Victorian fashion

Various movement in architecture, literature, and the decorative and visual arts as well as a changing perception of gender roles also influenced fashion.

By 1905, clothing was increasingly factory made and often sold in large, fixed-price department stores, spurring a new age of consumerism with the rising middle class who benefited from the industrial revolution.

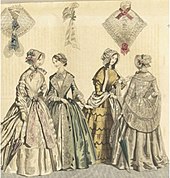

Upper-class women, who did not need to work, often wore a tightly laced corset over a bodice or chemisette, and paired them with a skirt adorned with numerous embroideries and trims; over layers of petticoats.

During the start of Queen Victoria's reign in 1837, the ideal shape of the Victorian woman was a long slim torso emphasised by wide hips.

Along with the bodice was a long skirt, featuring layers of horsehair petticoats[4] worn underneath to create fullness; while placing emphasis on the small waist.

In the 1840s, collapsed sleeves, low necklines, elongated V-shaped bodices, and fuller skirts characterised the dress styles of women.

In accordance with the heavily boned corset and seam lines on the bodice as well, the popular low and narrow waist was thus accentuated.

[5] As a result, the middle of the decade saw sleeves flaring out from the elbow into a funnel shape; requiring undersleeves to be worn in order to cover the lower arms.

Necklines of day dresses dropped even lower into a V-shape, causing a need to cover the bust area with a chemisette.

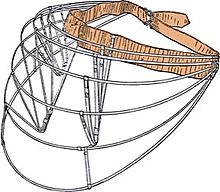

The purpose of the crinoline was to create an artificial hourglass silhouette by accentuating the hips, and fashioning an illusion of a small waist; along with the corset.

The cage crinoline was constructed by joining thin metal strips together to form a circular structure that could solely support the large width of the skirt.

[1] Although often ridiculed by journalists and cartoonists of the time as the crinoline swelled in size, this innovation freed women from the heavy weight of petticoats and was a much more hygienic option.

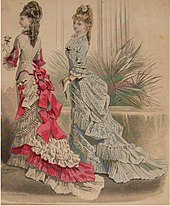

In order to emphasise the back, the train was gathered together to form soft folds and draperies[10] The trend for broad skirts slowly disappeared during the 1870s, as women started to prefer an even slimmer silhouette.

Others noted the growth in cycling and tennis as acceptable feminine pursuits that demanded a greater ease of movement in women's clothing.

[1] Still others argued that the growing popularity of tailored semi-masculine suits was simply a fashionable style, and indicated neither advanced views nor the need for practical clothes.

[7] Nonetheless, the diversification in options and adoption of what was considered menswear at that time coincided with growing power and social status of women towards the late-Victorian period.

Women thus adopted the style of the tailored jacket, which improved their posture and confidence, while reflecting the standards of early female liberation.

To enhance the style without distracting from it, hats were modest in size and design, straw and fabric bonnets being the popular choice.

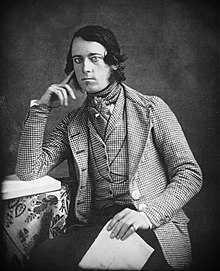

Shirts were made of linen or cotton with low collars, occasionally turned down, and were worn with wide cravats or neck ties.

Half-mourning was a transition period when black was replaced by acceptable colours such as lavender and mauve, possibly considered acceptable transition colours because of the tradition of Church of England (and Catholic) clergy wearing lavender or mauve stoles for funeral services, to represent the Passion of Christ.

"[17] Manners and Rules of Good Society, or, Solecisms to be Avoided (London, Frederick Warne & Co., 1887) gives clear instructions, such as the following:[18] The complexity of these etiquette rules extends to specific mourning periods and attire for siblings, step-parents, aunts and uncles distinguished by blood and by marriage, nieces, nephews, first and second cousins, children, infants, and "connections" (who were entitled to ordinary mourning for a period of "1–3 weeks, depending on level of intimacy").

[19] Women who mourned in black for longer periods were accorded great respect in public for their devotion to the departed, the most prominent example being Queen Victoria herself.

[20] Technological advancements not only influenced the economy but brought a major change in the fashion styles worn by men and women.

In 1850s there were more fashion technological advancements hence 1850s could rightly be called a revolution in the Victorian fashion industry such as the innovation of artificial cage crinoline that gave women an artificial hourglass silhouette this meant that women did not have to wear layers of petticoats anymore to achieve illusion of wide hips and it was also hygienic.

[23] Charles Frederick Worth, a prominent English designer, became popular amongst the upper class though its city of destiny always is Paris.

In 1855, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of Britain welcomed Napoleon III and Eugenie of France to a full state visit to England.

Later Queen Victoria also appointed Charles Frederick Worth as her dress maker and he became a prominent designer amongst the European upper class.

Charles Frederick Worth is known as the father of the haute couture as later the concept of labels were also invented in the late 19th century as custom, made to fit tailoring became mainstream.

This phenomenon was the result of the growing textile manufacturing sector, developing mass production processes, and increasing attempts to market fashion to men.

The piano leg story seems to have originated in the 1839 book, A Diary in America written by Captain Frederick Marryat, as a satirical comment on American prissiness.