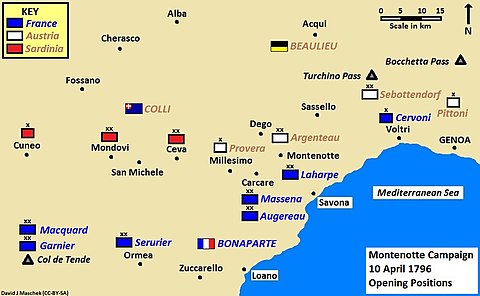

[12] Colli deployed his army between Dego and Cuneo, with his main weight to the west guarding the Col de Tende.

He posted two battalions at Dego and part of Giovanni Marchese di Provera's Austrian brigade at Millesimo.

[13] The French government found it useful to keep Jean-Baptiste Cervoni's brigade at Voltri in order to secure supplies from the nearby Republic of Genoa, which was neutral.

About half of Henri Christian Michel de Stengel's cavalry was with the army, while the rest were en route from France.

[15] Bonaparte planned to commit André Masséna's corps (Laharpe and Meynier) and Augereau to the main attack, while Sérurier threatened Ceva.

On 10 April, the Habsburg army commander accompanied Sebottendorf and 3,200 men as they advanced across the Turchino Pass to attack Cervoni's 5,000 Frenchmen in the Battle of Voltri.

He left two battalions to hold Voltri and sent four more with Josef Philipp Vukassovich to march through the hills to Sassello by a difficult road.

[17] While Laharpe mounted a frontal attack with 7,000 troops from Monte Negino, Masséna moved north with 4,000 men to turn Argenteau's weak right flank.

At dawn on 15 April, Vukassovich surprised Meynier's troops in the act of looting the town and routed the French.

Fearing that Sérurier, who was approaching from Ormea, might attack him in the rear, Colli withdrew to the Corsaglia River at San Michele Mondovi.

Meanwhile, Beaulieu reassembled his battered army near Acqui and Colli directed Jean-Gaspard Dichat de Toisinge with 8,000 soldiers and 15 cannon to defend the Corsaglia position.

[26] On 19 April, Bonaparte ordered Sérurier to attack San Michele while Augereau flanked the river line from the north.

[27] That day, Bonaparte switched his supply line from the exposed Cadibona Pass to a safer route via Imperia and Ormea.

[28] Faced with a heavy French concentration, Colli abandoned the Corsaglia River line on the night of 20/21 April.

The arrival of the ragged and hungry French soldiers in the relatively wealthy plains prompted an outbreak of looting and Bonaparte had several men shot to discourage the practice.

[32] By 25 April, Sérurier was in Fossano on the left flank, Masséna held Cherasco in the center and Augereau occupied Alba on the right, while Laharpe brought up the rear.

[34] By the Armistice of Cherasco, signed on 28 April, territory east of the Stura di Demonte and Tanaro Rivers passed under French control.

[38] Historian Martin Boycott-Brown listed the reasons for Bonaparte's victory:[39] ...not just the disastrous separation between Beaulieu and Argenteau, but also to that between the Austrian and Piedmontese armies.

If the Austrians had chosen to concentrate closer to the Piedmontese positions, as Colli had wanted, it would have been less easy for Bonaparte to effect their separation.

It would be easy to heap the blame for this on Beaulieu, but as we have said before, he was given a difficult hand to play, and if he came off second best in a contest with one of the greatest strategists in the history of war, it is not surprising.