Isabella Beeton

Beeton was working on an abridged version of her book, which was to be titled The Dictionary of Every-Day Cookery, when she died of puerperal fever in February 1865 at the age of 28.

Two of her biographers, Nancy Spain and Kathryn Hughes, posit the theory that Samuel had unknowingly contracted syphilis in a premarital liaison with a prostitute, and had unwittingly passed the disease on to his wife.

Several cookery writers, including Elizabeth David and Clarissa Dickson Wright, have criticised Beeton's work, particularly her use of other people's recipes.

[2][b] He died when Isabella was four years old,[c] and Elizabeth, pregnant and unable to cope with raising the children on her own while maintaining Benjamin's business, sent her two elder daughters to live with relatives.

His family had lived in Milk Street at the same time as the Maysons—Samuel's father still ran the Dolphin Tavern there—and Samuel's sisters had also attended the same Heidelberg school as Isabella.

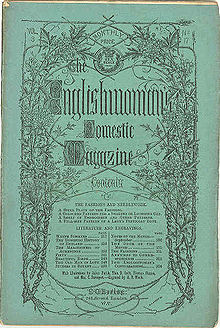

[26] A few weeks before the birth, Samuel persuaded his wife to contribute to The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, a publication that the food writers Mary Aylett and Olive Ordish consider was "designed to make women content with their lot inside the home, not to interest them in the world outside".

[38] In reproducing the recipes of others, Beeton was following the recommendation given to her by Henrietta English, a family friend, who wrote that "Cookery is a Science that is only learnt by Long Experience and years of study which of course you have not had.

[40][41] Beeton 's standardised layout used for the recipes also showed the approximate costs of each serving, the seasonality of the ingredients and the number of portions per dish.

[42] According to the twentieth-century British cookery writer Elizabeth David, one of the strengths of Beeton's writing was in the "clarity and details of her general instructions, her brisk comments, her no-nonsense asides".

[53][54] The Beetons decided to revamp The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, particularly the fashion column, which the historian Graham Nown describes as "a rather drab piece".

[55] They travelled to Paris in March 1860 to meet Adolphe Goubaud, the publisher of the French magazine Le Moniteur de la Mode.

The remainder provided advice on fashion, child care, animal husbandry, poisons, the management of servants, science, religion, first aid and the importance in the use of local and seasonal produce.

[73] Christopher Clausen, in his study of the British middle classes, sees that Beeton "reflected better than anyone else, and for a larger audience, the optimistic message that mid-Victorian England was filled with opportunities for those who were willing to learn how to take advantage of them".

[76] The critic for the Saturday Review wrote that "for a really valuable repertory of hints on all sorts of household matters, we recommend Mrs Beeton with few misgivings".

[78] Writing in The Morning Chronicle, an anonymous commentator opined that "Mrs Beeton has omitted nothing which tends to the comfort of housekeepers, or facilitates the many little troubles and cares that fall to the lot of every wife and mother.

His hubris in business affairs brought on financial difficulties and in early 1862 the couple had moved from their comfortable Pinner house to premises over their office.

Three days after Christmas his health worsened and he died on New Year's Eve 1862 at the age of three; his death certificate gave the cause as "suppressed scarlatina" and "laryngitis".

[81][j] In March 1863 Beeton found that she was pregnant again, and in April the couple moved to a house in Greenhithe, Kent; their son, who they named Orchart, was born on New Year's Eve 1863.

[9][l] When The Dictionary of Every-Day Cookery was published in the same year, Samuel added a tribute to his wife at the end: Her works speak for themselves; and, although taken from this world in the very height and strength, and in the early days of womanhood, she felt satisfaction—so great to all who strive with good intent and warm will—of knowing herself regarded with respect and gratitude.In May 1866, following a severe downturn in his financial fortunes, Samuel sold the rights to the Book of Household Management to Ward, Lock and Tyler (later Ward Lock & Co).

[92] In subsequent publications Ward Lock suppressed the details of the lives of the Beetons—especially the death of Isabella—in order to protect their investment by letting readers think she was still alive and creating recipes—what Hughes considers to be "intentional censorship".

[43] Since its initial publication the Book of Household Management has been issued in numerous hardback and paperback editions, translated into several languages and has never been out of print.

[97] Christopher Driver, the journalist and food critic, suggests that the "relative stagnation and want of refinement in the indigenous cooking of Britain between 1880 and 1930" may instead be explained by the "progressive debasement under successive editors, revises and enlargers".

[74] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term Mrs Beeton became used as a generic name for "an authority on cooking and domestic subjects" as early as 1891,[102][103] and Beetham opines that "'Mrs.

[43] In a review by Gavin Koh published in a 2009 issue of The BMJ, Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management was labelled a medical classic.

In Beeton's "attempt to educate the average reader about common medical complaints and their management", Koh argues, "she preceded the family health guides of today".

[112] The literary historian Kate Thomas sees Beeton as "a powerful force in the making of middle-class Victorian domesticity",[113] while the Oxford University Press, advertising an abridged edition of the Book of Household Management, considers Beeton's work a "founding text"[114] and "a force in shaping" the middle-class identity of the Victorian era.

[115] Within that identity, the historian Sarah Richardson sees that one of Beeton's achievements was the integration of different threads of domestic science into one volume, which "elevat[ed] the middle-class female housekeeper's role ... placing it in a broader and more public context".