Mud March (suffragists)

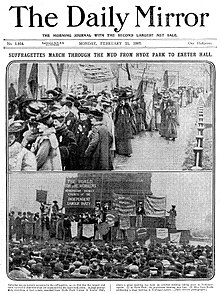

To maintain that momentum and to create support for a new suffrage bill in the House of Commons, the NUWSS and other groups organised the Mud March to coincide with the opening of Parliament.

Large peaceful public demonstrations, never previously attempted, became standard features of the suffrage campaign; on 21 June 1908 up to half a million people attended Women's Sunday, a WSPU rally in Hyde Park.

Although the NUWSS sought its objectives through constitutional means, such as petitions to parliament,[4] the WSPU organised open-air meetings and heckled politicians and chose jail over fines when it was prosecuted.

On 27 October 1906, in a letter to The Times, she wrote: The real responsibility for these sensational methods lies with the politicians, misnamed statesmen, who will not attend to a demand for justice until it is accompanied by some form of violence.

But I hope the more old-fashioned suffragists will stand by them; and I take this opportunity of staying that in my opinion, far from having injured the movement, they have done more during the last twelve months to bring it within the region of practical politics than we have been able to accomplish in the same number of years.

[27] Although the WSPU was not officially represented, many of its members attended, including Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Annie Kenney, Anne Cobden-Sanderson, Nellie Martel, Edith How-Martyn, Flora Drummond, Charlotte Despard and Gertrude Ansell.

[15] The procession was followed by a phalanx of carriages and motor cars, many of which carried flags bearing the letters "WS", red-and-white banners and bouquets of red and white flowers.

[31][32] Around 7,000 red-and-white rosettes had been provided for the marchers by the manufacturing company of Maud Arncliffe-Sennett, an actor and leader among the London Society for Women's Suffrage and the Actresses Franchise League.

When Hardie arrived from Exeter Hall, he expressed the hope that "no working man bring discredit on the class to which he belonged by denying to women those political rights which their fathers had won for them".

[26] The Times, an opponent of women's suffrage,[42] thought the event "remarkable as much for its representative character as for its size" and described the scenes and speeches in detail over 20 column inches.

[30] The Graphic, a pro-suffrage paper, published a series of illustrations sympathetic to the event except for one that showed a man holding aloft a pair of scissors "suggesting that demonstrating women should have their tongues cut out", according to Katherine Kelly in a study of how the suffrage movement was portrayed in the British press.

[42] In its leading article, The Observer warned that "the vital civic duty and natural function of women ... is the healthy propagation of race" and that the aim of the movement was "nothing less than complete sex emancipation".

The newspaper nevertheless welcomed that there had been "no attempts to bash policemen's helmets, to tear down the railings of the Park, to utter piercing war cries ..."[46] Likewise, The Daily News compared the event favourably to the actions of suffragettes: "Such a demonstration is far more likely to prove the reality of the demand for a vote than the practice of breaking up meetings held by Liberal Associations".

[50][51] On 26 February 1907 the Liberal MP for St Pancras North, Willoughby Dickinson, published the text of a bill proposing that women should have the vote subject to the same property qualification that applied to men.

[52] (On the day that the bill was published, the Cambridge Union passed by a small majority a motion "that this House would view with regret the extension of the franchise to women".

)[53] Although the bill received strong backing from the suffragist movement, it was viewed more equivocally in the House of Commons, some of whose members regarded it as giving more votes to the propertied classes but doing nothing for working women.

[39] In her 1988 study of the suffrage campaign, Tickner observes that "modest and uncertain as it was by subsequent standards, [the march] established the precedent of large-scale processions, carefully ordered and publicised, accompanied by banners, bands and the colours of the participant societies".

[62] The failure of Dickinson's bill brought about a change in the NUWSS's strategy; it began to intervene directly in by-elections, on behalf of the candidate of any party who would publicly support women's suffrage.

[64] During the NUWSS's Great Pilgrimage of April 1913, women marched from all over the country to London for a mass rally in Hyde Park, which fifty thousand attended.

[67] Full enfranchisement of all women over 21 came ten years later, when the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act of 1928 was passed by a Conservative government under Stanley Baldwin.

[69][70] It is not so much who is to mind the baby ... but a question concerning the fundamental idea of sex, and the effects physical, mental and economic, that any revolutionary change in the conditions of women's life must have on the vital civic duty and natural function of women—which is the healthy propagation of race. ...

The small section of women who desire the vote completely ignore the educational feature of the whole question, as they do the natural laws of physical force and the teachings of history about men and Government.