Morphogenesis

Some of the earliest ideas and mathematical descriptions on how physical processes and constraints affect biological growth, and hence natural patterns such as the spirals of phyllotaxis, were written by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson in his 1917 book On Growth and Form[2][3][note 1] and Alan Turing in his The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis (1952).

[6] Where Thompson explained animal body shapes as being created by varying rates of growth in different directions, for instance to create the spiral shell of a snail, Turing correctly predicted a mechanism of morphogenesis, the diffusion of two different chemical signals, one activating and one deactivating growth, to set up patterns of development, decades before the formation of such patterns was observed.

[7] The fuller understanding of the mechanisms involved in actual organisms required the discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953, and the development of molecular biology and biochemistry.

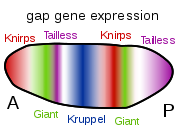

Morphogens are soluble molecules that can diffuse and carry signals that control cell differentiation via concentration gradients.

An important class of molecules involved in morphogenesis are transcription factor proteins that determine the fate of cells by interacting with DNA.

[8] At a tissue level, ignoring the means of control, morphogenesis arises because of cellular proliferation and motility.

Tissue separation can also occur via more dramatic cellular differentiation events during which epithelial cells become mesenchymal (see Epithelial–mesenchymal transition).

[11] In plants, cellular morphogenesis is tightly linked to the chemical composition and the mechanical properties of the cell wall.

Collagen, laminin, and fibronectin are major ECM molecules that are secreted and assembled into sheets, fibers, and gels.

Integrins bind extracellularly to fibronectin, laminin, or other ECM components, and intracellularly to microfilament-binding proteins α-actinin and talin to link the cytoskeleton with the outside.

Myosin-driven contractility in embryonic tissue morphogenesis is seen during the separation of germ layers in the model organisms Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila and zebrafish.

Maintaining an appropriate balance in the amounts of each of these proteins produced during viral infection appears to be critical for normal phage T4 morphogenesis.

As the rules' parameters are differentiable, they can be trained with gradient descent, a technique which has been highly optimized in recent years due to its use in machine learning.

A similar model to the one described above was subsequently extended to generate three-dimensional structures, and was demonstrated in the video game Minecraft, whose block-based nature made it particularly expedient for the simulation of 3D cellular automatons.