Motte-and-bailey castle

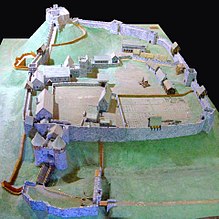

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade.

Relatively easy to build with unskilled labour, but still militarily formidable, these castles were built across northern Europe from the 10th century onwards, spreading from Normandy and Anjou in France, into the Holy Roman Empire, as well as the Low Countries it controlled, in the 11th century,[1] when these castles were popularized in the area that became the Netherlands.

By the end of the 13th century, the design was largely superseded by alternative forms of fortification, but the earthworks remain a prominent feature in many countries.

De Colmieu described how the nobles would build "a mound of earth as high as they can and dig a ditch about it as wide and deep as possible.

The space on top of the mound is enclosed by a palisade of very strong hewn logs, strengthened at intervals by as many towers as their means can provide.

The entrance to the fortress is by means of a bridge, which, rising from the outer side of the moat and supported on posts as it ascends, reaches to the top of the mound".

[16] Many wooden keeps were designed with bretèches, or brattices, small balconies that projected from the upper floors of the building, allowing defenders to cover the base of the fortification wall.

[18] Wooden structures on mottes could be protected by skins and hides to prevent their being easily set alight during a siege.

[16] The bailey was an enclosed courtyard overlooked by the high motte and surrounded by a wooden fence called a palisade and another ditch.

[19] The bailey would contain a wide number of buildings, including a hall, kitchens, a chapel, barracks, stores, stables, forges or workshops, and was the centre of the castle's economic activity.

[22] Wherever possible, nearby streams and rivers would be dammed or diverted, creating water-filled moats, artificial lakes and other forms of water defences.

[28] Regardless of the sequencing, artificial mottes had to be built by piling up earth; this work was undertaken by hand, using wooden shovels and hand-barrows, possibly with picks as well in the later periods.

[21] Where the local workforce had to be paid – such as at Clones in Ireland, built in 1211 using imported labourers – the costs would rise quickly, in this case reaching £20.

[35] Layers of turf could also be added to stabilise the motte as it was built up, or a core of stones placed as the heart of the structure to provide strength.

[39] A popular alternative was the ringwork castle, involving a palisade being built on top of a raised earth rampart, protected by a ditch.

[42] The motte-and-bailey castle is a particularly western and northern European phenomenon, most numerous in France and Britain, but also seen in Denmark, Germany, Southern Italy and occasionally beyond.

[50][nb 1] Finally, there may be a link between the local geography and the building of motte-and-bailey castles, which are usually built on low-lying areas, in many cases subject to regular flooding.

[51] Regardless of the reasons behind the initial popularity of the motte-and-bailey design, however, there is widespread agreement that the castles were first widely adopted in Normandy and Angevin territory in the 10th and 11th centuries.

[60] motte-and-bailey castle building substantially enhanced the prestige of local nobles, and it has been suggested that their early adoption was because they were a cheaper way of imitating the more prestigious Höhenburgen built on high ground, but this is usually regarded as unlikely.

[75] By the end of the medieval period, however, the terpen gave way to hege wieren, non-residential defensive towers, often on motte-like mounds, owned by the increasingly powerful nobles and landowners.

[75] On Zeeland the local lords had a high degree of independence during the 12th and 13th centuries, owing to the wider conflict for power between neighbouring Flanders and Friesland.

[80] Except for a handful of motte and bailey castles in Norway, built in the first half of the 11th century and including the royal residence in Oslo, the design did not play a role further north in Scandinavia.

In response, the Welsh princes and lords began to build their own castles, frequently motte-and-bailey designs, usually in wood.

[82] There are indications that this may have begun from 1111 onwards under Prince Cadwgan ap Bleddyn, with the first documentary evidence of a native Welsh castle being at Cymmer in 1116.

[85] David I encouraged Norman and French nobles to settle in Scotland, introducing a feudal mode of landholding and the use of castles as a way of controlling the contested lowlands.

[91] Unlike Wales, the indigenous Irish lords do not appear to have constructed their own castles in any significant number during the period.

In the late-12th century, the Normans invaded southern Italy and Sicily; although they had the technology to build more modern designs, in many cases wooden motte-and-bailey castles were built instead for reasons of speed.

At the end of the 12th century, the Welsh rulers began to build castles in stone, primarily in the principality of North Wales and usually along the higher peaks where mottes were unnecessary.

[109] By the 12th century, the castles in Western Germany began to thin in number, due to changes in land ownership, and various mottes were abandoned.

[111] In England, motte-and-bailey earthworks were put to various uses over later years; in some cases, mottes were turned into garden features in the 18th century, or reused as military defences during the Second World War.