The Guide for the Perplexed

All of them that are written down will reach you where you are, one after the other.The part begins with Maimonides' thesis of the unity, omnipresence, and incorporeality of God, explaining biblical anthropomorphism of divine attributes as homonymous or figurative.

The first chapter explains the Genesis 1 description of Adam the first as in the "image of God", as referring to the intellectual perception of humankind rather than physical form.

Maimonides strongly opposed what he believed to be a heresy present in unlearned Jews who then assume God to be corporeal (or even possessing positive characteristics).

This was done by close textual analysis of the word in the Tanakh in order to present what Maimonides saw as the proof that according to the Tanakh, God is completely incorporeal: [The Rambam] set up the incorporeality of God as a dogma, and placed any person who denied this doctrine upon a level with an idolater; he devoted much of the first part of the Moreh Nevukhim to the interpretation of the Biblical anthropomorphisms, endeavoring to define the meaning of each and to identify it with some transcendental metaphysical expression.

"[6] Unrestrained anthropomorphism and perception of positive attributes is seen as a transgression as serious as idolatry, because both are fundamental errors in the metaphysics of God's role in the universe, and that is the most important aspect of the world.

While he accepts the conclusions of the Kalam school (because of their consistency with Judaism), he disagrees with their methods and points out many perceived flaws in their arguments: "Maimonides exposes the weakness of these propositions, which he regards as founded not on a basis of positive facts, but on mere fiction ... Maimonides criticizes especially the tenth proposition of the Mutakallimīn, according to which everything that is conceivable by imagination is admissible: e.g., that the terrestrial globe should become the all-encompassing sphere, or that this sphere should become the terrestrial globe.

While Aristotle's view with respect to the eternity of the universe is rejected, Maimonides extensively borrows his proofs of the existence of God and his concepts such as the Prime Mover: "But as Maimonides recognizes the authority of Aristotle in all matters concerning the sublunary world, he proceeds to show that the Biblical account of the creation of the nether world is in perfect accord with Aristotelian views.

Subsequent lower levels reduce the immediacy between God and prophet, allowing prophecies through increasingly external and indirect factors such as angels and dreams.

After justifying this "crossing of the line" from hints to direct instruction, Maimonides explains the basic mystical concepts via the Biblical terms referring to Spheres, elements and Intelligences.

Indeed, says Maimonides, all existing evils, with the exception of some which have their origin in the laws of production and destruction and which are rather an expression of God's mercy, since by them the species are perpetuated, are created by men themselves.

However, he departs from traditional Rabbinic explanations in favour of a more physical/pragmatic approach by explaining the purpose of the commandments (especially of sacrifices) as intending to help wean the Israelites away from idolatry.

[9] Having culminated with the commandments, Maimonides concludes the work with the notion of the perfect and harmonious life, founded on the correct worship of God.

His views concerning angels, prophecy, and miracles—and especially his assertion that he would have had no difficulty in reconciling the biblical account of the creation with the doctrine of the eternity of the universe, had the Aristotelian proofs for it been conclusive[12]—provoked the indignation of his coreligionists.

[13] Likewise, some (most famously Rabbi Abraham ben David, known as the RaBad) objected to Maimonides' raising the notion of the incorporeality of God as a dogma, claiming that great and wise men of previous generations held a different view.

[14] In modern-day Jewish circles, controversies regarding Aristotelian thought are significantly less heated, and, over time, many of Maimonides' ideas have become authoritative.

[17] Several decades after Maimonides' death, a Muslim philosopher by the name of Muhammad ibn Abi-Bakr Al-Tabrizi wrote a commentary in Arabic on the first 25 propositions (out of 26) of Book Two, leaving out the last one, which states that the universe is eternal.

[citation needed] He wrote that his Guide was addressed to only a select and educated readership, and that he is proposing ideas that are deliberately concealed from the masses.

He writes in the introduction: No intelligent man will require and expect that on introducing any subject I shall completely exhaust it; or that on commencing the exposition of a figure I shall fully explain all its parts.

Thus we shall not be in opposition to the Divine Will (from which it is wrong to deviate) which has withheld from the multitude the truths required for the knowledge of God, according to the words, 'The secret of the Lord is with them that fear Him (Psalm 25:14)'[19]Marvin Fox comments on this: It is one of the mysteries of our intellectual history that these explicit statements of Maimonides, together with his other extensive instructions on how to read his book, have been so widely ignored.

The problem is to find a method for writing such book in a way that does not violate Jewish law while conveying its message successfully to those who are properly qualified.

[20]: 5 According to Fox, Maimonides carefully assembled the Guide "so as to protect people without a sound scientific and philosophical education from doctrines that they cannot understand and that would only harm them, while making the truths available to students with the proper personal and intellectual preparation.

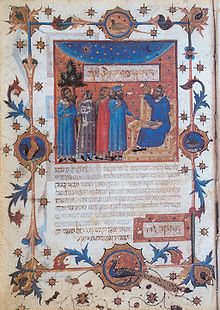

The first Hebrew translation (titled Moreh HaNevukhim) was written in 1204 by a contemporary of Maimonides, Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon in southern France.

A first complete translation in Latin (Rabbi Mossei Aegyptii Dux seu Director dubitantium aut perplexorum) was printed in Paris by Agostino Giustiniani/Augustinus Justinianus in 1520.

Publié Pour la première fois dans l'arabe original et accompagné d'une traduction française et notes des critiques littéraires et explicatives par S. Munk).

Despite the age of this publication it still has a good reputation, as Friedländer had solid command of Judeao-Arabic and remained particularly faithful to the literal text of Maimonides' work.

A new modern Hebrew translation has been written by Prof. Michael Schwartz, professor emeritus of Tel Aviv University's departments of Jewish philosophy and Arabic language and literature.

[31] In the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, England, there are at least fifteen incomplete copies and fragments of the original Arabic text, all described by Adolf Neubauer in his Catalogue of Hebrew Manuscripts.

[32] Hebrew translations of the Arabic texts, made by Samuel ibn Tibbon and Yehuda Alharizi, albeit independently of each other, abound in university and state libraries.