Moore v. City of East Cleveland

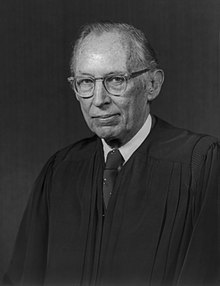

Writing for a plurality of the Court, Associate Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. ruled that the East Cleveland zoning ordinance violated substantive due process because it intruded too far upon the "sanctity of the family.

[16] Justice Powell cited a long line of cases in which the Supreme Court recognized that "freedom of personal choice in matters of marriage and family life is one of the liberties protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

"[19] Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote a concurring opinion in which he emphasized that "the zoning power is not a license for local communities to enact senseless and arbitrary restrictions which cut deeply into private areas of protected family life.

"[20] He stated that he wrote "only to underscore the cultural myopia of the arbitrary boundary drawn by the East Cleveland ordinance in the light of the tradition of the American home," which he argued "displays a depressing insensitivity toward the economic and emotional needs of a very large part of our society.

"[22] Justice John Paul Stevens wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment, in which he argued that the "critical question presented by this case is whether East Cleveland's housing ordinance is a permissible restriction on appellant's right to use her own property as she sees fit".

[23] After reviewing the history of the Court's zoning jurisprudence, Justice Stevens concluded that "[t]here appears to be no precedent for an ordinance which excludes any of an owner's relatives from the group of persons who may occupy his residence on a permanent basis.

Justice Stewart argued that the court's earlier decision in Belle Terre should determine the outcome in this case and that Moore's claims regarding associational freedom and privacy should not invoke constitutional protections.

"[3] Some commentators have also noted that the Moore decision lies at the intersection between the competing goals of controlling population density and maintaining family integrity, but in their rush to overturn "traditional-family ordinances," the Court may have "burn[ed] the house to roast the pig.