2 Pallas

Pallas, Vesta and Ceres appear to be the only intact bodies from this early stage of planetary formation to survive within the orbit of Neptune.

[18] When Pallas was discovered by the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers on 28 March 1802, it was considered to be a planet,[19] as were other asteroids in the early 19th century.

[20] The high inclination of the orbit of Pallas results in the possibility of close conjunctions to stars that other solar objects always pass at great angular distance.

This was lost from sight for several months, but was recovered later that year by the Baron von Zach and Heinrich W. M. Olbers after a preliminary orbit was computed by Carl Friedrich Gauss.

By plotting the mean orbital motion, inclination, and eccentricity of a set of asteroids, he discovered several distinct groupings.

[37][38] In some versions of the myth, Athena killed Pallas, daughter of Triton, then adopted her friend's name out of mourning.

[g] The stony-iron pallasite meteorites are not Palladian, being named instead after the German naturalist Peter Simon Pallas.

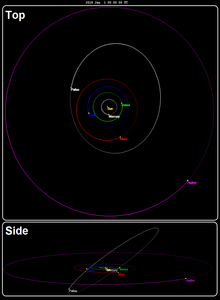

Its orbit is highly inclined and moderately eccentric, despite being at the same distance from the Sun as the central part of the asteroid belt.

[10] This means that every Palladian summer and winter, large parts of the surface are in constant sunlight or constant darkness for a time on the order of an Earth year, with areas near the poles experiencing continuous sunlight for as long as two years.

[45] From Pallas, the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, and Earth can occasionally appear to transit, or pass in front of, the Sun.

[10] Based on spectroscopic observations, the primary component of the material on Pallas's surface is a silicate containing little iron and water.

[50] The surface composition of Pallas is very similar to the Renazzo carbonaceous chondrite (CR) meteorites, which are even lower in hydrous minerals than the CM type.

There is only one clear absorption band in the 3-micron part, which suggests an anhydrous component mixed with hydrated CM-like silicates.

[10] Pallas's surface is most likely composed of a silicate material; its spectrum and calculated density (2.89±0.08 g/cm3) correspond to CM chondrite meteorites (2.90±0.08 g/cm3), suggesting a mineral composition similar to that of Ceres, but significantly less hydrated.

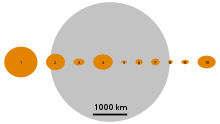

[9] Pallas's shape departs significantly from the dimensions of an equilibrium body at its current rotational period, indicating that it is not a dwarf planet.

Such a migration of water to the surface would have left salt deposits, potentially explaining Pallas's relatively high albedo.

Although other explanations for the bright spot are possible (e.g. a recent ejecta blanket), if the near-Earth asteroid 3200 Phaethon is an ejected piece of Pallas, as some have theorized, then a Palladian surface enriched in salts would explain the sodium abundance in the Geminid meteor shower caused by Phaethon.

In 1980, speckle interferometry suggested a much larger satellite, whose existence was refuted a few years later with occultation data.

A flyby of the Dawn probe's visits to 4 Vesta and 1 Ceres was discussed but was not possible due to the high orbital inclination of Pallas.