Moon Treaty

It was the first of a series of UN-sponsored conferences intended to create an international framework of laws to guide humanity's use of outer space resources.

The continuing disagreement is based mainly over the meaning of "Common Heritage of Mankind" and on the rights of each country to the natural resources of the Moon.

The opposition, led by Leigh Ratiner of the L-5 Society, stated that the Moon Treaty was opposed to free enterprise and private property rights.

[14] However since rights to economic benefits are claimed to be necessary to ensure investment in private missions to the Moon,[15] private companies in the US have been seeking clearer national regulatory conditions and guidelines[16] prompting the US government to do so, which subsequently legalized space mining in 2015 by introducing the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015.

Therefore it is concluded, that the Moon Treaty is incomplete and lacks an "implementation agreement" answering the unresolved issues, particularly regarding resource extraction.

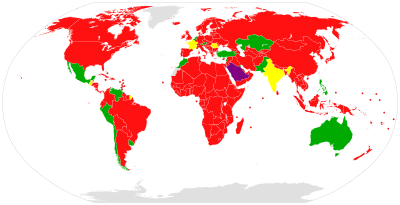

[7] While the treaty reiterates the prohibition of sovereignty of "any part" of space, the current imprecision of the agreement, being called unfinished,[22] generated various interpretations,[8][23] this being cited as the main reason it was not signed by most countries.

[14] An expert in space law and economics summarized that the treaty would need to offer adequate provisions against any one company acquiring a monopoly position in the world minerals market, while avoiding "the socialization of the Moon.

At the time of the signing of the accords U.S. President Donald Trump additionally released an executive order called "Encouraging International Support for the Recovery and Use of Space Resources."

The order emphasizes that "the United States does not view outer space as a 'global commons" and calls the Moon Agreement "a failed attempt at constraining free enterprise.