Azolla

[2] It is believed that this genus grew so prolifically during the Eocene (and thus absorbed such a large amount of carbon) that it triggered a global cooling event that has lasted to the present.

They form a symbiotic relationship with the cyanobacterium Anabaena azollae,[note 1] which lives outside the cells of its host and which fixes atmospheric nitrogen.

[15] The typical limiting factor on its growth is phosphorus; thus, an abundance of phosphorus—due for example to eutrophication or chemical runoff—often leads to Azolla blooms.

When rice paddies are flooded in the spring, they can be planted with Azolla, which then quickly multiplies to cover the water, suppressing weeds.

[19] Most species can produce large amounts of deoxyanthocyanins in response to various stresses,[20] including bright sunlight and extreme temperatures,[21][22] causing the water surface to appear to be covered with an intensely red carpet.

Herbivore feeding induces accumulation of deoxyanthocyanins and leads to a reduction in the proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the fronds, thus lowering their palatability and nutritive value.

[23] Azolla cannot survive winters with prolonged freezing, so is often grown as an ornamental plant at high latitudes where it cannot establish itself firmly enough to become a weed.

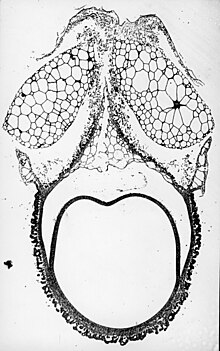

During the summer months, numerous spherical structures called sporocarps form on the undersides of the branches.

[26] The barbed glochidia on the male spore clusters cause them to cling to the female megaspores, thus facilitating fertilization.

In addition to its traditional cultivation as a bio-fertilizer for wetland paddies, Azolla is finding increasing use for sustainable production of livestock feed.

One FAO study describes how Azolla integrates into a tropical biomass agricultural system, reducing the need for food supplements.

[33] Previous studies attributed neurotoxin production to Anabaena flos-aquae species, which is also a type of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria.

By the end of the Ming dynasty in the early 17th century, Azolla's use as a green compost was documented in local records.

The proposal draws upon the hypothesized Azolla event that asserts that 55 million years ago, Azolla covered the Arctic – at the time a hot, tropical, freshwater environment – and then sank, permanently sequestering teratons of carbon that would otherwise have contributed to the planet's greenhouse effect.

This ended a warming event that reached 12–15 °C (22–27 °F) warmer than present-day averages, eventually causing the formation of ice sheets in Antarctica and the current "icehouse period".